Slipping in the polls and outraised by a handful of rivals, Sanders is facing growing pressure from some of his allies, and within his own ranks, to adjust his strategy.

When Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., brought his presidential campaign to Pittsburgh earlier this year, he quietly added a poignant stop to his schedule: a visit to the Tree of Life synagogue, where 11 congregants were killed in an anti-Semitic shooting last fall.

But his appearance also came with explicit instructions to his campaign aides, according to two Democrats familiar with the conversation: They were not to tell the news media about his conversation with the rabbi there.

Some aides dissented, believing there was a graceful way to disclose the visit. But Sanders, the only Jewish candidate among the leading Democratic contenders, did not want the visit to be perceived as a publicity grab. His impulse illustrated a deeper challenge confronting his aides and supporters: After nearly four decades of running, and usually winning, iconoclastic campaigns on his own terms, he is deeply reluctant to change his approach.

Sanders has been unwilling to regularly talk about his personal history of growing up poor in a Brooklyn neighborhood full of Holocaust survivors, and until recently he resisted letting his campaign poll voters in Iowa, the first nominating state. He has largely defied his staff’s urging that he go on the offensive against Joe Biden, the Democratic front-runner.

But now, slipping in the polls and outraised by a handful of rivals, including a fellow progressive, Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, Sanders is facing growing pressure from some of his allies, and within his own ranks, to adjust his strategy.

“I do think he’s going to have to draw a contrast with the vice president,” said Rep. Ro Khanna, D-Calif., one of Sanders’ four campaign co-chairs, referring to Biden. He added that the 77-year-old Vermont senator should also “speak about his personal story.”

Voters, Khanna said, “have got to see that human side.”

In what is shaping up to be a volatile Democratic primary, Sanders retains significant strengths. He has more money on hand ($30 million) than any other candidate, and nearly all his donors can contribute again because they have yet to give the

maximum amount. He enjoys the unwavering devotion of his core base of voters, support that will not flag with the ups and downs of the campaign.

In a contest that could remain splintered after Iowa and New Hampshire, and in which candidates only need to garner 15% of the vote to earn delegates, that loyalty may prove critical to keeping Sanders in contention up to the convention.

Yet Sanders has struggled to expand his support in the early nominating states beyond those die-hard supporters. In Iowa, for example, he has fallen to fourth place in recent polling.

A Wall Street Journal/NBC News national poll released Thursday showed him tied for third, well behind Biden and Warren. And his advisers acknowledge that just under half of his supporters that they’ve identified from the 2016 Iowa caucuses, where he came within a point of defeating Hillary Clinton, have defected to other candidates.

Jeff Weaver, Sanders’ closest adviser, suggested in an interview that the campaign may make some modifications to re-energize his bid. “A smart campaign is always tweaking,” he said.

But he emphasized that there would be no wholesale changes, and disparaged the ways that some presidential hopefuls attempt to forge a personal connection with voters.

“Let’s be clear about this point: If somebody wants a candidate who is going to make health care a right, raise wages, deal with climate change, deal with immigration reform and criminal justice reform, Bernie Sanders is your candidate,” said Weaver. “If you want somebody who’s going to talk about their cooking, their dog, their wardrobe, travel habits, or favorite books, Bernie Sanders is not your candidate.”

“This is not a popularity contest or a find-a-friend contest,” he said.

While Warren is making incursions with some of Sanders’ progressive backers, campaign aides insist that they view Biden as a far more significant threat because of his support from some of the working-class voters who voted for Sanders in 2016.

Yet Sanders’ campaign faces a conundrum in how to run against Warren. Though aides grumble that she has claimed some of Sanders’ long-held, anti-big business stances, they all but rule out the prospect of aggressively confronting someone their candidate considers a personal friend.

“I do not see a situation at all where Bernie Sanders allows the campaign to do that,” Ari Rabin-Havt, the campaign’s chief of staff, said about attacking Warren. “That’s not who he is and that’s not how he feels about Elizabeth Warren.”

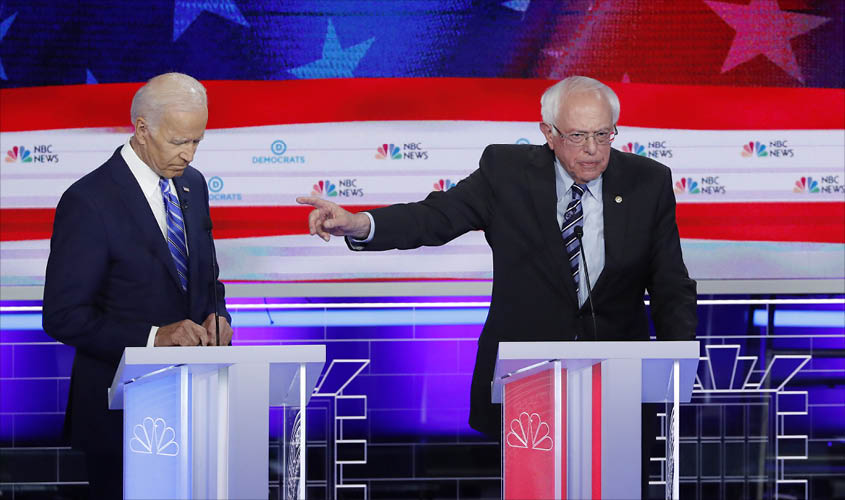

It is a different story with Biden. Sanders’ advisers had hoped he would challenge the former vice president at last month’s debate, according to multiple Democrats familiar with their conversations. After choosing not to, Sanders found himself largely left out of the post-debate conversation, which was dominated by Sen. Kamala Harris’ criticism of Biden’s past opposition to busing.

