Ranked among the great modernists of Bengal, Benode Behari Mukherjee was born with partial vision and later in life went completely blind. A new retrospective shows us how the artist drew strength from his weaknesses, writes Bhumika Popli.

A good exhibition often leaves you with many profound thoughts. One such show is the ongoing retrospective of Benode Behari Mukherjee (1904-1980), aptly titled Between Sight and Insight: Glimpses of Benode Behari Mukherjee. The exhibition consists of more than 100 artworks which are spread across the two Delhi branches of Vadehra Art Gallery.

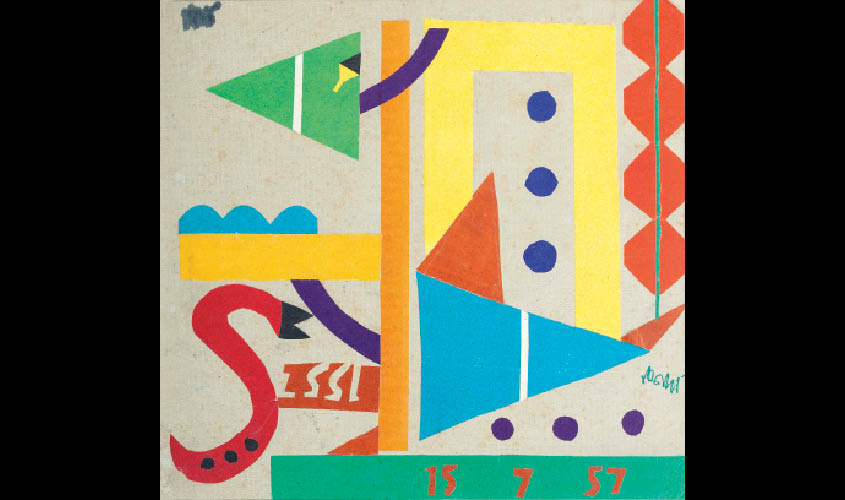

As a child, Mukherjee was blind in one eye and myopic in the other. But later in life, when he was 53, his condition went from bad to worse—from partial sight to complete blindness—after a botched eye operation.

But Mukherjee didn’t let his disability come in the way of his artistic practice. The Delhi show also has on display paper cuts, fabric collages and the image of a mural he made post his blindness. At this time, he also taught art history at Santiniketan’s art faculty, Kala Bhavan, of which he had been one of the first students.

Satyajit Ray’s film on Mukherjee’s life, entitled The Inner Eye, is also a part of the exhibition. The film documents Mukherjee’s creative process after he had lost his vision completely. In one of the scenes, he is shown measuring the scale of the paper and estimating the proportions of the figures by using his hands.

Mukherjee was also an award-winning writer. He once wrote, “Blindness is a new feeling, a new experience, a new state of being.” Early in his life, Mukherjee was an aloof child, keeping his distance from society and spending most of his time around nature.

At 13, when he was sent to study art at Santiniketan, the casual atmosphere of this school and the rural landscape surrounding it, worked in his favour. Besides, he was taught by the distinguished artist Nandalal Bose, who further helped Mukherjee heighten his artistic sensibility.

Mukherjee’s early sketches, landscapes and figurative pieces from the ’30s to ’50s, contain dense line work. From this period his watercolour paintings, too, depict sharply defined lines and boundaries. But his style underwent a major shift 1950s onward. As his eyesight got weaker, his faith on line work began to diminish. Instead, he started giving more attention to rich and vivid colours.

Mukherjee’s murals form an important part of his artistic trajectory. In his murals he has depicted student life in Santiniketan, a village scene in Bengal, a religious procession he saw in Nepal and more. Late in life, he made a mural using paper cuts and ceramic tiles.

What many critics consider his most important work is also a mural, entitled Life of the Medieval Saints. It was painted in 1946-47 and depicts Bhakti saints. R. Siva Kumar, curator of the show, who also teaches at Visva-Bharti University in Santiniketan, says, “The tradition of ethico-religious thoughts as articulated by the Bhakti saints who rose from a humble strata of society and merged back into its wide stream is its theme. Represented as a pageant of life moving across three walls it is monumental in scale as its theme is epic in vision.”

Mukherjee’s ability to perceive the contemporary society made him a true modernist. Kumar calls Mukherjee “a self-reflexive artist”. According to Kumar, Mukherjee is a modern Indian artist because he questioned what it is to be an artist in a given context of time. Mukherjee himself was living in a transitional period, when India was moving from being a traditional society to becoming a modern one.

Kumar’s interpretation applies just as well to Mukherjee’s self-portraits. Kumar says, “Self-portraits have always been there, you look into the mirror and you paint yourself. But Mukherjee is actually imagining himself in his self-portraits. He is thinking about his inner identity. He fairly understood his limitations.”

In one of Mukherjee’s paintings, called Artist in Studio, which was made in 1933-35, we see a human figure leaning over what looks like a sketchbook. “He actually had to bend down to paint because he couldn’t see clearly from a distance,” Kumar says. “This [what’s depicted in Artist in Studio] is a highly dignified way of showing oneself. Everything around him, the artist’s tool, the chair, the table and other objects, are painted in meticulous detail. It shows us that these things are painted with care and empathy which further demonstrates the kind of person he might be. In the painting, he is almost self-effacing but he doesn’t allow you to enter his space, you can visually look at him but there are impediments in your way. The chair, table and other objects block your movement. So he is someone very private and we also see him sitting at the threshold between nature and the house, which further depicts his personality.”

‘Between Sight and Insight: Glimpses of Benode Behari Mukherjee’ is on view till 22 February