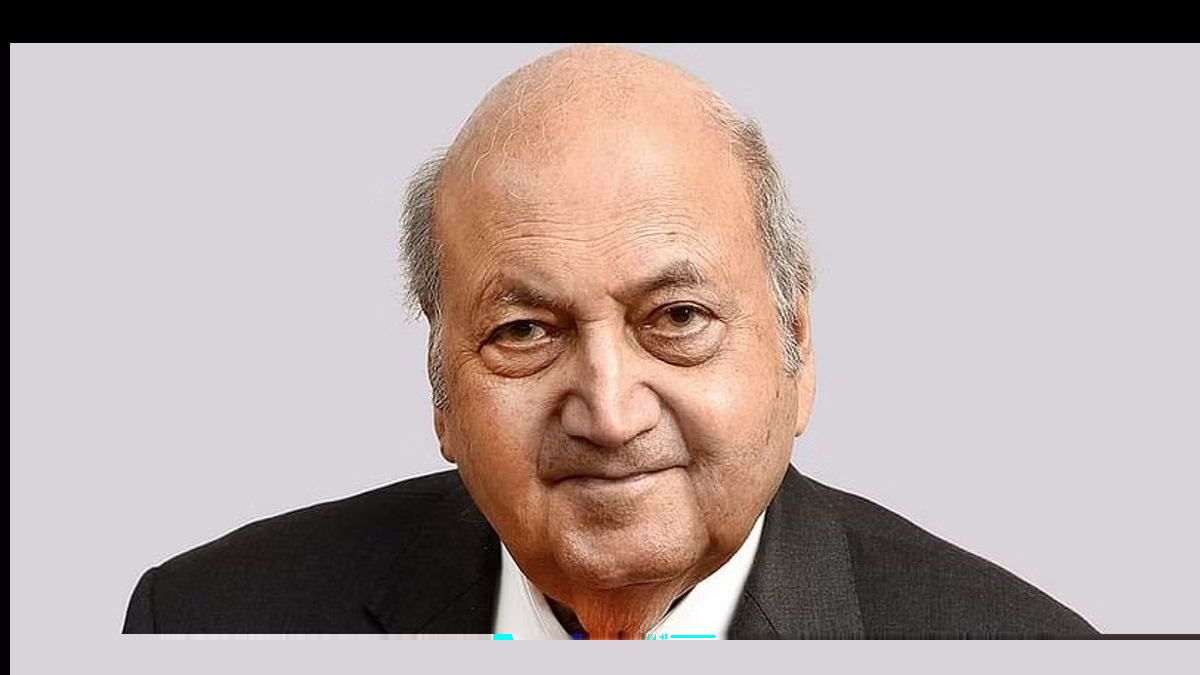

Keshub Mahindra was among India’s early promoter industrialists who trusted professional managers to run the company.

New Delhi: Padma awards list of 2002 announced on Republic Day included Keshub Mahindra, the doyen of Indian industry, who passed away on 12 April. The Congress-NCP government in Maharashtra, headed by Vilasrao Deshmukh, had sponsored his name for Padma Bhushan and the NDA government of Atal Behari Vajpayee accepted the suggestion. The industrialist politely refused the award on grounds of probity. Mahindra, who was Chairman of his family group, Mahindra & Mahindra, between 1963-2012, had been non-executive chairman of Union Carbide India Ltd (UCIL), the company whose Bhopal plant had leaked fatal gas in December 1984 causing thousands of deaths and maimed many.

A CBI charge-sheet was filed and Mahindra was named among eight top functionaries of UCIL. (It led to his conviction for two years in 2010—appeal against the magistrate’s order is pending in Bhopal Sessions Court since. Bail was granted to him by superior court within hours of his conviction.) In a letter to the then Deputy Prime Minister, Lal Krishna Advani, who as Home Minister oversaw the process of Padma awards, Mahindra thanked the government and said that as he was an accused in a case filed by CBI, it was perhaps not proper for him to be in the awards list and requested that the award be withdrawn. This so far is the only occasion when a Padma awardee pointed out a fallacy on grounds of probity and refused to be in the honours list.

Keshub Mahindra, like JRD Tata, trusted professional managers to run his group companies. Beginning with steel trading he diversified into manufacturing automobiles and tractors. (Mahindra today is the world’s largest tractor manufacturer by volume.) The Mahindra tractor factory was visited by Jawaharlal Nehru in 1961 as the company, along with public sector HMT, had ventured into an area essential for agricultural growth. Today M&M has tourism resorts (Mahindra Holidays), a Lifespaces company which provides quality housing, and is diversified from high-tech (TechMahindra) to defence (the M777 Howitzer deployed in Ladakh is assembled with Ango-US collaboration by the company). Along with his nephew Anand Mahindra, who succeeded him as chairman in 2012, Keshub Mahindra forayed into diverse sectors with success.

When Keshub Mahindra announced his retirement (he was chairman emeritus thereafter) in 2012 poignant scenes were witnessed in the company’s Kandivili plant in North Mumbai. Pawan Goenka, who now heads the government’s space initiative, Indian National Space Promotion Authorisation Centre (INSPACe), was then M&M’s Managing Director—an IIT alumnus who had a roaring career in US automobile in industry in Detroit, he had been entrusted by M&M to run the automotive and tractor verticals. Goenka went up to the podium and touched Keshub Mahindra’s feet in a befitting traditional Indian tribute. Seeing him, the leader of the workers’ union followed suit and one by one all workers of Kandivili similarly paid obeisance.

Port Sunlight near Liverpool in England, the birthplace of the international conglomerate, Unilever, has a memorial to the founder of the company, who passed away in 1925.The plaque reads,” Erected in the memory of William Hasketh Lever by his fellow workers of Port Sunlight”.

As tributes poured in from politicians, captains of industry, et al, the eulogy of two eminent professional managers, Pawan Goenka and the Maruti Suzuki Chairman R.C. Bhargava, stood out—they both underscored that while giving full autonomy to his managers Keshub Mahindra always introduced his employees as colleagues, not subordinates. He will be missed by his fellow workers in M&M and a host of companies he chaired. In October this year, he would have been a centurion. Former Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao was once asked by a group of editors who he hosted at tea, as to how he felt. Rao replied: “I feel like a 99-out batsman”, thereby emphasising that a player who finishes one short of 100 puts in hard work, but misses the grandeur. Keshub Mahindra never sought exaltation—even in death, he preferred to be “99 out”.