India would be able to explore the sources of water and helium-3 and harness the potential of Moon’s surface.

The successful launch of Chandrayaan-2 by Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has led India to become a part of an exclusive club of countries that have already gone for lunar probes. The launch has reflected India’s space technology prowess and also boosted the overall confidence, especially in defining the future trajectory of its strategic aspirations in Outer Space. The way things are unfolding in Outer Space, the days are not that far when human settlements in Outer Space would become a reality. India wants to maintain the pace of development in Outer Space and underscore a point that it would like to be seen as a major space power, both in the civilian as well as in the military domain.

It is certainly interesting times for the geopolitics of Outer Space both from the point of view of advances in space technology, as well as the distinct behavioural patterns of those space faring nations that have been competing for both information dominance and information assurance in the wider spectrum. By 2024, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is planning to take astronauts to the Moon. The way things are evolving, Elon Musk’s Space X will be successful in colonising Mars in the next 10 to 15 years.

India’s keenness to explore the universe has grown over the years. The lunar mission has been a byproduct of its consistent efforts and its long-term vision. The mission has consisted of three modules—an orbiter, a lander named Vikram and a six-wheeled rover named Pragyan. Chandrayaan-2, after its successful launch has been orbiting the Moon and will perform the objectives of remote sensing the Moon. The whole exercise will help collect scientific information on lunar topography, mineralogy, lunar exosphere, different types of elements and signatures of hydroxyl and water ice. This launch was the second one after Chandrayaan 1, which was launched in 2008.

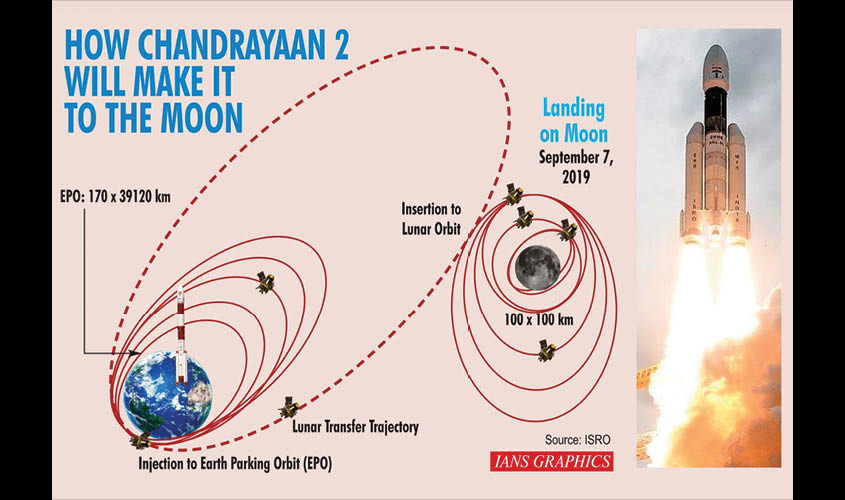

Despite the fact that India’s space agency has made remarkable progress in every front, the West and the United States have started drawing comparisons. They claim that Chandrayaan-2 mission may now be on its way to the Moon, but it has a slow journey ahead; they highlight that India’s spacecraft, called the Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV) Mark III, has less power than the Saturn V rockets that had driven NASA’s Apollo program. The Chandrayaan-2 mission will take a total of seven weeks to reach the Moon.

The parameters set for the spacecraft success of Chandrayaan-2 are being met in a planned manner. The orbit of Chandrayaan-2 around the Earth was raised for a fourth time to reach a highly elliptical orbit of 277×89,472 km on Friday. The on-board propulsion system was fired for 646 seconds as specified. The propulsion systems have to be fired once more on 6 August to increase the apogee or the point on the orbit farthest from the earth.

