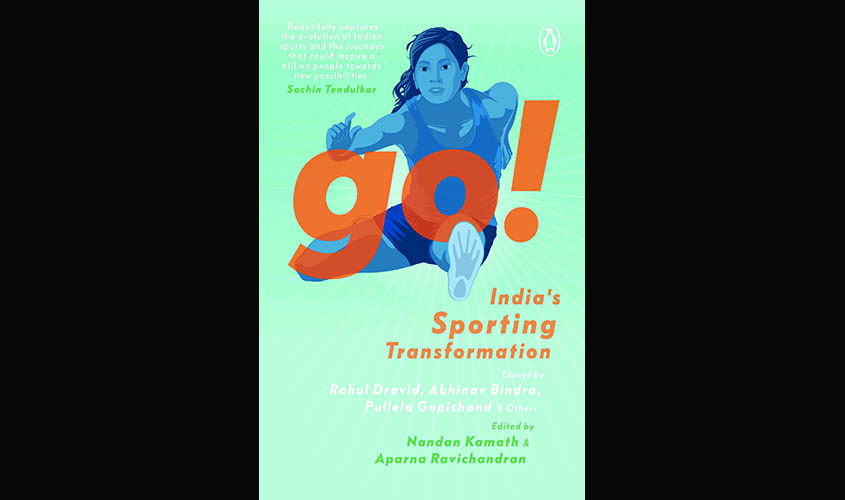

In this essay, excerpted from the new anthology Go!: India’s Sporting Tranformation, sports writer Sharda Ugra looks at how the modern Indian athlete has emerged as an individual with a voice.

Mid-July 2018, when this chapter was way past its many deadlines, an exchange around Indian sport on social media became, to use mobile app language, a notification for our times. “Our” here is Indian sport—that baffling, exhilarating, frustrating, impossibly optimistic entity—and the Twitter exchange around it indicated that some straitjacketed conventions had been pulled apart.

It took place just after Hima Das kicked in her afterburner across the straight in the 400-metre final at the IAAF World U20 Championships (also called the World Junior Championships), becoming the first Indian to win a track gold medal at a world event. After her successful semi-final run, the Athletics Federation of India (AFI) had commented on a video clip of Das’s trackside interview on its Twitter handle saying, “#HimaDas speking to media after her SF win at #iaaftampere2018 @iaaforg Not so fluent in English but she gave her best there too. So proud of u #HimaDas Keep rocking & yeah, try ur best in final![sic]!”

Edited by: Nandan Kamath, Aparna Ravichandran

Penguin Ebury Press

Pages: 312

Price: 299

After the gold, the AFI Twitter handle was pelted by a hailstorm of censure for commenting on Hima’s English. The ruling body of Indian track and field athletics was called a “loser” and hauled up with responses of “shame”, “disgusting”, told that they should concentrate on finding talent rather than teaching English, and accused, among other things, of trying to “belittle her glory”. To such a degree of ferocity, that the AFI had to apologise on the social network service, doing so in Hindi. A rough translation of the apology read, “We merely wanted to show that Hima is fearless, whether on the track or outside. Despite being from a small village, she spoke freely with the foreign media. We apologise again to those who were angry.”

Apologies, it must be pointed out, do not come easily to sports federations in India. That would mean the admission of an error and accountability to someone other than themselves. That doesn’t happen enough—neither the governors of an Indian sport admitting errors, nor feeling the need to be accountable. While the AFI’s Hindi version of an apology sounded more sardonic than heartfelt, there was no denying that the ruling body had been stung by the very public backlash.

Ten years ago, no Indian athlete, particularly one from outside cricket, would have found such a public outcry against their treatment by their sports federation. What was remarkable about the furore over Hima Das and her fluency in English was that the support came from an unknown multitude. They pounced upon the AFI’s condescension and turned the narrative in a previously unexpected direction. Rather than Hima being conscious of her English from now on (the athlete herself said she wasn’t offended, and admitted, in an interview to India Today, that her English “isn’t that good”), the people behind the AFI’s social media handles were put on guard. What used to be the modus operandi around Indian athletes (those outside the cricketosphere) in the hands of those above them in the hierarchy of authority is now off-limits.

In a decade of seismic changes in Indian sport—in the breadth of competition, range of success, elite athlete management and the variety of journalism—the involvement of the general public in an otherwise quiet world has been visible and, in many cases, such as Hima Das’s, loudly heard.

Until around the early years of the 21st century, larger India paid attention to these athletes once every two years—when either an Olympic Games or an Asian Games came along. They were recognised and feted by their sporting community and the media working around it, but not the masses, nor the country’s business community.

Other than a few engaging, and it must be emphasised, English-speaking, personalities—such as Indian tennis player Leander Paes, chess maestro Viswanathan Anand, and the snooker and billiards men Michael Ferreira and Geet Sethi through the 1990s—the rest tended to be clumped together under a category considered uncool. The English-language press and media largely fed this general trend, and while they did not have the weight of readership or viewership numbers, they controlled the attention of the corporate cash-dispensers available to sport.

In a conversation about picking a cover photograph for a national news magazine, the image of Indian hockey’s inspirational, inflammable Dhanraj Pillay in a resplendent turban was turned down because he looked like a gavaar (a yokel), and it wouldn’t go down well with the magazine’s English-speaking readership. The fact that the majority of athletes fundamentally came from either rural or working-class backgrounds and homes of scarce financial means in many ways controlled how their lives and stories were told to the rest of India.

At that time, communication also travelled in a straight line—from the sport via the journalist/reporter/writer/ television reporter to the reader/viewer, with the athlete’s voice often found at the far end of it. Sports media until the mid-1990s was made up of newspapers and magazines, and stories about an athlete’s success or struggle could only be found there. Information about the athlete without English, at the very start, came from their coaches or the officials who had a grip on the futures of both athlete and coach.

Athletes who wanted to tell their own stories were often considered difficult and troublesome. In a team sport, such as hockey, it was the tempestuous Pillay or goalkeeper Ashish Ballal. Amongst individual athletes, it is hard to name anyone who spoke even little English and protested against or questioned authority through the early 1990s. Michael Ferreira never held back with his English and the one exception to all rules was Prakash Padukone, who led a rebellion against the Badminton Association of India in 1997. Success in an individual sport could provide an athlete some attention and leverage, but it tended to be limited. The athlete as a free agent was a concept that did not exist in India at the time—it is only being recognised today.

The tribe of mostly independent individual athletes was to be found in tennis, motor sport or golf—Leander Paes turned pro in 1991, Narain Karthikeyan’s first racing season in the UK was in 1993, Jeev Milkha Singh set out on the European tour in 1998. The rest of the athletes, however, stayed connected within the official superstructure that Indian sport is built around. This meant that government funding and official approval became the underlying basis of their career paths. Athletes were seen, but rarely did we hear them. Never mind rocking the boat, even suddenly standing up on deck was not recommended.

Extracted with permission from ‘Go!: India’s Sporting Tranformation’, published by Penguin Ebury Press