Sir Richard Needham, a veteran of British politics, writes about his efforts to retrace his family’s past in India, and his high-velocity campaign to improve business ties between the two countries.

India entered my life early. My Grenadier bachelor godfather Colonel David Beaumont-Nesbitt had spent several years in the 1930s attached to the Indian Army and fallen in love with everything Indian, especially the food. He would change into his silk dressing gown, light up the jos sticks and start stirring away. Curries became and remain the dishes I die for. He read me The Jungle Book, Kim, Just So Stories and “Riki-Tikki-Tavi”. I adored them. Unfortunately, when I was 21, he was killed in a car crash. Except for making a very great friend, Bhaichand Patel, at Law School, India disappeared from my life for 25 years.

In 1992, I became Minister of Trade and Michael Heseltine’s Deputy. I determined on a major government initiative to promote closer commercial relations throughout India by strengthening and financing the Indo-British Partnership. Hearing about this, my first cousin, Robin Needham, got in touch. Every generation of Needhams contains a “saint”. Robin was the one in mine. He was tragically drowned in the great Thailand tsunami of 2004. He dedicated his life to the charitable sector. He lived for three decades on the sub-continent, ending up as Director of Care in Nepal. He had spent several years in Calcutta and Bangladesh where he adopted two little girls.

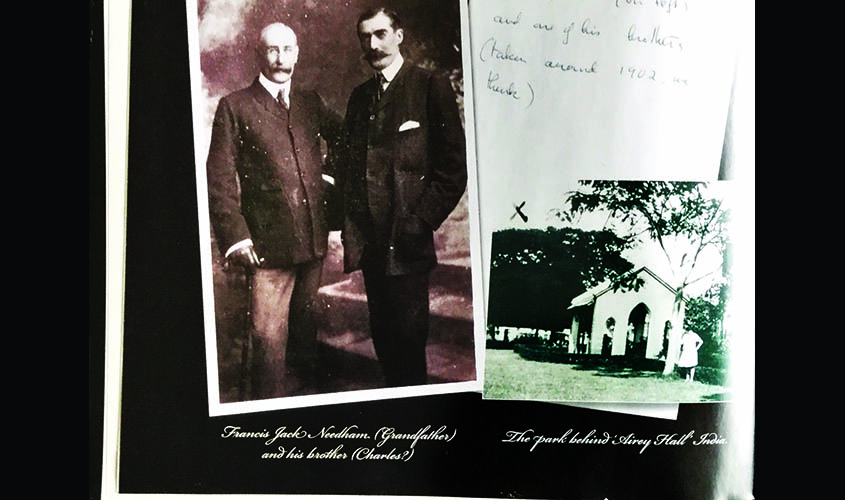

Robin told me that while in Calcutta, he had found several Needham graves in the huge ex-patriot local cemetery. There were rumours of a tribe of Indian Needhams somewhere to the north but the trail had gone cold. Perhaps in my new exalted position I could pick it up. I asked my private secretary, Rozmin Llada, whose family originally came from Gujarat, to help. She contacted the High Commissioner in Dehli. After several months, an Indian businessman phoned Rozmin and said that there was a tribe of Needham in Shillong in Assam. They were the descendants of one Francis Jack Needham. Jack Needham turned out to be a very remarkable man. Born in 1842 the eldest son of Francis Henry Needham, third son of Black Jack, second Earl of Kilmorey, he had gone off to Calcutta in the mid 1870s where he had joined the Bangal Police Force. In 1888 he was made Assistant Political Officer and sent off to control the wild tribes of the North East. He was to spend the rest of his days disappearing for weeks at a time with a handful of men, taming the local population and exploring the jungle.

After several years of learning the local languages and looking in vain for the source of the Bramaputra, he became a distinguished botanist and settled down with a local Assamese girl, called Mary, by whom he had eight children. He stayed there for the rest of his days, dying in 1924, a Fellow of the Royal Society and a Companion of the Indian Empire. His descendants meanwhile had fanned out across the globe.

It was obvious to me as Trade Minister that India was on the move and we needed to find ways of exploiting and building on a long and sometimes bitter path which had left our relationship uneasy and often fraught. The government , particularly a Tory one, had to show it took India and its opportunities seriously. We needed to avoid being patronising, to admit our imperial transgression, to welcome and encourage non-resident Indians in Britain and their families, to build on our long commercial and industrial ties, to be humble about our past and to flatter them how we needed them for our future as friends and investors.

