Pullela Gopichand is a one-man army who has transformed Indian badminton like never before. Under his stewardship, India’s best shuttlers led by P.V. Sindhu and Saina Nehwal, with an Olympic silver and a bronze tucked under their belts, are gearing up to fire at Tokyo 2020. In a free-wheeling interview with Utpal Kumar, India’s chief national badminton coach talks about the transformation of Indian badminton, his equation with Sindhu, and of course India’s chances at the 2020 Olympics.

You are being credited with transforming Indian badminton. How do you see that journey? And what all went into making India a badminton superpower?

For me, to begin with, badminton wasn’t a career as such. I just loved to play it as a kid. Back then in Hyderabad we never thought badminton was big because if you look at the 1990s Andhra Pradesh would be fourth or fifth state in the South Zone. Andhra was never a sporting state. So, for me to think about becoming a national champion was also a big thing. But as and when I moved ahead to become a state champion I set my eyes on the national, and when that was achieved too, I started looking at the international level.

For us, Prakash (Padukone) sir, who had won All-England Championship, was a player from another planet. So, step by step I realised what all I could achieve. By the end of my career, after I had three knee surgeries—in 1994, 1996 and 1998—and after a lot of learning from my coaches, I thought I knew the formulae to win. But unfortunately, I didn’t have the body to take the rigour to win internationally. By the year 2002 I had another surgery —fourth one—on my right knee. It was followed by multiple fractures on my foot. It was then I realised my days as a badminton player were over. Since I couldn’t use the formula in myself, I picked up a bunch of kids in Hyderabad to coach them. I realised I would be better off as a coach rather than a player. This realisation led me to move into coaching young kids. I had my own share of problems but there has always been someone to help me, whether it’s the government, the federation or individual players.

When did you realise that your coaching academy had actually taken off?

I always had this belief that it would work. And Saina (Nehwal) was the first one to join, followed by others led by (Parupalli) Kashyap. So, I could see players with whom results could be achieved one by one. I just wish we had a system in place which is more autocratic in nature and where I could do everything I wanted, we could have got far more better results. A lot of young talents would have benefited from such a tough regimen and that would have helped them focus on fitness and strength, both mental and physical.

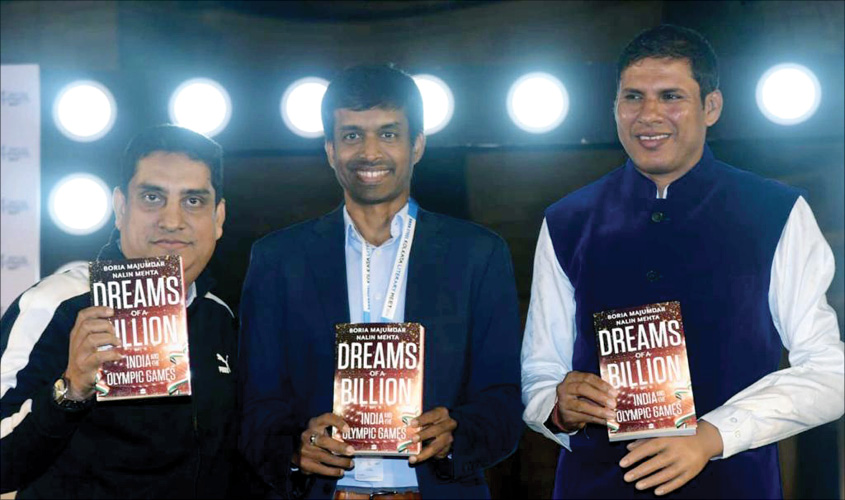

Boria Majumdar writes in his book Dreams of a Billion that you actually took away P.V. Sindhu’s phone and also instructed her to learn to scream hard. How more ‘autocratic’ do you want to become (laughs)?

(Smiles) I am talking from a systemic perspective, and not from an individualistic point of view. I could make a different only to those players with whom I was directly involved. But there were many more talents waiting to be tapped. We could have had more talents if we had a strong system in place.

You are a soft-spoken person, how difficult is it for you to become so ‘autocratic’ as a coach?

As a player I was always very aggressive. I believe as a player it is a much-needed attribute for success. Aggression brings a killer instinct in a player and helps one seize the opportunity at the right time. And as a coach also one needs to have the confidence to say what needs to be said assertively. For me, a player’s performance is paramount. So, I do whatever it takes to get the best out of a player.

Do you ever feel bad that you have become too harsh on your players?

If I were playing, I would have been harder on myself. The days when I was a player, I was very unforgiving on myself. That’s what I expect from players and from champions—a relentless pursuit to excel on the field. As Abhinav (Bindra) puts it, the Olympics doesn’t come once in four years, it comes every day. As a coach and a player, we need to believe this. It’s our everyday efforts that make the success at the Olympics possible.

You saw the potential in Sindhu very early, as early as 2010. What did you see in her that made her a champion player she is today?

It’s first and foremost genetics. She has a great physicality. I think she is one of strongest athletes on the court. And she has a knack of delivering at the biggest tournaments. Though there can be criticism that she did lose some matches at the highest level, she has been very consistent. Sindhu has in her to win at the biggest tournaments. But for me her physicality and strong stroke play attracted initially. But what caught my attention in a big way was when she was 17 and we went for a tournament in China where she beat the then Chinese Olympic silver medallist. She overcame the fear to win against her in China and that also at the young age of 17. That moment gave me the confidence that Sindhu can excel at the highest level.

You are a great fighter. You hate losing. What went into your mind when Sindhu lost the Olympics final at Rio in 2016?

For me, the win at the semis was big because it got us a silver at the Olympics. Before the final, I told her to focus on winning, but once she lost, I went up to her and told that she should not think that she lost a gold but that she won the silver. I think that perspective is important. To win a silver Olympic medal was a huge achievement. I decided to focus on the positives rather than dwell on losing.

What are India’s chances in the Tokyo Olympics?

Last few months have not been great for Indian badminton. But each of our players who is going there has a chance of winning a medal. We have a good preparation going into the Olympics. And whenever we had good preparations in the last 10 years we had done well at the Games. I hope it continues in Tokyo.

How important is a medal to you?

Yes, a medal is important. But the job of a coach is to keep things simple and tidy, rather than on medals. Anyway, player already knows the importance of winning a medal. Everyone wants to win one.

The moment a player wins a medal at the Olympics, there’s excessive hero worship. How do you see it?

These are things that are a sad reality in Indian sports. I do believe that the ecosystem needs to be more mature for us to handle champions. The moment there’s too much of a hero worship we kind of miss the point that sports is bigger than anything else. That’s the bottom line.

In India, our focus often is confined to sports infrastructure and, at best, individual sportspersons. Is that a right approach?

No, it’s not a right approach but this government has done well to change the way we look at sports, whether it’s through Khelo India or university games. It’s a different language and a language in the right direction to transform India into a sporting nation. Also, the culture in India is changing where playing sports is not a bad thing anymore. We are now looking at sports positively.

Coaches in India don’t get enough credit and respect. Do you think so?

I have been fortunate enough to get the respect and recognition, but how many coaches in India get this? We, as a nation, need to address this, whether it’s about coaches or teachers. Unless we celebrate them, I don’t think we would be able to get the best people to take up the profession.

You always believe in preparing for the future. How do you see the future of Indian badminton?

I am very happy that the government, for a change, is not just focusing on the 2020 Olympics but also the next and the one after that. It’s a step in the right direction. Otherwise, we would have just talked about Tokyo—and just that. I believe to think about Tokyo is already too late. It is, therefore, the right time to focus on 2024 and 2028.