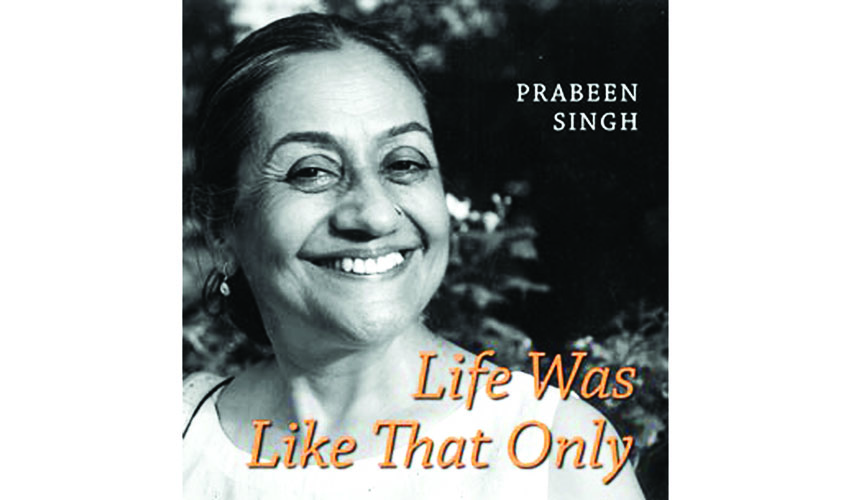

Life Was Like That Only

Author: Prabeen Singh

Publisher: Academic Foundation

Pages: 400

Price: Rs 595

In her book of memoirs, Life Was Like That Only, Delhi-based author Prabeen Singh gives a heady account of an eventful life as lived by someone who is part of the earliest generations of a newly independent India.

Born in Jamshedpur, Singh recalls how the city benefited from the social largesse of the Tatas: recalls Beldih club’s swimming sessions; weekend movies at the Golmuri club; how, while growing up she was influenced a lot by the songs of Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, and so forth. She recalls being brought up in a Sikh family where tradition existed in accomodation with liberal ideas.

Singh writes of a father who began giving lessons on alternative history after having learnt how teachers at school were likening Aurangzeb to the evil, intolerant Mughal ruler who had killed Teg Bahadur. She writes of her grandfather who had built the Sikh National College in Lahore and was its principal till Pakistan became a reality (the college was built to eradicate the spectre of communal divide and inculcate a sense of national pride for an independent, undivided India as it was also the first college in India to fly the

tiranga).

But that nation-building had its fair share of negative fallouts is noticeable in her poignant descriptions of how her family had to relocate from Jamshedpur to Old Delhi in the wake of Partition, and how she then sensed a sort of disorientation because of differences in cultures, food, languages, people, and so forth. Singh’s family was forced to sever familial bonds and shift to Delhi as her father was invited to join the National Building Organisation, a semi-autonomous agency of the Government of India.

The prelude to a strong-willed, independent life, as exemplified by Singh’s central role in organisations like Stree Sangharsh and Saheli, had been set during her formative years in her grandfather’s elder brother, Master Tara Singh’s house in Amritsar. That was where she got introduced to the ideals of Akali Dal leaders and learnt about their fight for a linguistic plebiscite in order to protect Sikh identity in a Hindu majority area. She also got to know of the reign of terror under Pratap Singh Bhairon who would force Punjabi Hindus to claim their mother tongue to be Hindi and deny reservations to Dalits who had converted to Islam and Sikhism.

Mid-way in the book, we are introduced to the ignominy of the 1962 war: how all women during the Sino-Indian conflict were handed with rough wool to knit socks and pullovers and caps for the brave soldiers facing the heavily armed Chinese army and how it never reached them and was rumoured to have been sold in the bazaars of Calcutta (the Indian Army fought in the snow in khaki PT shoes). It took the Army almost a year to obtain a comprehensive list of Indian soldiers and officials held in Chinese prisons. Singh writes about a friend of her father’s, Colonel Balwant Singh, and the tales he’d recount to her family of the kind treatment and care meted out to war prisoners like himself by Chinese doctors and other officials.

While history is always invoked to target Indian communists for betraying patriotic sentiments and supporting the Chinese in the war, Singh’s account of the first official anti-cow slaughter campaign in 1966 becomes a scathing indictment of such politics as propunded by Hindu nationalists. Singh writes, “A bleaker side of the RSS, and the largest show of Hindi chauvinism, was however the anti-cow slaughter campaign in 1966… When Prime Minister Indira Gandhi rejected their demand, a mob of approximately 10,000, led by the Naga sadhus, clothed only in ash at their splendid naked best, surrounded Parliament House along with hundreds of cows. Prevented from entering Parliament, the mob rampaged through the city and the first 48-hour curfew was ordered… We of course learnt too that cows could be effective tools of protest.”

Prabeen Singh writes various episodes from her life with a tint of wicked humour, interlinking them with historic events. Particularly mentionable is her recount of the rise of Naxalism during her college years at the Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi and how the capital city became an unwilling host for a lot of hippies around that time but sadly, their utopian notions of India’s all-inclusive spirituality became a matter of tragic exploitation by local pushers, pimps and cheap hoteliers in Paharganj and that the closest they could get to their beliefs was visiting a gurudwara for a langar.

Misconstrued notions of a Naxalite, as a jholawallah romantic hero fighting for the oppressed of rural India, which existed among Prabeen and her friends as college kids were to be seen persisting even in her husband, years later, when during their divorce settlements, one of the conditional clauses set by him was that Singh could not have a live-in jhola-swinging boyfriend. Laughable as it may sound in this context, it is sadly how left-leaning activists are perceived even today and quite often their activism is credited or discredited on such grounds!

After her divorce, Singh writes how earning a living was no longer an option but a necessity, the reason she joined NORAD (Norwegian Organisation for Aid and Development) which necessitated her travelling to remote villages of Bihar, UP, Bengal, Odisha and Rajasthan. This determination to merge individual identities with the larger collection of “our kind of people, our dream India” had its germination during her days as a gender rights activist — bringing to the attention of mainstream media the custodial rape of a tribal girl in 1972 in Mathura, working for the rehabilitation of the victims of Trilokpuri during 1984 riots.

Life Was Like That Only has the structure of a journal — in terms of its format as also the non-linear narrative pattern of contemporary socio-historic events (from Partition to Babri Masjid demolition) that have been recreated from the author’s memory — and may not immediately appeal to lovers of fiction. What may certainly come as a respite are the 100-odd black and white images presented here, which have been culled from personal albums and public domains.