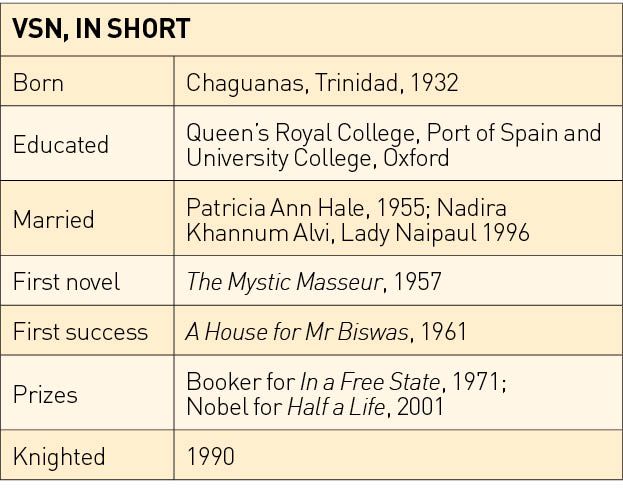

Earlier this year, a few weeks before his death on 11 August at the age of 85, Nobel Laureate V.S. Naipaul spoke to Ravi Kumar Kandamath about his life and love of letters.

RKK: Sir Vidia, have you ever felt you ought to have become something else other than being a writer? Have people close to you told you that your particular gifts could have been better used in another way?

VSN: Oh, please! Kumar Saheb! Call me Vidia! If I was bothered by what others do particularly, I wouldn’t have been a writer.

RKK: What prompted you to be one?

VSN: I wanted to be very famous. I also wanted to be a writer—to be famous for writing. The absurdity about the ambition was that at the time I had no idea what I was going to write about. The ambition came long before the material. Shyam Benegal once told me that he knew he wanted to make films from the age of six. I wasn’t as prodigal as he—I wanted to be a writer by the age of ten.

RKK: You caught him up in four years. And then?

VSN: Having gone to Oxford on a colonial government scholarship, which guaranteed to see you through any profession you wanted, instead of learning a profession, I chose this banality of English—a worthless degree, it has no value at all. I wanted to escape Trinidad. I was oppressed by the pettiness of colonial life and by the intense filial disputes in Hindu families in which people were judged and condemned on moral grounds. It was not a generous society—neither the colonial world nor the Hindu world. I had a vision that in the larger world people would be appreciated for what they were—people would be found interesting for what they were. And miraculously, the books began to appear.

RKK: Miraculously? That reminds me of Nirad Chandra Chaudhuri’s assertions that he was some kind of an oracle… What advice would you give would-be writers?

VSN: Nirad Chaudhuri was a clown!

RKK: He, on the other hand, thought you didn’t really understand India.

VSN: Being a writer for 60 years—you ought to trust me—that it involves a daily dose of life’s travails, disappointments and impediments.

One mustn’t be bowled over by any of that. One could even use one’s daily experiences as material for the woRKK as I have done.

RKK: You famously remaRKKed that the fatwa against Salman Rushdie was an extreme form of literary criticism. I know you—like me—follow India closely, on a daily basis. What are your comments on a similar mentality spreading in India? I am not being anti-Hindutva but referring to mindless incidents such as the attack on Sir Ross Masood’s library—to quote a recent example.

VSN: That was just cricket! The form that cricket takes in the sub-continent. (The mob attack on the library occurred shortly after a cricket match when India lost to Pakistan.)

RKK: Ha! But you have always been in favour of the revivalists!

VSN: Ravi, dangerous or not, Hindutva is a necessary “counteractive” in history and it will continue remaining to be so.

RKK: All your books have a sense of estrangement from surroundings and your life history has involved many moves sometimes more than half way across the globe. Trinidad, Oxford, London, India, Wiltshire… Where do you feel most at home?

VSN: In my books.

