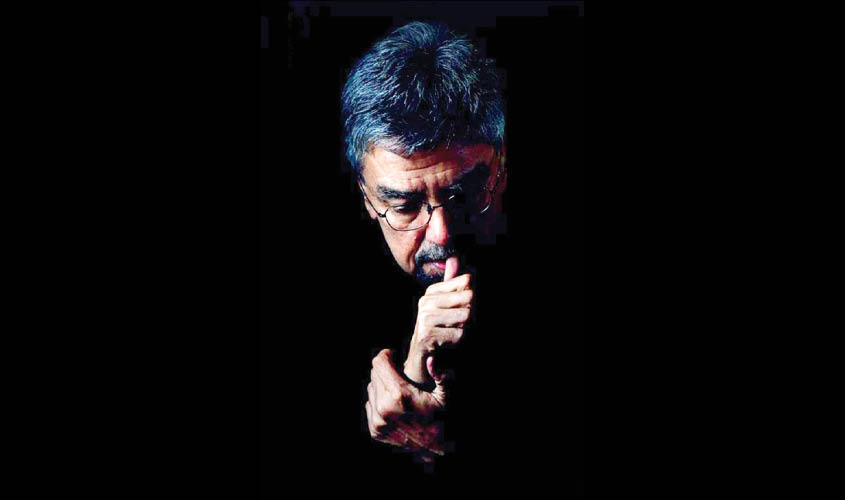

In his debut novel, which blends historical truth with fiction, director and scriptwriter Khalid Mohamed tells the story of six maverick sisters living through India’s Partition. An excerpt.

Qalayat, pronounced “Qaleth”, hasn’t been mapped yet. A cross between a village and township in the Jind district of Haryana, it’s an enclosure empty of monuments and landmarks.

The state of Haryana, in northern India, was formed following the Punjab Reorganisation Act in 1966, much after the opening chapter of the story of the six Aladia sisters.

The name “Punjab”, signifying a confluence of five rivers, had been coined centuries ago by the Central Asian Turkish conquerors, and popularised by the Mughals. But that’s for the history books.

In 1966, the state was sub-divided on the criterion of the languages spoken by the inhabitants in its diverse seams and folds.

The sub-districts of Jind and Narwana in the Sangrur province, home to Qalayat, were subsumed into the neo-demarcated state of Haryana, denoting Abode of the Gods. Implacably to date, the administration has been quick to playing the game of divide and govern.

The ongoing division of states in post-Independence India has been largely benign. No tragic upheavals. At most, the lines drawn were akin to fleeting worry wrinkles.

The Punjab-Haryana divide wasn’t comparable at all to the British barrister Sir Cyril Radcliffe’s line of partition in 1947, splicing a sub-continent into India and Pakistan.

Poet W.H. Auden had written about Sir Cyril, describing him wryly as “unbiased”. Or “at least he was when he arrived on his mission/ Having never set eyes on this land he was called to partition/ Between two peoples fanatically at odds/…(given) four judges, two Moslems and two Hindus, to consult with.”

The epochal split was red-inked by the clueless British barrister. He had never been east of Paris. India couldn’t have been more than an enormous canvas of a colony which had to be tinted in bewildering, separatist shades of brown.

During the near two centuries-long British Raj, territorial lines were unthinkable. Whether under subjugation or after Independence, the Aladia sisters had come to regard themselves as a fusion of Punjab and Haryana. The sisters’ spoken dialect was polyglot, their vocabulary a zingy mix of Urdu and Punjabi. Their accents were thickly Haryanvi, the n’s spiky, the vowels abbreviated, and the syllables stretched.

The state rupture confused the next generation of the Aladias. They couldn’t pinpoint whether they were Haryanvi Jats or Punjabis. Regional identification was kept at bay, with the rejoinder, “We are Haryanvi-Punjabis, both!” or more generically, “We’re from somewhere in north India.”

Today Qalayat, a fractious acreage, kindles images of water-pumps irrigating wheat, millet and paddy fields. Filigreed tumbledown fast-holds have been fabricated into squat cement-block homes. Doppelganger brick kilns abound. A moss-cloaked mosque topped by a marble dome racked with indigo stone veins, co-exists with the burgeoning Hanuman temples sculpted into the tired trunks of peepul trees—kin to the Bodhi under which between the fourth and sixth centuries B.C., Gautam Buddha is lored to have attained Enlightenment.

By Khalid Mohamed; Publisher: Om Books International; Pages: 260; Price: Rs 225

Crows peckish as they are anywhere, lounge in the grass pockets toasted by the sun to a tobacco brown. Eagles, kites and vultures soar, on the lookout for a landing point for carrion. Matronly sows grunt, fearing clawed attacks. The cattle, some skeletal, others well proportioned, graze peaceably at dry bushes and tufts. They are protected as much by celestial beings as by crucified scarecrows, and children wielding stone catapults in case the eagles transgress the rules. Dogs of no recognisable breed bark raucously whenever the predatory birds flap too close for comfort.

The term “village”—or its first cousin “township”—is anachronistic. Yet, it’s handy for annotating the yawning tracts of land dotted with ridges, rivulets and dugouts. On this 21st-century rural scape, collective rejoicing still erupts with the introduction of electricity. The benediction of machine-generated power is celebrated, even though the lights in the areas of darkness come on and go off coquettishly. Rustics can’t be choosers. Relief and gratitude are writ large on the rarely expressive faces, transiently. Deep, focused attention is accorded to the let-there-be-light—battiyan jalao—ceremony a month before the quinquennial general elections.

Votes count, manipulated by money-in-cash allurements and orations about an improved life. Primeval amenities attached to row houses, stucco two-storeyed blocks and retail shops are contracted to the most up-to-snuff spokesmen of the constituency, who change as swiftly as their political affiliations, motivated by considerations of caste and creed, of the inclusive and the exclusive. Rancour behind the rejoicing simmers.

Qalayat is prototypical. Electoral promises and payoffs transmute into terminal deprivation. Enough is never enough. Between 1857 and 1948, administrators of the British Raj didn’t deign to go there. They made no promises. That would have meant thankless effort. Presumption: the natives wouldn’t have submitted to the kindness of the sola-hatted strangers.

Endemically, the priorities of the British authorities precluded chunky slices of India: the villages were conjectured to be as barren as the kilns. No Governor General had heard of Qalayat.

The Marquesse of Willingdon, Freeman Freeman-Thomas, during his governor generalship, had heard of the Aladia sisters in passing, of the six child-women who were in the process of formulating a pact to take a city, any city, by its balls, the balls of a city kept under perpetual surveillance by the British, if need be. Through an illegibly scrawled postcard, the sisters had sought audience with the lord. Bemused, Freeman-Thomas had blinked, “What?” Audience wasn’t granted. The girls—or were they women?—were dismissed as nubile harlots, conniving a clearance to hobnob with the goras.