These stories about various animals by modern Indian writers challenge the centrality of the human figure in literature, writes Sumana Roy in her introduction to Animalia Indica.

As I write this, more a response than an introduction to a book of delightful stories by Indian writers about animals, I hear my seven-year-old nephew playing in the background. He wants to be an animal—most of his games involve impersonations of his favourite animals. I’m tempted to join him and his friend in the game, and I do, unable to hold myself back after I hear him say, “Then you’ll fall down and die—all dinosaurs died like that, falling down.” His friend attempts to mimic the imagined dinosaur, I come in and pretend to be another dinosaur, but am immediately shooed away: “You’re a human, you can’t play with us.”

I want to ask my nephew what makes him want to imagine himself as an animal. It is a question I’d have liked to ask Kafka and the storytellers of the Panchatantra and the Jataka Tales. On the other side of language is the question I’d have liked to ask those we call animals—do they ever play games or tell stories imagining themselves as humans? It is possible that only the human is aware of being human in a way that an insect or bat isn’t.

My nephew is not alone in his desire to become an animal, of course. Cinema, television shows, literature, video games, the automobile industry—all of these attest to man’s subconscious desire to experience animal life as if we were not animals at all. There’s a bit of forgetfulness involved here, and a little bit of desire—a playfulness and curiosity that works both ways now, in animals being turned into residents of human spaces, of homes and zoos, as well as the human’s imagined life as a hybrid, half-human and half-animal.

I write this sitting inside a plane—I’m acutely aware of the animal like ambition, to be a bird temporarily. So many humans inside a bird, in a way there can’t be in the zoological world. The aeroplane is modern man’s Trojan horse—man becoming animal, that animal swallowing many, many men temporarily, only to disgorge them later. As I began to collect stories for this anthology, helped by my editors, David Davidar (whose idea this book is, and who has directed me to most of the stories here), Aienla Ozukum and Isha Banerji, I had the sense of the blood of the Panchatantra running through the writers of the 20th century in a way I hadn’t anticipated at all.

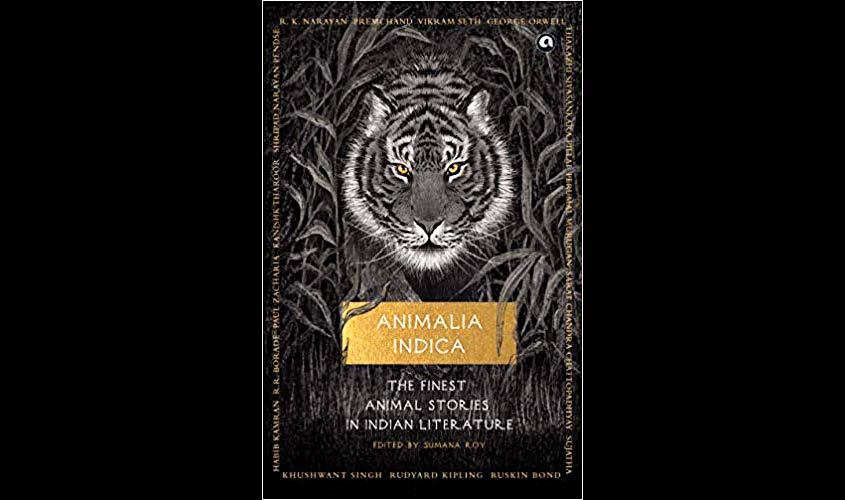

Animalia Indica: The Finest Animal Stories in Indian Literature is the first anthology of its kind in the Indian subcontinent. While its ancestor might be seen to be the Panchatantra, with life and living illustrated through stories of animals, we are never allowed to forget that these animals are stand-ins for human prototypes. Morality is the axis of these ancient animal stories, common to almost all cultures across the world. The stories in Animalia Indica, written in the last one hundred years or so, in English and translated from various Indian languages into English, make us aware of how far the modern Indian has come from the moral imagination of the anonymous storytellers and story collectors of the Panchatantra and the Jataka Tales. Industrialisation, journeys to the city, and the city itself led to the marginalisation of animals from urban lives not just physically but also in the imagination. These stories by modern Indian writers, about goats and cows, birds and dogs, horses and snakes, and various other animals, give us unexpected pleasure in the discovery of a self within us of whose existence we are mostly unaware or even forgetful. These stories also challenge the centrality of the human figure, an inheritance from the Renaissance that now controls our storytelling impulses. They allow us to live like the best stories do—live another life, becoming a lizard on a window sill, an ant between toes, lice in hair, or zebras in zoos. This book is, however, not a zoo, a show of exhibits—it is a sanctuary, of human-animals with the needle tipping slightly towards the right. A modern European imagined a human turning into an insect about a hundred years ago. It changed Western literature and popular culture.

Has something similar taken place here? The hundred odd years that we chose as chronological bookends for this anthology owe as much to our curiosity to study this, as also our interest in how Homo sapiens from the Indian subcontinent started looking at their relationship with animals after 1859, after Charles Darwin had made us aware that we, too, were only animals.

The awareness of these developments, of science annotating the imagination, made us decide that folk tales or children’s stories, whose character had remained largely unchanged, did not really belong to this book. The logic of selection that we’d set ourselves, primarily with the time period, meant that we would need to include not just “Indian” writers but also those like George Orwell and Rudyard Kipling, those who had lived in the country and written about animals—these stories (and I say “story” even though Orwell’s “story” is bibliographically listed as an essay, because the subject is based on what we now know to be a piece of fiction) allow us an entry into the colonial imagination and its relation with animals. Nearly half of these stories were written originally in English; apart from a few excerpts from long fiction, Motilal Kemmu’s Hindi novella, Perumal Murugan’s novel about a black goat, Nilanjana Roy’s novel about cats and their familiars in Delhi, and Ruskin Bond’s novella about a tiger, the rest are short stories. As we looked through translations of stories from the Indian languages, we noticed that many of these stories did not travel well when translated into English. Another word about the selection: this anthology does not aim to be representative—not of India and its languages (this book is not an encyclopaedia); nor is it a version of a natural history museum where all specimens of animal life can be found.

The title is quite self-explanatory: “Animalia” refers to the animal kingdom, and “Indica”, an older name of India found in Greek and Latin texts, to writers from India. The writers are “Indian”, but is there such a thing as an “Indian animal” too? A little earlier, I mentioned a European writer imagining a human turning into an insect—one of the transformative moments in modern literature. What is the Indian counterpart to that revolutionary act in European literature? Or, to put it differently, how have “Indian” animals marked our literature? Do the animals in the Panchatantra and Aesop’s Fables behave similarly or in different ways in similar situations? Is it possible that the birth of our nation, the invasion of technology, and the rise of individualism affected animals as much as they did humans? The Indian cow, to take the easiest example, is quite obviously not the same as the “non-Indian” cow, and the Indian elephant is not the same as an elephant from other parts of the world. As the scholar Rachel Dwyer reminds us: “Early Europeans found the animal gods of Hinduism the most distasteful…they were seen as ‘primitive’, or ‘low class or indigenous’. In other words, these deities were seen as too worldly compared to the more abstract, classical deities. Yet, other deities are also animals or part animal, including the avatars of Vishnu; Hanuman; and many mythical creatures, and the Jatakas tell the stories of the Buddha’s incarnations in various animal forms.” I am tempted to believe that these aren’t just stories by Indian writers about animals; these are stories by Indian writers about Indian animals.

Extracted with permission from ‘Animalia Indica: The Finest Animal Stories in Indian Literature’, edited by Sumana Roy, published by Aleph Book Company