US-based journalist’s book reveals how coordinated Dhaka and U.S. efforts, combined with India’s strategic moves, forced Bangladesh Prime Minister Hasina to flee to India.

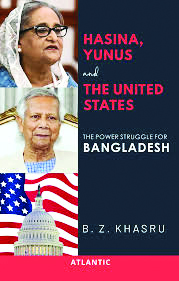

New Delhi: B.Z. Khasru, a U.S.-based journalist, through his book, “Hasina Yunus and the United States: The Power Struggle for Bangladesh” (Atlantic Publishers & Distributors) released earlier this month has brought to public domain the circumstances that led to Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina being forced to feel to India in what was the culmination of efforts of multiple Dhaka and U.S based actors to remove her from power.

Khasru, who has written two books before this, spoke to The Sunday Guardian. Edited excerpts.

Q: How did the U.S. leverage its diplomatic, economic, or political tools, including Yunus’s connections with the Clinton Global Initiative and U.S. policymakers, to support Yunus or undermine Hasina?

A: American affiliates of Grameen Bank had been working with the Clinton Foundation’s Clinton Global Initiative programs as early as 2005. Grameen America, the bank’s nonprofit U.S. flagship, which Yunus chaired, had “given between $100,000 and $250,000 to the foundation.” Bank spokeswoman Becky Asch stated that the amount reflected the institution’s annual fees to attend the foundation’s meetings. Another Grameen entity chaired by Yunus, Grameen Research, had donated between $25,000 and $50,000. As a U.S. senator from New York, Hillary Clinton, along with then-Massachusetts Senator John Kerry and two other senators, sponsored a bill in 2007 to award the Congressional Gold Medal to Yunus. Two former American secretaries of state, George Shultz and Madeleine Albright, also called on Hasina to back off. Many other world dignitaries backed Yunus as well. Irish billionaire Richard Branson and Paul Volcker, former Federal Reserve chairman, were among global leaders who urged Hasina not to seize control of Grameen. In addition, 32 members of U.S. Congress wrote a similar open letter. In a startling turn of events, the Congressional Bangladesh Caucus turned against Hasina’s government, even though the caucus was intended to work to improve Dhaka-Washington ties. It warned her that relations were under a cloud because of Yunus’ dismissal. Twenty-six members of the U.S. Congress, an unusually large number for such an initiative, signed the letter and told Hasina that “we respectfully urge you to resolve this matter with Yunus through a mutually satisfactory compromise that ensures the ongoing independence of Grameen Bank.”

Q: Why do you think Narendra Modi chose to support Sheikh Hasina, and how critical was Modi’s backing in stabilizing Hasina’s rule and countering U.S. support for Yunus?

A: Of the two major political parties in Bangladesh, India perceived Hasina’s group as more reliable and friendly. The BJP placed the BNP — the other major group headed by Khaleda Zia — on the enemy list because two of its cabinet members were believed to be involved in arms smuggling to rebels in the Northeast. India informed Zia about this, but she denied that her ministers had aided the insurgents. She really had been unaware of it; however, India concluded that Zia had known it and deliberately lied. When Hasina returned to power, she denied any support to the rebels, which Modi highly appreciated. He was also pleased with the transit agreements. India’s support to Bangladesh helped reduce U.S. pressure on Hasina, but did not directly influence the public perception of Yunus, who was rejected by Bangladeshis as a serious politician in 2007. Bangladeshis care more about how India’s policies affect their welfare and whether Delhi will fairly treat them.

Q: How significant was Hillary Clinton’s involvement in promoting Yunus, and what impact did her actions have on Bangladesh’s political landscape?

A: Hillary Clinton was a strong supporter of Yunus. Whenever Yunus faced problems with Hasina, he sought Clinton’s help. The U.S. Embassy in Dhaka did, indeed, intervene with the prime minister on behalf of Yunus. During a visit to Dhaka in May 2012, Secretary Clinton expressed her support for Yunus. “I don’t want anything that would in any way undermine” the micro-lending bank. “I have followed the dispute over Grameen Bank from Washington, and I can only hope that nothing is done that in any way undermines the success of what Grameen Bank has accomplished,” Clinton told a public question-and-answer session in Dhaka. “I highly respect Muhammad Yunus, and I highly respect the work that he has done, and I am hoping to see it continue without being in any way undermined or affected by any government action.” In September 2009, Melanne Verveer, the first U.S. ambassador for Global Women’s Issues, informed Hillary Clinton that Hasina was stalling Grameen initiatives: “See if you can find a way for me. I invite you to be a peacemaker! Otherwise, it will become explosive for nothing,” These were the words of Yunus as read by Verveer to Clinton from his email.

