Claude McKay’s novel Romance in Marseille deals with queer love, postcolonialism and the legacy of slavery. It also complicates ideas about the Harlem Renaissance, writes Talya Zax.

Claude McKay’s novel Romance in Marseille could hardly sound more contemporary. A black man, Lafala, loses his legs as a result of his white captors’ cruelty, then, in a striking allegory for reparations, receives a compensatory windfall. He takes his new fortune from New York to Marseille, a hub of the African diaspora, and plans to return to West Africa in hopes of undoing his colonial education and reintegrating in the village of his birth. Meanwhile he lives in a sexually liberated working-class milieu, where queer love is accepted as a fact of life, no more subject to judgment than its heterosexual counterpart.

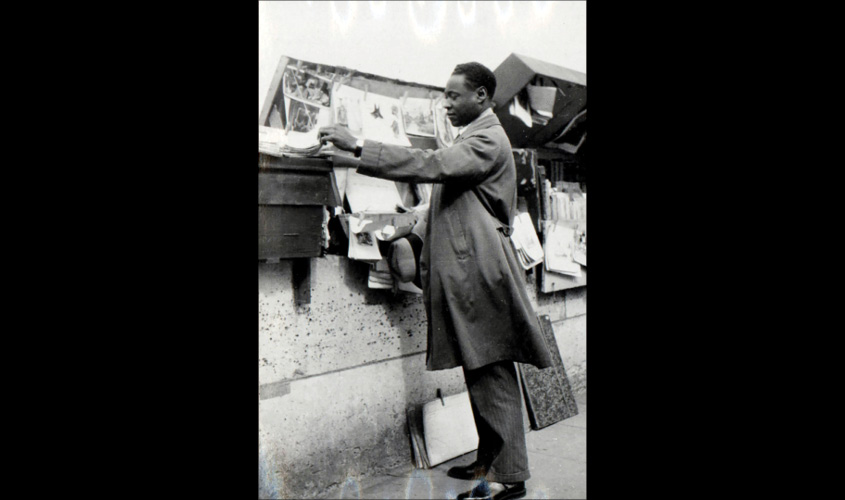

The book’s themes—queerness, the legacy of slavery, postcolonial African identity—are among those at the forefront of literature today. But McKay lived from 1889 to 1948 and was a central figure of the Harlem Renaissance. Now, a century after that movement began, Romance in Marseille will finally be published for the first time Tuesday. Its debut coincides with recent shifts in thinking about the Renaissance, which is increasingly seen as grappling not only with race but also with class, gender, sexuality and nationality.

Romance in Marseille, published by Penguin Classics and edited by Gary Edward Holcomb and William J. Maxwell, is the second of McKay’s posthumous novels to appear in recent years, after the 2017 publication of Amiable With Big Teeth. McKay began writing “Romance in Marseille” in 1929 and put it aside in 1933. It was a practical decision; McKay earned his living from writing, and his editor, Eugene Saxton, who had previously challenged sexually transgressive passages in his books, believed that Romance in Marseille was too shocking to sell.

“He’s writing about the underclass,” said Diana Lachatanere, who oversees McKay’s literary estate through the Faith Childs Literary Agency. That subject placed McKay in conflict with gatekeepers of literary Harlem and specifically W.E.B. Du Bois. It’s no surprise that Romance in Marseille, perhaps McKay’s most complicated examination of marginalized economic and social classes, couldn’t find a publisher during his lifetime. (“Who’s running publishing houses?” Lachatanere asked. “Very staid middle-class people.”) While the novel is in some ways dated, it still, today, feels radical.

“In recent years, we have taken a much more expansive look at the Harlem Renaissance,” said Venetria K. Patton of Purdue University, who coedited the 2001 anthology Double-Take: A Revisionist Harlem Renaissance Anthology. “The race narrative is still

Why? During the Renaissance, mainstream narratives of the movement were shaped by its complicated relationship with white readers. The Renaissance was made economically possible partially through the patronage of wealthy white individuals like Charlotte Osgood Mason and could therefore be constrained by their interests and their prejudices. Led by figures like Du Bois, many of the Renaissance’s participants saw the movement as a way to address white audiences and encourage them “to reevaluate black lives as being equal,” according to Jean-Christophe Cloutier, co-editor of Amiable With Big Teeth. Efforts to redirect the movement to black audiences, and to write about a wider array of concerns, were largely relegated to the Renaissance’s queer subculture.

McKay belonged both to that subculture and to the movement’s mainstream. His 1928 novel Home to Harlem was the first American bestseller by a black writer. But despite being seen as one of the Renaissance’s guiding lights, McKay—Jamaican, bisexual, a Marxist who grew disenchanted with communism before the rest of his cohort—also brought an outsider’s critical gaze to the movement. He was concerned not only with whom their target audience should be but also with how they depicted class politics, particularly in a queer context.

Maxwell, one of the editors of Romance in Marseille, notes that the novel’s most overt gay characters include a black female prostitute and “a dock worker socialist white male stud.” That was a remarkable departure from conventions of the Renaissance, in which most queer relationships were depicted in “a genteel context of gay male instruction,” as Maxwell put it.

Holcomb, the book’s other editor, pointed out that Romance in Marseille depicts great freedom in working-class queer life. “The queer characters are not portrayed as being exotic or subcultural,” he said. “They’re just ordinary working people.”

McKay’s vision of a black cultural movement that transcended national, class and sexual barriers was not unique. Several of his contemporaries who similarly challenged the Renaissance’s norms have also experienced recent revivals. Two novels by Ann Petry (including The Street, her revolutionary novel of black, female working-class life) were reissued by the Library of America in 2019. Jeffrey C. Stewart’s 2018 biography The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke brought renewed attention to the other most significant gatekeeper of the Renaissance, looking specifically at the influence of his queerness.

There Is Confusion, by Jessie Redmon Fauset, the longtime editor of the official NAACP magazine The Crisis, whose work was often disregarded because of her gender, is being reissued Tuesday, the same day Romance in Marseille will be released. And two previously unpublished books by Zora Neale Hurston have come out in the last two years.

More may be coming. Cloutier stumbled on the forgotten manuscript of Amiable With Big Teeth while studying at Columbia in 2009. The two manuscripts of Romance in Marseille, held by Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and Yale’s Beinecke Library—the Penguin Classics edition is based on the later Schomburg manuscript—have long been known to scholars, but copyright conflicts and a lack of market interest prevented the book’s publication.

As archival research accelerates and 1920s-era writing is freed from copyright restrictions—this year, works from 1924 came into the public domain—it’s likely that more rediscovered works are on the way. Cloutier recently worked with the Beinecke to locate an uncataloged collection of manuscripts by Petry.

And archived manuscripts aren’t the only available source of material. Marlon Ross, an English professor at the University of Virginia, has his eye on black newspapers of the era including The Chicago Defender and The New Amsterdam News. “A lot of these published poetry, short stories—all kinds of materials from people who we don’t remember,” Ross said.

Our sense of the Harlem Renaissance, Holcomb said, is growing to encompass “something much more complex and broader than the original idea” of “a cultural nationalist African American movement.”

Romance in Marseille, one of the Renaissance’s most radical texts, hidden for decades from public view, makes a natural avatar for that development. “What McKay wanted,” Holcomb said, “was something much more deeply revolutionary.”

© 2019 THE NEW YORK TIMES