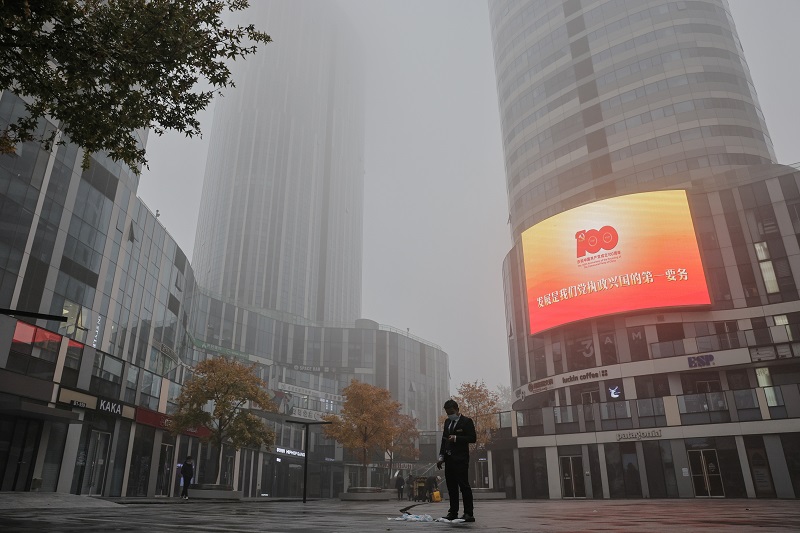

Freedom House concluded that China’s campaign of global repression and control is unprecedented in human history. But there are signs of pushback, as countries become aware of the dangers of embracing China.

London: China conducts the most sophisticated global and comprehensive campaign of transnational repression in the world, according to a new report by Freedom House, a US based human rights NGO. Every arm of the PRC government has been called upon to join in the work of influencing opinion, stifling free speech and controlling dissent within and beyond its borders. In a tally of direct physical attacks originating from China since 2014, according to the report there were at least 214 incidents in 36 different countries, ranging from abductions in Thailand to physical assaults in Canada. Even more frequent than these blatant attacks are the growing incidences of harassment and intimidation. Exiles and activists all over the world have reported threatening phone calls and cyber-attacks. Chinese students in the UK and Australia have reported being threatened and harassed if they criticise the PRC in any way.

As China’s global footprint expands, so does the way it in which the Communist Party tries to pressurise and control the overseas Chinese population and members of minority communities. How do they do this?

According to Freedom House, the sheer breadth and global scale of the CCP’s campaign of repression is unparalleled in human history. The Party targets a vast number groups, such as multiple ethnic and religious minorities, political dissidents, human rights activists, journalists, and former insiders accused of corruption. It then uses the full spectrum of repressive tactics: direct attacks on their targets, which may include rendition; co-opting other countries to detain and render exiles; and the use of digital threats, spyware and coercion by proxy. This process of surveillance, harassment and intimidation leaves many overseas Chinese and exile minorities feeling that the CCP is continuously watching them and constraining their ability to exercise basic rights, even when living in a foreign democracy. Freedom House claims that these tactics affect millions of Chinese and minority populations from China in at least 36 host countries across every inhabited continent.

Ethnic and religious groups numbering abroad in their thousands, such as the Uighurs, Tibetans and Falung Gong, are firmly in the sights of the CCP. Over the past year the list of targets has expanded to include Inner Mongolians and Hong Kongers residing outside the People’s Republic of China. But recently a new group of targets has also appeared, following Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption drive. These are the thousands of former Chinese officials now living abroad in the US and Europe and labelled as alleged embezzlers, who Xi’s security services are brazenly pursuing while defying other nation’s laws and borders with impunity. The targets are not murderers or drug lords, but Chinese public officials and businesspeople accused, justifiably or not, of financial crimes. Some of them have set up high-rolling lives overseas with lush mansions and millions in offshore accounts. Others are simply dissidents, whistle-blowers or relatively minor figures swept up in provincial conflicts, leading to the image of the Chinese government using the anti-corruption campaign within China and abroad for its political purposes.

