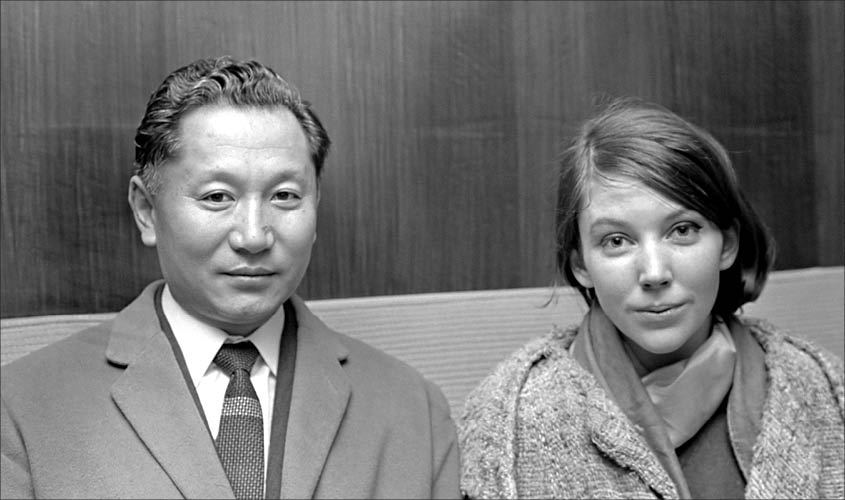

The king’s American wife, Hope Cooke did very little to change the perception of her being a CIA agent. She also argued that Darjeeling should be returned to Sikkim.

Long before London-based journalist Andrew Duff wrote Sikkim: Requiem for a Himalayan Kingdom in 2015, Sunanda K. Datta-Ray’s Smash and Grab: The Annexation of Sikkim was my primer on what became India’s 22nd state in 1975. The book, originally published in 1984 and later reprinted in 2013, attempted to shatter the long-held perception that Sikkim’s merger with India was all smooth and hunky-dory.

Reading Datta-Ray, a sense of guilt and solecism emerges. It makes us believe that democratic India did to Sikkim in the 1970s what Communist China committed in Tibet in the 1950s—smash and grab. The Indian forces took over the kingdom ruled by a “benign” and “benevolent” monarch, Chogyal Palden Thondup Namgyal, who—much like the reader of the book—was utterly bewildered by Delhi’s move. “They’ve got everything already! What more can India possibly want?” the king would say. Under the 1950 treaty, after all, India controlled Sikkim’s foreign relations, defence and communications, and could also intervene if law and order were threatened or if there was gross internal maladministration.

But was Thondup as naïve, benign and benevolent as he had been made out to be? Was the merger such a travesty of justice, fair play and, worse, common sense, as Datta-Ray wanted us to believe? If G.B.S. Sidhu’s just released Sikkim: Dawn of Democracy is anything to go by, these assumptions can’t be further than truth. What adds to the book’s credibility is that Sidhu was the head of the three-man RAW team in Gangtok, tasked to raise a united opposition to compel the Chogyal for the merger. The book defends the move, saying it not just “undid the wrong done by India to the people of Sikkim by denying them the right to accede to, and finally merge with, the Union of India”, but also protect its strategic interests in “this vulnerable and heavily defended sector” along the Sino-Indian border.

India no longer, writes Sidhu, had to depend on the whims and fancies, and the growing unpredictability of the Chogyal, who was getting restless—especially after his marriage with Hope Cooke, a young American he had met at a hotel in Darjeeling—to secure an independent status for Sikkim on the lines of neighbouring Bhutan. “Imagine the implications of a dissatisfied, sulking or even a revolting Chogyal in the background of a Doklam-like face-off between China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the Indian Army, with the Communist Party of China’s People’s Daily publication, Global Times, threatening to incite revolt in Sikkim against India,” the author reminds us.

By G.B.S. Sidhu; Publisher: Penguin; Price: Rs 599

Sidhu’s assessment of the Chogyal is in sharp contrast to that of a “benign, benevolent” king. “Thondup was like a man possessed. He was possessed with the idea of securing independent status for Sikkim, like the one enjoyed by neighbouring Bhutan, whose king was a relative of his.” But in doing so, adds the author, “he became totally oblivious to the changed geopolitical realities and India’s security interests in Sikkim.”

One finds a similar portrayal of the Sikkimese king in Andrew Duff’s account, which seems largely sympathetic to the royalty, but bereft of any romanticism attached. The British journalist, for instance, quotes Henry Kissinger asking one of his staffers, Mr Atherton, why India “annexed” Sikkim. To this Mr Atherton replied: “I don’t think they (India) really wanted to take this last step, until the Chogyal started to assert more authority than he had. And he made some statements at the coronation of the King of Nepal publicly, which upset the Indians.”

Duff mentions several instances of Thondup aggressively seeking an independent identity for Sikkim, despite the geopolitical scenario turning more complex and grim for the Himalayan state, especially since the debacle of 1962. Several local newspapers had also come up in recent years, calling for Sikkim’s independence. Coupled with these, the presence of the king’s American wife must have alarmed the Indian authorities. Hope Cooke, on her part, did very little to change the perception of her being a CIA agent (interestingly, Sidhu disapproves the idea of her being a CIA agent), indulged as she did in cultivating powerful friends in the West, and, worse, she wrote a piece in 1966 arguing that Darjeeling should be returned to Sikkim. These developments, especially in the post-Nehruvian set-up, made Sikkim appear as “the weakest buckle in the Himalayan belt”.

Also, to the Chogyal’s disadvantage, Indira Gandhi didn’t have her father’s nostalgia and romanticism associated with the Himalayan state, a notion which had in the past discouraged any democratic opposition to acquire critical mass in Sikkim. Things worsened further when P.N. Haksar and P.N. Dhar became Principal Secretaries and overturned the pro-Chogyal line of Foreign Secretary T.N. Kaul. Till then, writes Sidhu, the word merger was a “varjit swar” (prohibited word) in the corridors of power.

Sidhu, however, concedes that the timing of using a heavy-handed Indian Army operation to disarm the Sikkim Guards was a mistake. The author believes the Foreign Office misread the situation and, in panic, pulled in the Indian Army into action that was highly avoidable. “The disarming of the Sikkim Guards a day before the Assembly passed the resolutions, made the whole operation look as if it was undertaken to neutralise opposition from within the Sikkim Congress legislature group to the proposed passing of the merger-related resolutions in the Assembly on 10 April, which was far from the truth,” he writes.

The book is also significant for the fact that it attempts to correct the distorted image of Kazi Lhendup Dorji, the man who successfully led the democratic movement in Sikkim, but got marginalised politically and was later, unfortunately, accused of selling his “country” to India. Sidhu, while throwing fresh light on him, concedes that when Kazi was being attacked viciously, no Indian agency or person in authority chose to do anything to neutralise such false and motivated propaganda. Kazi was the real hero of the Sikkim saga, but the nation chose to ignore, worse, forget him.

Sidhu, with this book, puts the record straight as far as Sikkim’s merger with India is concerned. There were other books, especially M.K. Dhar’s Open Secrets: India’s Intelligence Unveiled, which in the past challenged the Gangtok-centric narratives, but they lacked the gravitas, originality and even authenticity which Sidhu brings in this volume. Sikkim: Dawn of Democracy offers an incisive insight into how India, 28 years after stupidly thwarting Sikkim’s merger with it, could prevent another Himalayan blunder from happening, just in the nick of time.