Q: How do you compare Bangladesh’s military’s political role with that of Pakistan, considering their shared historical legacy?

A: Bangladesh’s military lacks any ideological or spiritual links with Pakistan’s military. Compared to the Pakistani military, the Bangladeshi armed forces are highly political due to their roots in the Liberation War. Their political views stem from their perception of India’s role regarding Bangladesh. The military is divided into three segments: ordinary soldiers, mid-level officers, and the top brass. Rank-and-file troops tend to be religious and traditional, reacting negatively to perceived or real anti-religious government actions. However, they have very little say in which direction the country or the military should move. The mid-level officers are the backbone of the military. These officers are religious yet modern, coming from the middle class and shaping military policy. India’s policies toward Bangladesh greatly affect them and middle-class Bangladeshis in general. They want Bangladesh to manage its own affairs independently and expect a fair and equitable relationship with Delhi. The top brass, unlike Pakistani generals, often concede to mid-ranking officers. Unlike Pakistani soldiers, who do not question their commanders, Bangladeshi officers articulate their desires, sometimes with guns.

Q: How would you describe the relationship between Sheikh Hasina and Muhammad Yunus before their fallout? Did Sheikh Hasina perceive Yunus’s rise as a threat, and what were the key events that escalated their conflict?

A: Hasina had suspicions about Yunus since he won the Nobel Prize in 2006. Soon after receiving the prize, Yunus began criticizing politicians as corrupt. However, for political reasons – to win over influential people—Hasina supported him, promoting his small-loan program. Yunus had formed negative impressions of his father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, soon after his return home from the United States, if not earlier. He regarded Major Ziaur Rahman, who announced Bangladesh’s independence, as a hero, not Mujibur Rahman. Zia became president after Mujib’s assassination and created the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, a rival of Hasina’s Awami League party. Yunus soured on the Awami League because Dhaka University did not give him the job he wanted upon his return from the United States in 1972. During a famine in Bangladesh in 1974, he urged the head of Chittagong University, Professor Abul Fazal, to chastise Mujib for the people’s suffering. Later, Yunus sided with the BNP and worked with the military-backed interim government to remove Hasina from politics. In addition, he threatened the Awami League, stating that more than 8 million Grameen Bank members, who represented nearly 25 percent of Bangladesh’s voters when considering their family and friends, were not just citizens but also voters, meaning they could influence elections against Hasina.

Q: What evidence supports the claim that the U.S. influenced Sheikh Hasina’s removal in 2024?

A: Washington’s estrangement from the Awami League has a long history. After Hasina returned to power in 2009, U.S. Ambassador Dan Mozena told reporters in Dhaka, “The U.S. interaction with the sitting government is not business as usual.” He stated that U.S. aid to Bangladesh would continue on a case-by-case basis. In other words, the Obama administration was simultaneously appeasing and ramping up pressure on the Hasina government to align it with Washington’s geostrategic interests in curbing China’s influence in the region. In 2014, in the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing, Nisha Desai Biswal, the assistant secretary of state for South and Central Asia, called for new elections in Bangladesh to accommodate the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, led by Hasina’s rival, Khaleda Zia. In February 2019, a bipartisan group of six influential U.S. Congress members urged the Trump administration to address “threats to democracy” in Bangladesh. They noted allegations of election fraud, rigging, and voter suppression in the 2018 polls and pushed Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to “take action.” Earlier, a top Pentagon commander fumed over the elections, stating Hasina “is trying to achieve a de facto one-party rule.” In 2021, Washington sanctioned multiple Hasina administration officials and members of security forces for alleged human rights violations. Washington announced that anyone attempting to taint the upcoming elections would face a U.S. visa ban. This intimidated officials into disobeying Hasina’s orders and created a maelstrom, allowing the re-emergence of radical Islamic groups. In September 2023, the State Department disclosed that it had taken steps to impose visa restrictions on Bangladeshi individuals responsible for, or complicit in, undermining the democratic election process in Bangladesh.

Q: Was the military’s refusal to act against protesters influenced by external factors, such as pressure from the U.S.?