Six manoeuvres had been planned in the 23-day duration that Chandrayaan-2 would spend going around the Earth—one to increase the perigee or the point on the orbit closest to the Earth and five others to the apogee. The spacecraft will be injected in a translunar orbit (orbit between Earth and Moon) on 14 August. The spacecraft is scheduled to reach a lunar orbit on 20 August. The scientists at ISRO have been recalculating the orbit every hour and there is round-the-clock simulation to plan for the next move to ensure the spacecraft is on the right track. In this case, the orbit of the spacecraft can be adjusted if needed. It is unlike a launch vehicle, which one cannot guide once it is launched.

The lander-rover will be separated and move to a 100×30 km orbit. During separation, the optical high resolution camera on-board will be turned on to scout for a suitable landing site in the Lunar South Pole. The images taken will be transmitted to Earth and processed, after which the landing site map will be uploaded to the lander-rover before its powered descent to the Moon.

When the Vikram lander lands after completing all the assigned roles, it will land near the Moon’s South Pole, which happens to be an area of greater interest to scientists and explorers because of its stash of water ice in permanently shaded craters. There are a number of payloads on board and it is expected that both the lander and its companion rover will do the mapping and also analyse this water ice.

It must be emphasised here that if Chandrayaan-2’s flight and landing gets completed then India will become the first country to reach the Moon’s South Pole and will be the fourth country to successfully land softly on the Moon after the formerly Soviet Union, United States and China.

India does have one robotic Moon mission, the successful Chandrayaan-1, which was launched in October 2008 and operated through August 2009. Chandrayaan-1 consisted of an orbiter and an impactor, which slammed hard into the Lunar South Pole in November 2008. The evidence of having water ice on the Moon was seen through this exercise.

Chandrayaan-2 mission is different. It will settle into a circular orbit above the Moon’s surface. Eventually, the orbiter will deploy the lander-rover duo, which will touch down south of the lunar equator. The Chandrayaan-2 lander is named Vikram after Vikram Sarabhai, the father of the Indian space programme. The rover, called Pragyan will roll down from Vikram onto the lunar surface. The six-wheeled solar powered Pragyan will be able to travel up to 500 metres on the lunar surface. It seems the rover will communicate only with the lander, which will be capable of beaming information both to the Chandrayaan-2 orbiter and directly to the Indian Deep Space Network on Earth.

It must be pointed out here that all the three vehicles are completely packed with scientific instruments. The orbiter is carrying eight scientific instruments including multiple cameras and spectrometers. Vikram and Pragyan both are outfitted with four and two instruments respectively. The most encouraging part of this great mission has been that all of these payloads were developed by Indian scientists, except for one which is called the Laser Retroreflector Array (LRA). It must be mentioned here that the LRA is designed to help researchers pinpoint the location of a spacecraft on the lunar surface and calculate the distance from Earth to the Moon technically.

The success of Chandrayaan-2 will be vital for making improvements in the overall understanding of the Moon. The expected discoveries will benefit India and overall humanity. How lunar expeditions will be approached in the years to come is being redefined by such a highly ambitious mission. India, obviously, is not going to be alone in eyeing the Moon’s resource rich South Polar region. NASA has already unveiled its plans to land astronauts there in 2024 and build up a long-term sustainable presence on and around the Moon in the foreseeable future. India has also been contemplating the next steps in the form of Chandrayaan-3, which would bring soil and rock samples back from the Lunar South Pole. In this regard, ISRO has initiated dialogue with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) recently. It will be a joint lunar polar exploration mission. India is already working on “Gaganyaan”, which has been scheduled for 2022.

Though the United States was the first country to land humans on the Moon, technically the astronauts on that Apollo mission did not see what India’s Chandrayaan-1 un-crewed spacecraft found in 2008—evidence of water in the Moon’s craters. The evidence of water has enhanced the strategic importance of the Moon as a platform for space exploration. It seems helium-3 is also in abundance on the Moon’s surface. It is an energy producing isotope, which could power future fusion rockets. India, through Chandrayaan-2 mission, would be able to explore the sources of water and helium-3 and harness the potential of Moon’s surface. The 21st century will see a newer type of geopolitics in Outer Space where a country like India will emerge as one of the major leaders.

Dr Arvind Kumar is Professor of Geopolitics and International Relations, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal.