Stepping into Serendipity Arts Festival would mean chancing upon an India that has remained elusive to you, that you have kept your mind shut from and have failed to explore beyond the comfortable walls of your urban existence. Did you think Indian puppetry was just about the Rajasthani kathputli? Or classical dance was just about the big green-faced Kathakali from Kerala?

“Our younger generation is disconnected from art forms. But in a festival like this, you can smell and taste the flavor in some form. You have to make that time for the arts. This festival takes it to children, to the streets, the market place. And that’s when you have the new and the old meeting. An older audience for younger forms of art, a young audience for older forms of art. This is what opens up minds,” says Leela Samson, a Bharatanatyam exponent and dance curator for Serendipity Arts Festival 2018.

Located in Panjim, the capital of Goa, the festival takes inspiration from the spirit of the city, the freshness of the sea breeze that still manages to infuse a fading Portuguese culture in the Konkan mainstream of today’s Goa.

This is where you see the Shakespearean tragedy Othello performed by Kathakali dancers from Kerala, their dramatic eyes and facial movements keeping pace with the narrative of an overtly suspicious protagonist who ends up murdering his wife.You learn about the mould-breaking grand dame of Kathak, Kumudini Lakhia, through a lyrical tribute paid to her on stage by Kathak dancers. How encompassing is India, in not just absorbing foreign art forms, even those of our colonisers, but also becoming their only living showcase in the whole world. A costal folk dance of Portuguese origin called Chavittu Natakam talking about European victories of King Charlemagne—which has been lost in Europe but is alive in India. A politically and socially vocal form of folk dance which came to prominence during the Peshwa rule but makes the boldest statement on cross dressing today. Anil Hankare’s troupe of Lavani dance where male dancers dress up as women in Maharashtrian Kashta sarees and regale the audiencewith their bawdy sentimentality.

The force behind this celebration is Chairman of Hero Enterprise and Founder of Serendipity Arts Festival, Sunil Kant Munjal. “If we look back a few hundred years ago, Indian arts was in this manner, all of it played together and it was part of everyday life. Our architecture, our furniture, our textiles, our food—all of it has an amazing amount of creative content—which is both native Indian and carries influences of our colonisers. The philosophy of the Serendipity Foundation—art around us never has a unitary focus, there are multiple influences that play all the time. That’s how are art forms used to be. What we currently have is inheritance from British times, of Western sensibility where theatre is separate, music is separate and art is separate. This is not our form. We follow an amalgam of arts. And this is what we have set out to do. The energy that gets generated at the junction of different art forms is worth experiencing.”

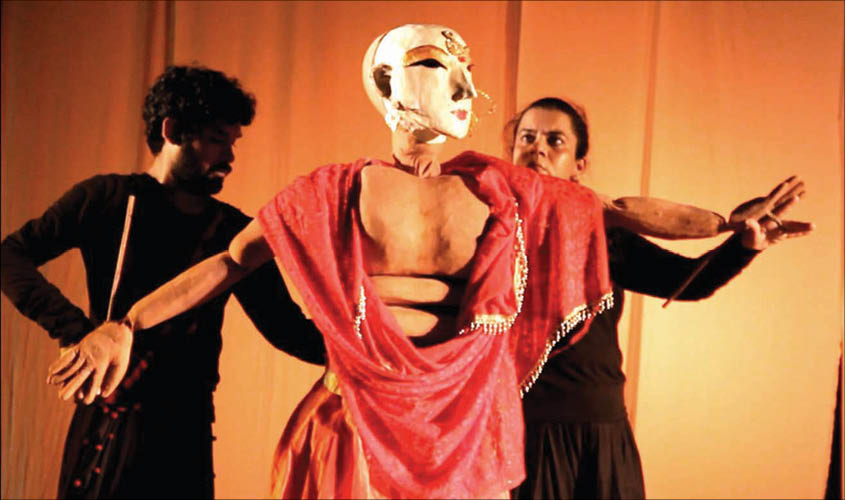

In theatre, the ever-fascinating epic of Mahabharata gets a re-look through Anurupa Roy’s retelling of it. Roy uses the narrative of the Sillakeyata, a hunting community in Karnataka’s Hassan and Madya region.“I wanted to stay true to the Mahabharat which is spoken in the leather shadow puppets tradition which talks about the back story of each character. Like Shakuni didn’t just wake up and decide to be the bad guy. This not just looks at characters in black and white butmakes them more real. Yudhishtir, at the end of the day is a gambling addict. We have to accept it. He is one the best kings to have but makes the worst decisions when his addiction takes over.”

In her retelling of the Mahabharata, puppets are allowed to be become intense, gut-wrenching and alive. Unable to say when a life size marionette blends into the shadows of leather puppets, and when the English speaking narrative moves into live singing in Kannada, explaining the nuances of an incident. LED stage lights are used to highlight sculpted masks in the foreground but the background remains shrouded in the mystery created by traditional oil lamps. The war scenetakes elements from the martial form in Chhau dance. Gandhari’s curseon Krishna for the death of her 100 sons morphs into a costume drama with Gandhari dressed in a white shroud splattered with red and strung with the heads and limbs of her sons. The final punch to this dramatic puppet epic comes with a light-hearted remark from the young woman narrator on stage explaining the audience about the core message of Mahabharat – When will we ever learn that war never did us any good!

Sahar Zaman is an independent arts journalist, political newscaster and curator;

more on her work at www.saharzaman.com