Traveling is often considered a rewarding experience for the soul, and if you happen to be an artist the reward increases manifold, as you can bring to bear the experiences you gather from different cultures on your work. The sights and sounds, the tastes and smells and even local interactions add fuel to your creativity and imagination. But what sort of motivation does an artist need to shift base from their country of origin and make another place their home?

The figure of the expat artist who makes India his or her adopted home has been integral to this country’s artistic tradition. For example, Samuel Bourne, a British photographer known for his landscape and architectural photos, lived here from 1863 to 1870. The Scottish doctor John Murray, another prolific photographer, relocated to India in the 1850s. The English painter George Chinnery, who created some of the more striking representations of the Indian sub-continent, spent around 24 years of his life in this part of the world.

To be sure, many of these artists were here owing to their links to the East India Company. Yet their artistic enterprises had little to do with their colonial ambitions. It was just that they’d found their muse in India.

American artist Waswo X. Waswo has been living in India — in Udaipur, Rajasthan — for the past nine years now. In his studio here, he makes hand-coloured portraits and sepia-toned photographs depicting Indian themes and imagery.

“It wasn’t until 2001 that I really began spending most of my time in India,” says Waswo, who had travelled to various parts of India, with this camera, before settling down in Udaipur. “In some ways I felt like a refugee from the America of George W. Bush. I had lived through Ronald Reagan, and didn’t want to experience that again under Bush. But it was really the beauty of India and its people that kept me here. Visa issues necessitated that I do a lot of ins-and-outs and back-and-forths, but India began to feel more and more like home with each visit. Today I always long for the country, especially Udaipur that has become the home of my heart. I do my best to spend the majority of the year there, though with a busy schedule and the problems of being a wishful immigrant, that is not always possible. I’ve learned what it is like to try to keep a home in a land that you really don’t belong to.”

Waswo had heard many stories from George, his father. George was stationed in India during World War II and had an album containing photographs from India, which further accentuated Waswo’s interest in the subcontinent.

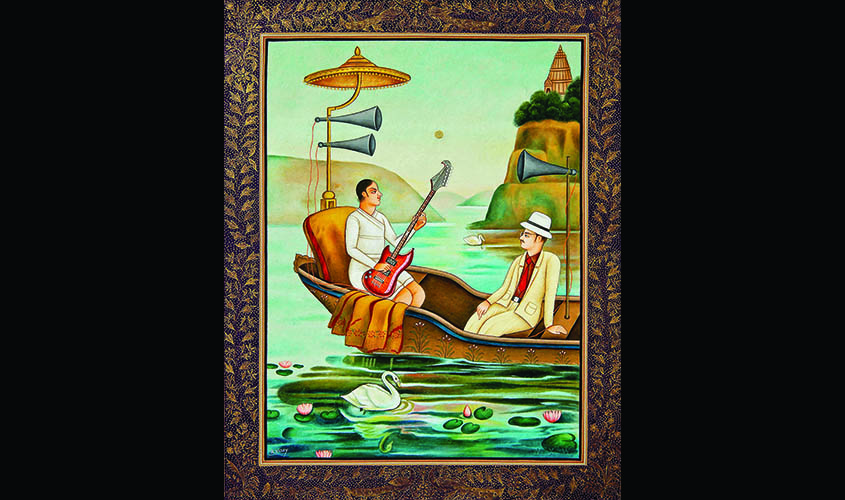

In his studio in Udiapur, Waswo collaborates with photo hand-colourist Rajesh Soni and miniaturist R. Vijay. “I make digitally shot portraits in the village of Varda, about a thirty-minute drive outside Udaipur, complete with painted backdrops and props that might be associated with the 19th-century ways of seeing, but I add a twist of the contemporary. These images are then printed in black-and-white, and Rajesh Soni, a third generation Rajasthani hand-colourist, applies all of the soft hues by brush. Together, we narrate a tale of the foreigner in India, sometimes directly autobiographical, and sometimes more generic and symbolic,” says Waswo.

Waswo has also built a collection of printed artworks that originated in India. His collection consists of woodcuts, etchings, lithographs, dry points, and serigraphs. He says, “It took me a decade to make this collection. It was a medium that wasn’t receiving much attention, so I sort of made it my crusade for a while by promoting other genres and other people’s work, which helped me fit into the Indian scene.”

Today, Waswo is pleased with his Indian art experience but hopes for better funding for local museums. He says, “The history of Indian art is rich and deep and can hold its own against any other country. The biggest problem is having this fact receive the recognition that it deserves, and a lack of proper museum structure within the country is the chief problem. What is most needed is a meaningful investment in art infrastructure.”

His relationship with India is primarily that of a guest who is deeply engaged with Indian art and adding his own perspective to the same. He says, “India caused me to re-examine the ways I approached subject matter as a Westerner. The ‘foreign gaze’ and Orientalism became key concerns and components in my practice. I’ve straddled a line between accepting criticism along these lines and responding to such criticism in a sometimes provocative manner. So my relation to the Indian art world is sometimes that of a welcome guest and sometimes that of an interloper. In ways I’ve come to relish my outsider status, as it gives me some perspectives and liberties that perhaps insiders do not have.”

But visual and performance artist Yuriko Lochan, who is originally from Japan, doesn’t like to use such words as “guest”, “outsider” or “foreigner” for herself. For her, India is home.

