Kashmiri scholars and writers from the Hindu community have demanded the official recognition of Devanagari script for writing the Kashmiri language, arguing that this would make the language more accessible to Kashmiri Pandit youths. This is being opposed by Kashmiris settled in the valley, as they have been using the Nastaliq script—a calligraphic script used to write Arabic, Persian and Urdu languages—to write Kashmiri for centuries. Currently, Nastaliq is the only official script for Kashmiri language.

The KP community, which was driven out of the valley since the onset of militancy in 1990, has been trying to keep its culture and identity intact. The language struggle has cropped up as a major issue facing them, with KP scholars alleging that the community is at the receiving end of a cultural assault by elements in the valley who want to replace the original Kashmiri identity with one imported from outside.

A group of Pandits met the former HRD minister Smriti Irani last year with the proposal to allow the use of Devanagari to write Kashmiri officially. Talking to The Sunday Guardian, Sunita Raina Pandita, a prominent Kashmiri Pandit author, said, “While the minister seemed sympathetic, many organisations in Kashmir immediately organised emergency meetings to oppose this proposal with full force.” Pandita said that the Jammu and Kashmir Vichar Manch will now meet the new HRD Minister, Prakash Javadekar to apprise him of their demand.

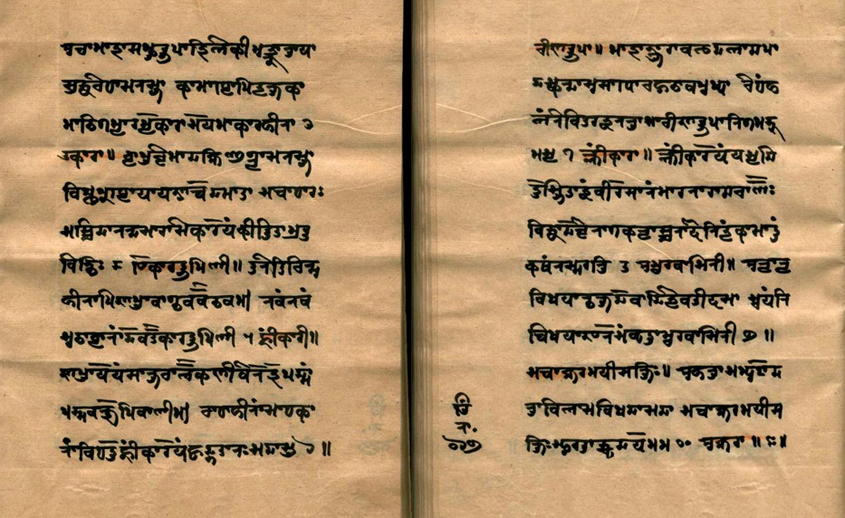

Dr Shashi Shekhar Toshkhani, a leading linguist who has tried to prove with his pioneering work that Kashmiri language has descended from Sanskrit like most other Indian languages, and not from the Central Asian Dardic family, as was thought earlier, added: “They (Kashmiris in the valley) say that allowing Kashmiri to be written in Devanagari would be an assault on their culture. Even when I suggested writing it in Roman script, one prominent writer said that there would be ‘rivers of blood’ in Kashmir if that happens.” Toshkhani is of the view that Devanagari is similar to Sharada, which was the original script for the Kashmiri language. He said that Nastaliq was not compatible with Kashmiri and had to be modified for it to be suitable to the language.

But scholars in the valley feel that doing away with Nastaliq will not be reasonable. Abid Ahmed, editor at the J&K Cultural Academy of Art, Culture and Languages, feels that Nastaliq is important for historical reasons: “Nastaliq has been in use for centuries. Having Devanagari as script would lead to difficulty in studying the literature produced over a large period of time.”

The demand to use Devanagari is being opposed by Kashmiris settled in the valley, as they have been using the Nastaliq script, used for Arabic and Urdu , to write the Kashmiri language.

But the quarrel over the script forms only one part of the divisions between Kashmiri Pandits and Kashmiri Muslims over the language. Already there are significant differences between the Kashmiri spoken by the two communities. According to Toshkhani, people in the valley are increasingly using Persian and Arabic words in place of the ones already present in Kashmiri language, “For example, sun is called siri in Kashmiri, but they call it aftab. Water is paun in Kashmiri, but it is now called aab.” This Dr Toshkhani feels is part of a larger agenda of changing the character of the language: “More and more Perso-Arabic words are being thrust into Kashmiri to suppress its true identity. This is being done for purely political reasons.”

He says that Kashmiri is anyway getting pushed to the background by Urdu and the universal craze for English. “Those who claim to be fighting for Kashmiriyat, themselves prefer to speak in Urdu or Persian and even Arabic, rather than Kashmiri,” Toshkhani alleged. He blamed Sheikh Abdulla for the spurt in Urdu. He said that it was Sheikh Abdullah who claimed that Urdu was disappearing from the rest of India and needed to be kept alive in Kashmir. Until some time ago, Kashmiri was not even taught in the schools of the state.

However, the view from the valley is quite different on this issue. Many scholars and writers contacted by The Sunday Guardian were of the opinion that Urdu’s position as the official language is helpful considering the diversity of the state. Professor Gul Wani of Kashmir University said, “Urdu is used by middle and upper class families because they find it ‘fashionable’ and not due to any ideological reasons.” Muslim scholars in the valley do not see any politics in the use of the Nastaliq script either. In fact, scholars such as Marghoov Banehali, Amin Kamil and Rehman Rahi challenge the theory that Kashmiri has Sanskrit as its origin. “According to most historians, the Kashmiri language belongs to the Dardic family (mostly used in northern Pakistan and Kashmir),” argued Gul Wani.

However, the view from the valley is quite different on this issue. Many scholars and writers contacted by The Sunday Guardian were of the opinion that Urdu’s position as the official language is helpful considering the diversity of the state. Professor Gul Wani of Kashmir University said, “Urdu is used by middle and upper class families because they find it ‘fashionable’ and not due to any ideological reasons.” Muslim scholars in the valley do not see any politics in the use of the Nastaliq script either. In fact, scholars such as Marghoov Banehali, Amin Kamil and Rehman Rahi challenge the theory that Kashmiri has Sanskrit as its origin. “According to most historians, the Kashmiri language belongs to the Dardic family (mostly used in northern Pakistan and Kashmir),” argued Gul Wani.

But this doesn’t convince the Pandit writers who see radical Islamist tendencies as the main cause for the marginalisation of the original Kashmiri. “There is no culture without language and by altering the nature of Kashmiri language they are trying to destroy the true cultural identity of Kashmir which is represented by the Pandits,” said Pandita. Both she and Toshkhani are pessimistic about the future of the language. Pandita said, “Since we are not a vote bank, we would have to come out on the streets to protest, otherwise politicians won’t heed our demand.”