The United States has become a major region of infiltration and there is mounting evidence that over the past seven years or so, Chinese fugitive hunters have stalked hundreds of people across the country in every state. Undercover repatriation teams have entered under false pretences, enlisted US-based accomplices and relentlessly hounded their targets. To “encourage” them to return to the motherland, authorities in China subject their relatives to harassment, jail, torture and other mistreatment, sometimes recording hostage-like videos to send to the US.

In countries such as Vietnam and Australia, Chinese agents have simply abducted their prey, whether the targets were dissidents or people accused of corruption. In the US, where such kidnappings are more difficult, the agents rely mainly on coercion, using proxies to apply pressure and leverage threats against the family. In 2018, Chinese state media claimed that 3,000 people had “returned or been repatriated” from 90 countries—so the system is working.

The build-up of vast numbers of Chinese cultural associations, diaspora groups, and even organised crime groups has given the CCP a simple avenue of influence among the huge population of Chinese citizens living abroad. Chinese law requires citizens to assist China’s all-powerful intelligence agencies, a mentality that now extends abroad into the diaspora, where systematic spying dates back decades. China’s spies from its intelligence agencies travel abroad to monitor troubling dissidents by infiltrating organisations, such as the Chinese Students and Scholars Associations that have been set up with government backing on most university campuses with many Chinese students. This provides them with suitable cover to carry out intelligence gathering and coercion.

On top of this, China’s well-developed technological prowess has given Beijing a toolbox of transnational repression, using such weapons as sophisticated hacking and phishing. The latest of these is WeChat, a messaging, social media, and financial services app that is ubiquitous among Chinese around the world, with more than 1.1 billion users. The CCP uses natural language processing and machine learning technology to watch everything on WeChat, and as many accounts are also connected to users’ bank accounts, everything about them can easily be tracked in real life. ‘WeChat is a prison that traps the minds of overseas Chinese people as if they have never left China’, said Wang Yaqiu, a China researcher at the New York-based Human Rights Watch.

China’s geopolitical and economic weight through the Belt and Road Initiative also allows it to assert unparalleled influence over a host of countries, giving it leverage that the CCP doesn’t hesitate to use against targets around the world. Chinese firms heavily involved in creating infrastructure in many countries keep quiet about the existence of their company’s Party organisations as well as its activities. In this covert way, Beijing’s influence is powerful enough to not only violate the rule of law, but also to reshape legal systems and international norms in its own interests. Take as an example the relentless political pressure that China’s economic weight has exerted on the world’s Muslim-majority nations. Pakistan screamed loudly about Salman Rushdie’s novels and Denmark’s cartoon drawings, but remained silent, refusing to say even a word in protest against China’s crimes in Xinjiang against the Muslim minority. Fear breads hypocrisy.

With so much activity in so many areas, it’s not surprising that Freedom House concluded that China’s campaign of global repression and control is unprecedented in human history. But there are signs of pushback, as countries become aware of the dangers of embracing China. Those which chose to accept the debt-diplomacy of BRI, the signature vanity project of Xi Jinping, will continue to be subject to the brutal influence of China for years to come, but regional players have recently been pursuing more coordinated actions so as to create a more stable balance of power.

Early this year, Australia cancelled two deals made between the state of Victoria and China. African countries are now more cautious about accepting Chinese money, having discovered that Chinese companies which carried out construction work on at least 186 sensitive government buildings in 35 African countries, had installed 14 “secure” telecommunications networks which potentially provides China with valuable intelligence. In February, the UK government revoked the broadcasting licence for China Global Television Network for gross bias and non-compliance. In addition to the US, eight countries have banned outright Huawei’s 5G technology because of security concerns.

On the macro-scale, in a direct response to China’s belligerence the EU this year released its Indo-Pacific strategy which aims for “regional stability, security, prosperity and regional development”, calling for the 27-nation grouping “to work together with its partners in the Indo-Pacific on these issues of common interest”. This belated response of the EU coincides with the resurrection of the Quad, which further illustrates that regional players are beginning to engage with each other more effectively. China has employed its entire might in trying to discredit this narrative in an unsuccessful attempt which only amplified its diplomatic failure. The lesson which Beijing finds hard to accept is that the more it pushes its pugnacious behaviour on regional states, the more pushback it faces. Today, China is left with only Russian support, while the rest of the world is moving on.

John Dobson is a former British diplomat, who also worked in UK Prime Minister John Major’s office between 1995 and 1998.