FEROZE the forgotten GANDHI

Author: Bertil Falk

Publisher: Lotus Roli

Pages: 304

Price: Rs 695

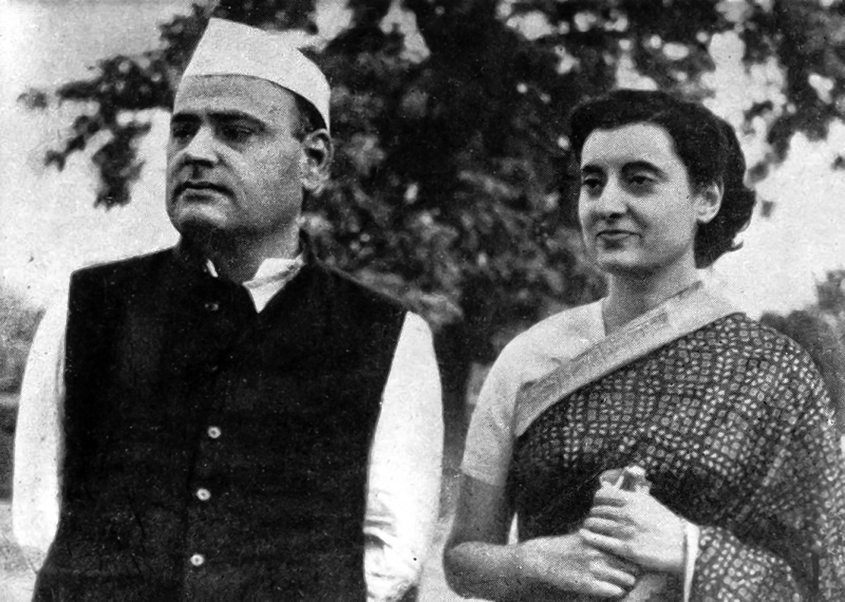

With a title as catchy as Feroze: The Forgotten Gandhi, the author Bertil Falk has taken the first seducing step towards covering the travails of Feroze Gandhi, whose name generally rings a faint bell in our hazy collective consciousness as Indira Gandhi’s husband. However, after Bertil Falk’s painstakingly-researched book on this forgotten Gandhi, one acquires a ringside view of the man, understanding him as a person of intellectual prowess, of impeccable integrity, of passionate patriotism, and a compelling orator to boot, but surprises of surprises, someone with technical aptitude, far ahead of his times.

The book, which is replete with many captivating pictures of him with Indira, his parents, Jehangir and Rattimai née Commissariat, Kamala Nehru at King Edward VII Sanatorium at Bhowali, his boys Rajiv and Sanjay, to mention simply a few. One of the very amazing ones is “a series of selfies, long before the word was invented” snapped in London by, obviously Feroze Gandhi — hence the selfie tag — showcase India’s first Prime Minister’s son-in-law as his very own person. To touch on a few anecdotes: While embarking for London, Feroze carried with him a letter from the Mahatma for Agatha Harrison who also happened to be a friend of Nehru’s. Presumably, the letter must have been written to ask the lady to provide assistance to the young Feroze in those foreign climes. Interestingly, Nehru too, had penned a letter to Ms Harrison introducing “Feroze Gandhy” — Gandhy, as he spelt it, not Gandhi. This Gandhi, one is informed, had been proposing to Indira ever since she was 16, but it was on the steps of the Basilica of Sacré Coeur, Paris that she betrothed herself to him. Her father’s primary objection to the marriage was that Indira was far too young to plunge into matrimony, thereby closing doors before they had opened. He wanted her to think the matter over, but Indira was adamant, categorically informing her father that unless he relented she would shut him out of her life and the daughter kept her word. While travelling with Paapu from Bombay till the train pulled into Allahabad, she pelted him with her stone silence — the sounds of silence lasting an unbroken fortnight. On arriving home, the worn-out father directed his secretary to book Indira’s ticket to England where she had earlier disclosed that she wanted to spend her remaining holidays with Feroze

in London.