Yuriko is married to artist and former director

It’s been 30 years for Yuriko in India, and the obvious influence of Indian aesthetics reflects in her work. “I have learnt Carnatic music and looked at various motifs which I incorporated into my art,” says Yuriko.

She created her acclaimed painting Yamuna 25 years ago. It is inspired by Etawah city in Uttar Pradesh. She says, “I visited Etawah, the place where my in-laws are from. The painting is based on the view which I had experienced there — ghat, family temple roofs seen from the top of the hill temple, blessing the small city. Once the river and the people’s life were tightly connected, but no more. The work was exhibited in Mumbai and Delhi in 2000 and 2003 respectively.”

Another of her works, Jeevan, was exhibited in Mumbai in 2000 and it depicts the life of the people who depend on the sea for their livelihood. She says, “In Puri, Odisha, I saw small fishing boats far in the middle of a swirling sea. I was taken aback by the boldness of the people who can rely on a simple boat for the catch. It was actually four logs tied to each other. The sea is the life of the people there, and the title Jeevan came from this impression on my mind.”

Adjusting in a new country, despite all the teething troubles, was never a problem for Yuriko. She says, “I was barely 25 years old when I moved here. I had no idea of the culture and people in India. As I was young, I was thinking very ideal/utopian things about my surroundings but I was wrong. Every country has its share of problems but I didn’t let that hamper my practice. I was clear about one thing — that I want to put all my energy in my work so that the work speaks for itself.”

Having lived in India for three decades, Yuriko is still in awe of the simplicity of life she observes here. She says, “In Japan, everything looks as if it is behind a cover, a curtain of sorts. Here, even if you are in a car you are not distant from the people running a tea stall on the roadside and vice versa. Even if people do not know of each others’ life, they co-exist, a quality I greatly respect.”

Along with her artworks, Yuriko has been writing about her Indian experiences for many Japanese journals and is planning to soon begin writing a book.

Yuriko believes that her artistic sensibilities have broadened in India. “In Japan, most of the art was driven by context which set limitations for an artist. When I saw Bhuta figures in Delhi’s Crafts Museum I was taken aback. I was in awe. I realised what we were missing in Japan. If you are too fixated on context you lose something which is meaningful to humankind. The strength the artwork displayed was beyond any comparison. I am happy for the choice I made to move here.”

Today, Waswo is pleased with his Indian art experience but hopes for better funding for local museums. He says, “The history of Indian art is rich and deep and can hold its own against any other country. The biggest problem is having this fact receive the recognition that it deserves, and a lack of proper museum structure within the country is the chief problem. What is most needed is a meaningful investment in art infrastructure.”

Incidentally, it was again a visit to Delhi’s Crafts Museum that led the American artist and professor Kathryn Myers on her ambitious exploration of Indian art forms. “I had no particular interest or knowledge about Indian art prior to coming here for the first time in 1999. Perhaps because of that I had no prejudices, assumptions or expectations. I was floored the first time I entered the Crafts Museum in Delhi, I was powerfully drawn to the works there and wanted to know everything I could about them, and that research led to so much more. I was also very interested in modern art and it helped me learn more about the episodes in Indian history that inspired it as well as insights about western prejudices, such as that Indian art was merely “derivative” of the West. When you are first “in love”, as I was with Indian art, you can’t get enough. I read extensively and attended exhibitions whenever I could,” says Myers, who also works as a professor of art at the University of Connecticut.

Myers spends lot of time here, studying Indian art and imagery. She is a regular visitor primarily due to her Fulbright fellowships in 2002 and 2011. She plans to spend six months in India every year post her retirement (in five years or so), and hopes to set up a studio space here. Her ongoing video project is called Regarding India, where she has interviewed some leading personalities in contemporary and modern Indian art.

“I travelled a great deal on my first visit. It amazes me now how many places I visited. There is a ‘vibe’ this place has. The capstone of my first visit however was Varanasi, which was mythic in my imagination and has remained one of my favourite places in India,” says Myers.

Myers spends lot of time here, studying Indian art and imagery. She is a regular visitor primarily due to her Fulbright fellowships in 2002 and 2011. She plans to spend six months in India every year post her retirement (in five years or so), and hopes to set up a studio space here. Her ongoing video project is called Regarding India, where she has interviewed some leading personalities in contemporary and modern Indian art.

The exposure to, and understanding of, Indian art led Myers to develop a course on the subject which she teaches at the University of Connecticut. She says, “The influences of Indian art and culture on me have extended from my own work to my students and university community. I have had the opportunity through my university to curate two major museum exhibitions of Indian art and I started teaching a course on Indian art. The subject matter of my work — paintings and photographs — is drawn from Indian architecture and I’ve also created a series of short videos of devotional practices that I use in my course. One of them is Auspicious Sight, which is all sound and images, from when I was staying in Varanasi. It’s more similar to my paintings in how it frames space, movement and subtle sounds.”

Myers’ connection to India has shaped her own approach to painting. She says, “Before I came to India I was making very large figurative painting based on Catholic or Biblical imagery. Both the scale and subject matter of my work changed greatly once I came to India. Perhaps I was influenced by miniature paintings or maybe it was the necessities of travel, but I was more drawn to a humble scale of the miniature than the very large canvases. The medium changed from oil to opaque watercolor. Most of what I’ve learned about India has been triggered by art.”