Last few weeks have seen a lot of newspaper headlines and lively (or perhaps livid) TV debates on the economic slowdown in India. There has been a spirited attempt on the part of the government and its institutions to term this phase as a period of “cyclical slowdown”. They seem to genuinely believe that this would soon be over, with the government announcing a host of measures to address the issue. On the other hand, the independent analysts are of the view that even if slowdown is cyclical, India needs to carry out some structural reforms for growth.

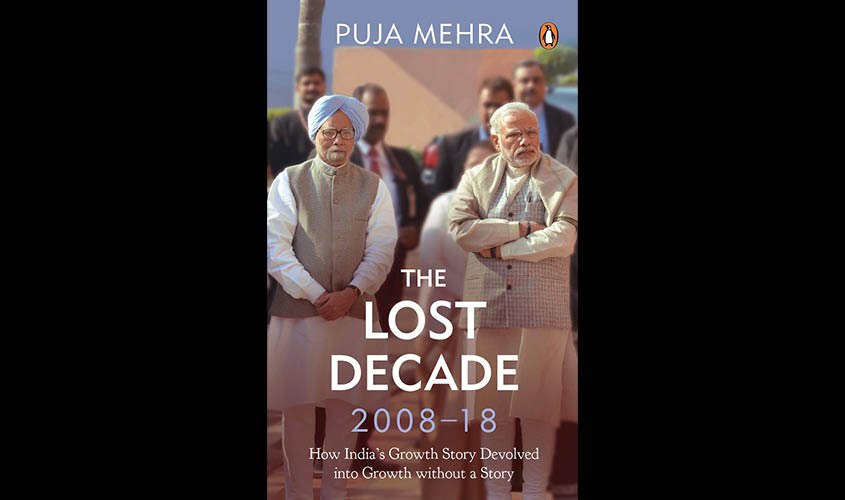

Now that is a debate full of economic jargon which would not make much sense to a layperson. S/he would be more keen on their job security. For youngsters, their main concern would be getting a decent job. Although this book “The Lost Decade: 2008-18” by Puja Mehra came early this year, this writer picked it up for reading (and review) only recently with the hope of understanding the current economic “slowdown” with a sense of perspective and context. And it actually helped. The book which has an apt secondary title “How India’s Growth Story Devolved into Growth without a Story” has been published by Penguin Random House and now also available in Kindle edition.

The book certainly makes the complex economic issues easy to understand and conjoins the political issues with them effortlessly. Yet, it is no primer on economic issues either—on the contrary, it tells you the impact of politics on the economic policies in a simplified manner or perhaps some may argue in over-simplified manner.

Based on numerous interviews that the author conducts with the top decision-makers during this period, and after studying the impact of various economic decisions, she infers that the growth potential of the economy is not being realised because of the constraints placed on it by an irresponsible political system irrespective of the political dispensation occupying the office.

The book has been organised in four segments. These throw light on various important decisions which had an impact on the economic and financial health of the country. The first segment deals with the seriousness of the global financial shock during 2008-09, commonly known as subprime crisis, when the panic paralysed the financial system across the world. The author painstakingly recounts the events of that time and convincingly makes a case that the Manmohan Singh-led UPA-I deftly handled the crisis and ensured that country’s financial institutions including PSBs survived the severity of the shock.

Whereas the first segment applauds the Manmohan-led government, the second one castigates it for frittering away all that was achieved in the previous some years. The segment titled “A Recovery Destroyed (2009 -12)” discusses in detail as to how events, mostly political in nature, destroyed the recovery. The most interesting part of this segment details the events that led to installation of Mr Pranab Mukherjee as Finance Minister as former Finance Minister Chidambaram had to be shifted to the Home Ministry following Shivraj Patil’s resignation in the aftermath of the Mumbai terror attacks. After which, Prime Minister Singh kept Finance with himself but as the fate would have it, he had to undergo a coronary bypass surgery and was out of work for several weeks.

Mukherjee had held the finance portfolio 24 years ago, in Indira Gandhi’s cabinet—but the finance and economics had changed fundamentally and structurally since then. Puja Mehra contends that Mukherjee still seemed to swear by the socialist-era ideology which was out of tune with global economic affairs. So the second segment focuses on what she calls “missteps” and “ill-advised policies and self-serving politics” which disrupted the nascent recovery made after subprime crisis.

The first such misstep was a third package of fiscal stimulus at a time when Manmohan Singh was still out of work post-surgery, and for which Mukherjee did not obtain cabinet approval. This decision, Puja opines, ended up hurting rather than accelerating economic recovery. The next couple of years saw many such decisions —higher allocations for social sector ignoring the expanding fiscal deficit and economy’s capacity for absorbing the fund releases productively.

The third segment (A Slow Recovery Again–2012-15) focuses on Chidambaram’s comeback tenure as Finance Minister with 18 months to go before the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, which featured bringing in Raghuram Rajan as the RBI chief. “The two fire-fighters ensured the inflation rate, fiscal deficit and current account deficit were contained,” the author notes. She constructs the argument that the economy Narendra Modi inherited in 2014 was recovering from severe macroeconomic shocks. The Modi wave had unleashed tremendous hope and energy but it didn’t translate into a coherent plan of action for economic revival, she concludes.

In an otherwise well-structured work, this segment, despite being loaded with lots of information, is somewhat wobbly and seems to digress at times. Apart from other issues, this dwells on the role of the Central Bank and the NITI Aayog and the importance of their independence from the finance ministry. The author makes some interesting observations here, such as, “The other reason NITI Aayog couldn’t quite take off was Modi’s disinterest in institutions and his disinclination for intellectual inputs”.

The last segment (Another Recovery Destroyed–2016-18) argues that the major economic policies of the Modi government were based on political calculations rather than economic prudence. The modest but steady economic recovery that Modi had inherited from the previous government was disrupted. This part chronicles various decisions (and indecisions) of Modi government —demonetisation, imperfect GST and complete disregard for NPAs receive generous attention from the author. She has criticised the media for eulogising the demonetisation move, purely on social media rumours.

If the journalist in Puja Mehra has helped her simplify complex economic issues easier, the economist in her has critically scrutinised the policy decisions made in the decade 2008-18. She gives her verdicts unflinchingly and unambiguously at various points. Irrespective of the government in office, she has been unsparing in her criticism of the decisions which she believes have hurt the economy.

She concludes her marathon analysis with this—“The last 10 years have shown that half-baked, ill-thought-out measures produce uncertain results. Be it the land acquisition law, the national food security law, demonetisation or GST. The big-bang economic reforms agenda has plateaued. We need to rebuild consensus for a steady stream of reforms and revive the spirit of 1991”.

Vidya Bhushan Arora is an independent journalist and runs a web-magazine raagdelhi.com.