Weaver expressed hope that his candidate would take on Biden over his support for free trade pacts that are highly unpopular among blue-collar voters in the Midwest.

“Joe Biden has some serious issues when it comes to the trade policies he has supported and reaffirmed his support for,” Weaver said.

However, even Sanders’ aides acknowledge that they would like to see him talk more about his post-World War II childhood in Brooklyn, where he was surrounded by Jewish immigrants who bore the tattoos Nazis had branded them with. In a campaign in which issues of race and discrimination have been central, and in which the inhumane treatment of migrants has become a partisan flash point, the senator’s advisers believe he has something to contribute to that discussion and that many voters today are open to a Jewish president.

Sanders highlighted his biography at the outset of this campaign, but since has done so only sporadically. While he can be persuaded to share small details of his story in interviews or prepared speeches, on the stump he invariably reverts to what is essentially a compilation of his greatest hits: jeremiads against the greed of plutocrats and paeans for universal health care.

In a primary with so many candidates making their personal stories central — Harris’ recounting her childhood experiences with busing; Pete Buttigieg talking about his sexuality; Warren citing her modest roots — it is even more striking that Sanders is reluctant to use autobiography as another tool to stand out in the field.

And unlike during the 2016 campaign, when Democratic voters had only to choose between him and the establishment-aligned Hillary Clinton, progressives now can select from a wealth of candidates singing from the same populist hymnal.

“In some ways, I think that he has been so extremely successful that his platform has become the norm,” said Brent Welder, a Sanders supporter who ran for Congress in Kansas last year.

Which is to say he is at risk of being a victim of his own success. And that, perhaps, highlights the fundamental tension of Sanders’ candidacy: It may prove difficult for him to expand his support without broadening his message, yet what draws many of his fervent supporters in the first place is the constancy of his appeals.

“Bernie Sanders always runs his own campaign — it may be unscripted, but it’s focused on his issues,” said Mark Longabaugh, who was one of Sanders’ top advisers in 2016. Longabaugh and his partners abruptly left the 2020 team shortly after its formation because they concluded the senator and his wife, Jane, were unwilling to cede any real control.

Weaver said the senator was open to advice, but acknowledged that he at times goes his own way.

“He accepts some of it, he doesn’t accept others of it,” he said. “But he always wants ideas.”

Though he can be gruff on the campaign trail and prefers holding big rallies, Sanders has begun in recent weeks to hold smaller events like ice cream socials and has even acquiesced to taking photos with supporters who line up to see him.

Still, the angst among some of Sanders’ own supporters has been building.

While he has sought to elevate matters of racial justice more in this campaign than he did in 2016, his overriding focus remains economic equality. At times, that message can feel discordant from the energy of the Democratic Party at a moment when President Donald Trump has helped elevate issues of race, gender and sexuality.

In May, during a sweep through the South just days after Alabama passed a law effectively banning abortion, Sanders responded to a national outcry on the left by devoting only a small

portion of his speaking time to addressing the measure at a series of town halls and rallies. Some allies said they found that response puzzling.

Later that month, he returned to Vermont to deliver a speech at the state capitol in Montpelier. It was a homecoming event that his campaign billed as an opportunity to amplify his long political record in the state and accentuate a topic his aides have been eager to highlight: his history of winning difficult races and defeating Republicans.

But Sanders made scant mention of his accomplishments. The only real deviation from his usual stump speech was a fresh attack on the media that stemmed from a story in The New York Times about his left-wing foreign policy activism as mayor of Burlington, Vermont, in the 1980s.

Then, last month, Sanders planned another speech aimed at reframing the race: an address in Washington meant to defuse attacks on the democratic socialism he espouses, by tracing his agenda back to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Some of his allies expressed skepticism about the wisdom of holding up a president who has been dead for nearly 75 years as a point of comparison — a move akin to George McGovern linking himself to the populism of William Jennings Bryan in 1972 — but Sanders would not be denied. He has since

introduced a sticker inspired by Roosevelt, and his

campaign quotes the former president on a new webpage that lists what Sanders is calling “anti-endorsements” from tycoons whose contempt he relishes in the same fashion of his political role model.

If it all rings familiar, well, that’s just fine by Sanders.

After the first debate, when a chorus of critics panned Sanders for reciting his most familiar themes and doing little to distinguish himself, he wryly acknowledged that “they’re probably right.”

“It’s never made sense to me that a few people have incredible wealth and power while most have none,” he wrote on Twitter. “Should we ever achieve justice, I promise I’ll write some new speeches.”

© 2019 The New York Times