Croatian writer Dasa Drndic is often described as a blend of Beckett, W.G. Sebald and Thomas Bernhard. But these comparisons don’t throw any light on her singular talent, writes Parul Sehgal.

This month, Merriam-Webster named the pronoun “they” its word of the year. Runners-up included “quid pro quo,” “impeach” and, for good measure, “egregious”—as thrifty a description of 2019 as we could hope for.

But what if lexicographers did us the favour of not only anointing words but annually retiring a few that have been embraced too exuberantly and look a little shabby for it—a little dazed to find themselves miles from their original meanings.

“Witness” (as in “the act of witness,” “bearing witness” and all its vacant subsidiaries) would be high on my list. A complicated notion has been breezily

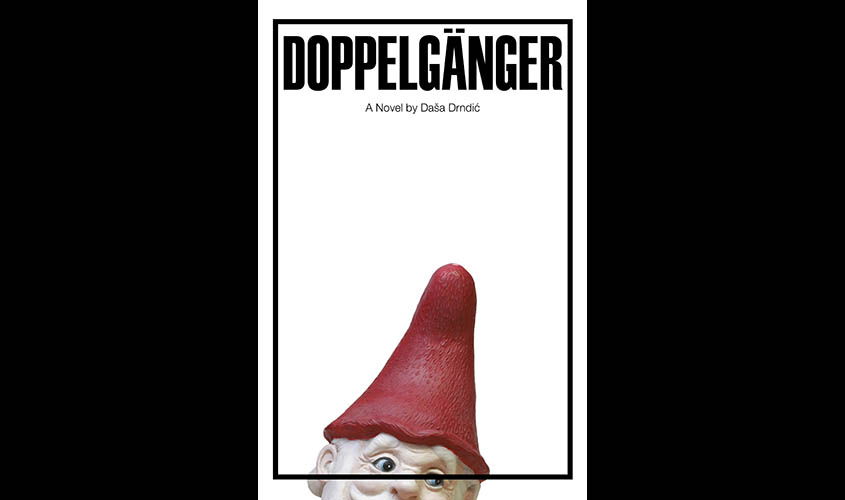

I had forgotten how great the cost could be when I came (shamefully late) to the gory, majestic work of Croatian novelist Dasa Drndic, who died last year at 71. Fewer than half of her 13 novels have been translated into English, many with the scrupulous care of Celia Hawkesworth. The linked novels Belladonna and EEG have recently been published, along with Doppelgänger, an earlier work, her favourite of her novels—this “ugly little book of mine,” she joked, wondering if it was too repulsive for readers. (S.D. Curtis co-translated Doppelgänger with Hawkesworth.)

Drndic is often described as a blend of Beckett (for the bleakness and rhythms), W.G. Sebald (the reliance on photographs and interest in historical amnesia) and Thomas Bernhard (first-rate misanthropy), but these sorts of comparisons do nothing to convey the singular experience of reading her work.

This writer does not tell stories; she had flagrant contempt for them—those cozy bourgeois tchotchkes that belonged to a safer time, when retreat from the political was permissible. Her books are contraptions intended to produce a series of psychological and somatic responses in her readers. In short: panic, pity, shame, nausea, exhilaration—and then, the bewildering desire to experience these very emotions again.

These are not books to be read but endured. I resumed all my old vices to survive them, and adopted a few new ones. I developed warm, fraternal feelings for Job. “Art should shock, hurt, offend, intrigue, be a merciless critic of the merciless times we are not only witnessing but whose victims we have become,” Drndic once said. She wanted her rhythm and repetition to “irritate,” and struck any flourishes that might “sweeten” the prose. She wanted her novels to feel like a punch in the stomach. The books frequently open with a startling image, something frightening, but also quite funny or gently obscene—an old man registering the fullness of his diaper, in Doppelgänger. It’s as if the writer is testing us. Are you game? she seems to ask. Or are you the type to flinch from reality?

For much of her career, her great subject was the former Yugoslavia’s unacknowledged role in the Holocaust, the butchery of the fascist Ustasha puppet state established by the Nazis. (Drndic’s father was a leader of the anti-fascist movement.) “In Germany and Austria, almost 70 years after the end of the war, ever new serials of undigested Nazi trauma keep appearing,” Drndic’s alter ego Andreas Ban laments in Belladonna. “In Croatia, in a patriotic trance, Ustasha crimes and their perpetrators dress up in carnival robes of rotten nostalgia, their descendants keep quiet or lie about their fathers’ and grandfathers’ pasts.”

The characters in her novels, however, give themselves over to voluptuous grief. Complicity rots them from within. Andreas Ban immures himself in his apartment on a mission to amputate his memories, trying to forswear speech, and even thought, while his body goes to ruin with breast cancer, hemorrhoids, glaucoma. In Doppelgänger, a man spends his life cutting little holes in his shoulders, belly and thighs with a pair of nail scissors. He attempts to return his family’s silver to the original Jewish owners and ends up, like so many of Drndic’s characters, killing himself. He rams his head into an iron door.

Damage to heads, mouths, lips are common in these novels. So too are references to asthma, lung disease and cancer, pulmonary obstructions. Drndic’s fondness for commas gives her sentences their peculiar gasping quality. The characters choke on what they cannot, will not, say.

Sebald once counselled against depicting horror too directly, particularly where the Holocaust was concerned. “We’ve all seen images,” he said, referring to the concentration camps, “but these images militate against our capacity for discursive thinking, for reflecting upon these things.” They “paralyze, as it were, our moral capacity.” To tell such stories effectively demanded a degree of canniness and obliquity to sidestep reflexive responses and surprise readers into fresh feeling and seeing. In Drndic, however, everything is depicted bluntly and head-on: the children condemned to die at the Ustasha camps, covered in flies and trailing their own intestines.

Everything is to be faced. While being treated for cancer, Drndic told critic Eileen Battersby how “fascinated” she was by the pain radiotherapy produced in her bones. When she knew she was dying, she threw herself a farewell party at a favourite bookshop.

This desire for directness is best exemplified by the obsession with naming that runs through her novels. In Trieste, the narrative is interrupted by a 40-page list that names the Jews who met their deaths in Italy or were deported to camps from Italy between 1943 and 1945. One of Drndic’s British publishers recalled a London event at which a copy of the book was passed around and the audience told to tear out pages on which they recognised a name—“the book lost its form, as a society does when an element is removed.” In Belladonna, a list names the 2,061 Jewish children sent to camps from the Netherlands between 1938 and 1945. In EEG, she lists chess players exterminated by the Nazis or lost to suicide.

Detail, story, selection are traits that Drndic grew to disdain as her work grew ever more demanding and diffuse. She made a ethic of sprawl and amplitude. In her final work, EEG, Andreas Ban, who once refused speech, refused memory, allows himself to be inhabited by ghosts of history and his family. The narrative no longer belongs to him—did it ever?

“Maybe none of us has his own life,” Drndic once wrote. “Is your life unconditionally yours?”

© 2019 THE NEW YORK TIMES