RKK: There is something that I really would like to ask. Forgive me if it offends you. I’m not a great admirer of fiction. You can see why John Julius (writer and broadcaster The Rt Hon Viscount Norwich, CVO, a mutual friend of VSN and Kandamath who writes under the pen-name John Julius Norwich) and I have had some great moments of agreement. I’ve only read your travel books and its treatment of the Indian landscape reminded one of Col Malgonkar’s (Lt Col ManoharMalgonkar, 1913-2010, Indian author whose The Princes, 1963, is considered a masterpiece in the West). Was he an influence? What I really would like to ask is, wasn’t there a time, not so long ago—I think when you were awarded the Nobel—that you thought you were finished with fiction?

VSN: I have immensely enjoyed parts of Manohar Malgonkar. He wrote for the few. That’s topic for a full day’s discussion. Regarding fiction—there was nothing for me, or in fact for any other novelist, left to say. Every subject had been touched upon.

RKK: You are right, the Colonel (Malgonkar) was writing from a different place. But you still wrote. Kept writing…?

VSN: The publishers pushed. They said you are saying fiction is over because you can’t write any more. They were provoking me and I was happy to be provoked. But making a book is such a big enterprise: inspiration, a great deal of illuminations. A whole life’s experience to deal with. And it colours every single word you write.

RKK: What’s your method?

VSN: I like to “fix scenes” in my books. “Very bright pictures.” People can never remember long descriptions. Just one or two images. But you have to choose them very carefully. That has always come naturally to me, of course! I am always thinking about the book. You are writing to write a book: to satisfy that need, to make a living, to leave a fair record behind, to alter what you think is incomplete and make it good.

RKK: Will you ever stop?

VSN: I think it will happen and I think it will be extremely painful. Without writing, everything will become insipid. Reading would have no point, because a writer reads with a purpose.

RKK: Coming to my world of public affairs, despite all your training, I think you are a classic product of a “Hindu education”. By that I mean how the Hindu mind was meant to be trained or gets trained by family conditioning. By that I mean a strong and clear-cut idea on what is essentially right and what is wrong. Although you broke away from all that in Trinidad, that never left you. You have never shiRKKed from criticising. Such formidable victims of scorn include not just the ones considered great literary men (for VSN didn’t include women in that world), E.M. Forster, Nirad C. Chaudhuri, Anthony Powell, even Dickens I believe, but also “that man” Edward Said, “pirate” Tony Blair and our “world leaders” of the time.

VSN: We are never isolated from the troubles of the world and we must deal with them accordingly.We must hate oppression but fear the oppressed as well. The liberal side has some strange explanations (on behalf of the oppressed). But Britain’s issues now—as you will know—are always highly subtle and complex. (Refers to Brexit and the EU; Naipaul was a Remainer at heart.)

RKK: What do we do about terrorism?

VSN: The response to this “rejoicing from people’s death” is bad and must stop or be stopped. There are certain countries that foment it and they should probably be destroyed.

RKK: Saudi, Iran? You don’t mean Pakistan, surely. (Lady Naipaul is Pakistani.)

VSN: We know that. It’s only us who can deal with that matter (regarding Pakistan).

Iraq is an obvious example of a “wrong war”. Look at the by-products. What we have to deal with in Britain: In this country, it’s become a kind of racket, this multiculturalism. A man can’t say, “I want the country, I want the laws and protection, but I want to live in my own way.”

RKK: I think we are running out of time. It’s almost time to leave. What would your parting message be? If you would want to tell me one thing you wished you knew when you began life?

VSN: I grew up with the idea that it is important to look inwards and not always define an external enemy. We must examine ourselves—our own weaknesses.

I still believe that. And for me, writing is the only noble calling. It is noble because it deals with the truth. Of course, there are many who write only to make a living.

You have to look for ways of dealing with your experience. You have to understand it and you have to understand the world. Writing is a constant striving after a deeper understanding. That is pretty noble.

* V.S. Naipaul (1932-2018) won the 2001 Nobel Prize for Literature and wrote more than 30 books over six decades.

* Ravi Kandamath is a public-affairs consultant and conciliator based in London. Kandamath serves on the board of the London School of Wellbeing, which includes, amongst its offerings, a course of holistic psychotherapy for writers. aRKKassociatesuk@gmail.com

© RAVI KUMAR PILLAI KANDAMATH 2018