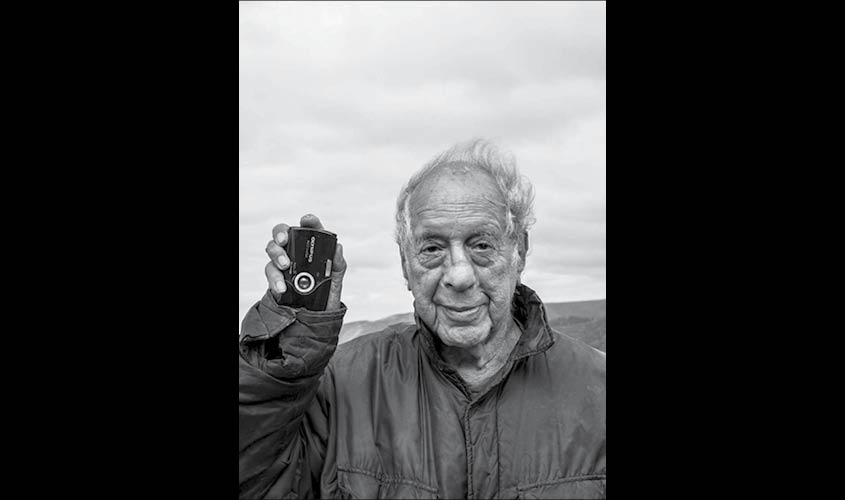

Robert Frank, one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century, whose visually raw and personally expressive style was pivotal in changing the course of documentary photography, died Monday in Inverness, Nova Scotia. He was 94.

His death, at Inverness Consolidated Memorial Hospital on Cape Breton Island, was confirmed by Peter MacGill, whose Pace-MacGill Gallery in Manhattan has represented Frank’s work since 1983. Frank, a Manhattan resident, had long had a summer home in Mabou, on Cape Breton Island.

Born in Switzerland, Frank emigrated to New York at the age of 23 as an artistic refugee from what he considered to be the small-minded values of his native country. He was best known for his groundbreaking book, “The Americans,” a masterwork of black and white photographs drawn from his cross-country road trips in the mid-1950s and published in 1959.

“The Americans” challenged the presiding midcentury formula for photojournalism, defined by sharp, well-lighted, classically composed pictures, whether of the battlefront, the homespun American heartland or movie stars at leisure. Frank’s photographs — of lone individuals, teenage couples, groups at funerals and odd spoors of cultural life — were cinematic, immediate, off-kilter and grainy, like early television transmissions of the period. They would secure his place in photography’s pantheon. Cultural critic Janet Malcolm called him the “Manet of the new photography.”

But recognition was by no means immediate. The pictures were initially considered warped, smudgy, bitter. Popular Photography magazine complained about their “meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposures, drunken horizons, and general sloppiness.” Frank, the magazine said, was “a joyless man who hates the country of his adoption.”

Frank had come to detest the American drive for conformity, and the book was thought to be an indictment of American society, stripping away the picture-perfect vision of the country and its veneer of breezy optimism put forward in magazines and movies and on television. Yet at the core of his social criticism was a romantic idea about finding and honoring what was true and good about the United States.

“Patriotism, optimism, and scrubbed suburban living were the rule of the day,” Charlie LeDuff wrote about Frank in Vanity Fair magazine in 2008. “Myth was important then. And along comes Robert Frank, the hairy homunculus, the European Jew with his 35-mm. Leica, taking snaps of old angry white men, young angry black men, severe disapproving southern ladies, Indians in saloons, he/shes in New York alleyways, alienation on the assembly line, segregation south of the Mason-Dixon Line, bitterness, dissipation, discontent.”

“Les Americains,” first published in France by Robert Delpire in 1958, used Frank’s photographs as illustrations for essays by French writers. In the American edition, published the next year by Grove Press, the pictures were allowed to tell their own story, without text, as Frank had conceived the book.

— ‘Snapshot Aesthetic’

Frank may well have been the unwitting father of what became known in the late 1960s as “the snapshot aesthetic,” a personal offhand style that sought to capture the look and feel of spontaneity in an authentic moment. The pictures had a profound influence on the way photographers began to approach not only their subjects but also the picture frame.

Frank’s aesthetic — as much about his personal experience of what he was photographing as about the subject matter — was given further definition and legitimacy in 1967 in the seminal exhibition “New Documents” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The show presented the work of Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand, who at the time were relatively little known younger-generation beneficiaries of Frank’s pioneering style. The show established all three as important American artists.

Robert Louis Frank was born in Zurich on Nov. 9, 1924, the younger son of well-to-do Jewish parents. His mother, Regina, was Swiss, but his father, Hermann, a German citizen who became stateless after World War I, had to apply for Swiss citizenship for himself and his two sons.

Safe in neutral Switzerland from the Nazi threat looming across Europe, Robert Frank studied and apprenticed with graphic designers and photographers in Zurich, Basel and Geneva. He became an admirer of Henri Cartier-Bresson, who co-founded the photo-collective Magnum in 1947 and whose photographs set the standard for generations of photojournalists.

Frank would later reject Cartier-Bresson’s work, saying it represented all that was glib and insubstantial about photojournalism. He believed that photojournalism oversimplified the world, mimicking, as he put it, “those goddamned stories with a beginning and an end.” He was more drawn to the paintings of Edward Hopper, before Hopper was widely recognized.

“So clear and so decisive,” Frank told Nicholas Dawidoff in 2015 for a profile in The New York Times Magazine. “The human form in it. You look twice — what’s this guy waiting for? What’s he looking at? The simplicity of two facing each other. A man in a chair.”

Early on, Frank caught the eye of Alexey Brodovitch, the legendary magazine art director, who gave him assignments at Harper’s Bazaar. Over the next 10 years, Frank worked for Fortune, Life, Look, McCall’s, Vogue and Ladies’ Home Journal.

Restless, he traveled to London, Wales and Peru from 1949 to 1952. From each trip he assembled spiral-bound books of his pictures and gave copies to, among others, Brodovitch and Edward Steichen, then the director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art.

Walker Evans’ book “American Photographs,” which was not well known in the 1950s, may have been the greatest influence on Frank’s landmark “Americans” project.

“When I first looked at Walker Evans’ photographs,” he wrote in the U.S. Camera Annual in 1958, “I thought of something Malraux wrote: ‘to transform destiny into awareness.’ One is embarrassed to want so much of oneself.”

While the photographs in “The Americans” are the most widely acknowledged achievement of Frank’s career, they can be seen as a prelude to his subsequent artistic work, in which he explored a variety of mediums, using multiple frames, making large Polaroid prints, video images, experimenting with words and images and shooting and directing films, like “Candy Mountain” (1988), an autobiographical road film directed with Rudy Wurlitzer.

Still, it is “The Americans” that will probably endure longer than anything else he did. In 2007 he consented to hang all 83 of the book’s photographs at the Pingyao International Photography Festival in China, in celebration of the book’s 50th anniversary. And in 2009, the National Gallery of Art in Washington mounted “Looking In: Robert Frank’s ‘The Americans,’” an exhaustive and comprehensive retrospective of his masterwork, organized by Sarah Greenough. The show traveled to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Frank acknowledged that in photographing Americans he found the least privileged among them the most compelling.

“My mother asked me, ‘Why do you always take pictures of poor people?’” Frank told Dawidoff in The Times Magazine. “It wasn’t true, but my sympathies were with people who struggled. There was also my mistrust of people who made the rules.”