Feroze had a passion for photography and daringly, while wandering in the jungle for photographing would cajole tigers to pose or rather pause for him, which, as reported, a lone tiger would halt for a second allowing the camera to capture the regal animal. His son, Rajiv, undoubtedly inherited this gift and facility from his father — the proof of which is to be found in Sonia Gandhi’s pictorial book Rajiv. Myriad moving snapshots taken by Rajiv portray him as a photographer framing nuanced moods and situations with impassioned élan. The writer also refers to a picture of Rajiv as a boy cradling a camera; in other words, in all likelihood, this would have been presented to him by his father. Another snippet: Feroze’s love for cars is a well-documented fact, and he took immense pride in keeping his black Morris spotlessly clean, polishing the car with great gusto. His opening the car’s bonnet, popping his head into it to tighten a screw here, or a bolt there, went beyond what would be bracketed under “Hobby”. The late Vinod Mehta describes him as, “a Tinkerer by Temperament”. It, therefore, is apparent that his younger son, Sanjay derived his delight and proclivity towards vehicles from his father and thus undoubtedly, the birth of the Maruti.

Feroze’s love for cars is a well-documented fact, and he took immense pride in keeping his black Morris spotlessly clean, polishing the car with great gusto. His opening the car’s bonnet, popping his head into it to tighten a screw here, or a bolt there, went beyond what would be bracketed under “Hobby”.

Yet another heart-warming fragment of a story: the boys were back from boarding school holidaying at Teen Murti — the Prime Minister and their Nana’s abode — when Feroze asked them to be brought to Parliament House. The brothers sat in the Visitors’ Gallery listening to a rousing speech delivered by their father. Afterwards he rushed towards them hugging the two in the same sweep. The scene, no doubt, is bound to make the readers’ eyes misty. Whatever little time he had with his sons, Feroze wanted to impart them with what he believed necessary lessons — like sawing wood. When chided by a friend for such menial training, he explained, “My sons have a very rich mother but a very poor father. I am making sure that they do not starve’’.

After the elaborate wedding of Indira and Feroze, where the dapper bridegroom’s mother insisted that her son wear the Parsi holy thread under his khadi sherwani, the lovely pair went to Kashmir to spend their honeymoon. Both strolling (one would visualise hand-in-hand) through the Mughal Gardens, wandering along the banks of the Jhelum, taking shikara rides on the Dal Lake, trekking up the pine-breezed mountains, buying trinkets on Srinagar’s floating cottage emporium… Bertil Falk here draws a contrasting parallel taking the reader back 26 years to Nehru’s own honeymoon with his bride Kamala. Here the groom had left his bride cooped up alone, while he accompanied with a cousin, went to shoot the breeze, up in the airy mountains.

Feroze was hardly 48 years old when he breathed his last. There had been a slackening in the relationship between husband and wife, and Nehru, towards the end, silently acknowledged his role in fraying the bond, and thus the couple along with their sons were sent to Kashmir — a second honeymoon of sorts — where it is believed frazzled nerves were soothed and many serene moments were spent under the canopy of Chinar trees.

When Feroze succumbed to his final heart attack and lay in state at the Prime Minister’s residence, verses were recited from the holy books of all foremost religions —the Gita, the Ramayana, the Koran, the Bible and the author is quite sure that hymns were delivered from the Guru Granth Sahib as well. A relevant matter must be brought up here was that a special prayer was also held for his departed soul by a Parsi priest. Another fact revealed, was that the Parsi Last Rites were conducted first. All non-Parsis, save his widow and two sons were cleared out of the room for this ritual. Feroze had favoured cremation over being laid to rest at the Tower of Silence.

Indira, always good at keeping her feelings to herself, gave everything away when she stated, “I do not like Feroze, but I love him”. The political aspects of Feroze Gandhi, for another day. For now, the forgotten Gandhi is no longer forgotten but resuscitated.