To kick off this new initiative, we strengthened the India-British partnership and arranged a trade mission to Bombay where the star attraction was HMY Brittania. The High Commissioner, Sir Nicholas Fenn, was in charge. He was a nervous man who unfortunately used to go blind as soon as it began to get dark. We were invited to attend a reception run by the British Council for graduates and their parents at the University of Bombay outside the Rajabai Tower—a wonderful piece of late Victorian architecture, designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott and modelled on Big Ben. I asked Sir Nicholas whether I was expected to make a speech. Absolutely not, he was adamant. The Vice Chancellor’s oration reminded the visiting delegation of all the wickedness of British rule, not least because the tower and the adjoining library were falling to bits. Sir Gilbert had shipped all the drawings and materials out from England with a mecano instruction booklet on how to put it all together. Unfortunately, this did not include ways in which to make and repair stained glass windows. Most of these had now collapsed and the pigeons were inside the library rather than outside. The Vice Chancellor then invited me to address the 400 or so audience and tell them how we could redress this failure! I rose and responded. Never before had I been given the chance to deliver a speech which had not been drafted by civil servants, especially when it came to the spending of money. However, I had no draft, so I was free to say what I liked. I agreed with every word of the Vice Chancellor. We had behaved disgracefully. I would pledge the Government to train up young Indians at York Minster cathedral in the replacing and repairing of stained glass windows.

There were cheers. The High Commissioner sat pale and trembling. I have no budget, you can’t do this, this is monstrous. “You will have to pay for it yourself,” he fumed. “Well, I have just done it and I won’t pay for it myself.” It took four years for the British Council to find some funds, supported by my own endeavours. Now the not so young Indians are at York Minster repairing our windows as we have run out of stained glass craftsmen.

Encouraged by our success in Bombay, the next mission was more ambitious and involved renting a Concord for a week. A hundred business men were selected to cover four cities: Dehli, Calcutta, Madras and Bombay.

Many of the businessmen were large and the seats were narrow. Because we were flying overland for most of the way we had to travel subsonic. It took around six hours to reach Jeddah by which time tempers were getting frayed and we had consumed a combined total of 166 bottles of champagne and white wine. However, we did have the thrill of crossing the Bay of Bengal at mach 1.2.

The Indian end of the visit was organised by the CII (Confederation of Indian Industry). The CII was chaired by Jamjed Irani, one of the most senior directors of Tata and the most wonderfully relaxed and charming man. He took me aside after the first day and asked me to solve a dilemma he was wrestling with. He found it very difficult to get on with the Japanese. What was the problem? Was it that he could not get their names right? They all sounded the same! No I told him. The problem was more complicated. When the Japanese first arrive, the plane door opens and in rushes a blast of heat, followed by dust and some smells that are new to Japanese nostrils. At the bottom of the gangway they are greeted by large gentlemen with beards wearing night dresses and carrying garlands, who proceed to embrace them. By and large Japanese do not like facial hair and are not partial to being kissed by bearded men smelling of garlic.

After a lot of shouting and yelling they are bundled into waiting, sometimes airconditionless cars and whisked off through chaotic traffic for lunch or dinner. The Japanese are not on balance overly keen on hot curries, find Indian-English hard to follow. They finally lose interest in doing deals when having to spend the next two days on the khazi. “Ah, I see,” he said. Two years later he was presented with an Honourary KBE by the Queen and I happened to be at his inauguration. He said to the Queen, “Richard Needham has done more for Anglo-Indian relations than any former Minister.” The Queen looked at me and paused. “Really?” she said and moved on to my neighbour.

We went to Calcutta, the capital before Dehli, and met with the communist Chief Minister, Joyti Basu, a shrewd politician who did not make life easier for himself or his people by wanting to nationalise everything. The next stop was Madras to call on Madam Jayalalitaha, a famous former south Indian film star. She was covered in solid gold bangles and bracelets which tinkled whenever she moved. She told us of all the opportunities we could profit from on the back of her new low tax development zones, although of course, “we look at everything on a case by case basis”.

Swraj Paul, later Lord Paul, who it was alleged had been Mrs Indira Ghandi’s bag carrier, blurted out, ‘‘Surely suitcase by suitcase basis.’ This brought matters to a premature close.

I arranged to bring my three distant cousins from Assam down to Calcutta. Two of them were teachers in a Primary School and the other, the caretaker. There was no obvious evidence of my distant Needham relative, except for their sense of humour and their love of playing whist. They were Khasis which meant they followed a matrilineal tradition. So, the Needham connection had become a little hazy. They had never flown anywhere before but a trip round the bay in Concord singularly failed to faze them. They were very British Indian and I have been trying ever since to get them over to visit their original Irish roots but Concord seems to have satisfied any further desire to travel.

Post-Brexit, the India connection is perhaps our most important relationship outside the USA. The Indian community is one of the most, if not the most dynamic, successful and entrepreneurial. We must welcome and support them, particularly the students. One of the most encouraging trends in the Tory party is the increasing number of Indian descended MPs. It cannot now be beyond the realm of possibilities that in the not too distant future we might have a Prime Minister of Indian descent.

Sir Richard Needham is a former Minister of Trade in John Major’s Government and former Under Secretary of State for Northern Ireland