A: Many military officers and government officials had been intimidated by U.S. sanctions and recent visa restrictions. The U.S. punitive measures followed a 2021 Al-Jazeera television program, alleging corruption against powerful political and military figures, including Army Chief General Aziz Ahmed.. In 2022, Khalil published a report in a Sweden-based news portal, alleging that Bangladeshi officials unlawfully detained and tortured innocent dissidents. He claimed that he had been tortured by the military in a secret detention center during a previous interim administration, leading to his taking refuge in Sweden. At least two of the individuals involved in these TV programs — David Bergman and Tasneem Khalil — received money from Human Rights Watch and provided information from Dhaka. Much of the data used by the U.S Treasury Department to sanction Bangladesh came from Human Rights Watch, based in New York.

Q: To what extent do you believe Yunus acted as a proxy for U.S. interests in Bangladesh?

A: Yunus became a founding member of the board of Grameen Foundation in 1997 and served until 2009. He has been an emeritus member since then. The United States Agency for International Development, an arm of the U.S. State Department formed a partnership with Grameen Foundation in 2009, giving loan guarantees of $162.5 million “to support more low-income individuals and small businesses with microloans, as a pathway out of poverty.” The U. S. anti-poverty initiatives were started in the 1950s to counter communism. Back in the 1990s, Badruddin Umar, a leftist academic in Dhaka, called Yunus a CIA agent. In recent years, there have been periodic rumours that Washington wanted to create a military base on Saint Martin’s Island in the Bay of Bengal to contain China. Hasina made this allegation, too, but the U.S. denied it. Since Yunus took over, the island has been sealed off to the public, ostensibly to save the environment, but critics charge it was the precursor to handing over the strategic land to the United States.

Q: Could the U.S. efforts to back Yunus be compared to its regime-change tactics in other nations?

A: There had been allegations that the United States sought a regime change in Dhaka. In March 2011, Yunus’ supporters formed human chains in many places in Bangladesh after Hasina’s government had removed him from Grameen Bank. This was intended to foment unrest to overthrow Hasina, as had happened in Egypt, Libya and Ukraine, where street movements orchestrated from abroad ousted elected leaders. Pranab Mukherjee, then External Affairs minister, was advised by Secretary Clinton that India should support Yunus. She suggested that Hasina would be an unreliable partner for India and that New Delhi should distance itself from the prime minister and support Yunus as the potential head of a national or technocratic government.

Q: Why did Hasina consider Yunus’s proposed Grameen expansions as attempts to consolidate power?

A: She thought that Yunus, who had been working to expand his business empire, could someday emerge as a powerful political rival, so she needed to cut him down before it was too late. Yunus had a deal with Harvard University to start Grameen Medical College in Bangladesh to train doctors to treat the poor. Grameen partnered with the Nike Foundation, Bayer, and a university in Glasgow, Scotland, to open three nursing colleges. With a lamentable state of nursing, Bangladesh had one nurse for every three doctors. Yunus sought Grameen’s partnership with GE Healthcare to produce medical equipment for in-home calls by rural healthcare workers. Hasina acted against Yunus because she was concerned about his influence in rural Bangladesh. The majority of the Awami League’s support came from the grassroots level, an area where Yunus had helped millions improve their lives. The poor would support those who had made a difference in their lives.

Q: How did the alleged Hindu favouritism and quotas under Hasina’s government impact public perception?

A: For many years, rumours have circulated in Bangladesh that Hasina had imported numerous Hindus from India to fill top civil service positions to ensure loyal Awami League supporters were in the administration. The omnipresence of Indian businesspeople in Dhaka greatly fueled this view. Ordinary people asserted that they often saw these “imported Hindus” in the media serving as government spokespersons yet speaking in a dialect different from theirs. Hindus, who comprise 8 percent of Bangladesh’s population, held 12 percent of civil service cadre officer positions in 2017. They occupied only 3 percent of these jobs in 2001 when Hasina ended her first term as prime minister. The data clearly reveal that the number of Hindu civil servants started to rise after Hasina returned to power in 2009. This occurred due to job quotas for the freedom fighters. No concrete figures are available, but the proportion of Hindus among the freedom fighters is likely greater than their demographic ratio. This is so because 80 percent of the refugees who went to India in 1971 were Hindus, many of whom fought in the Bangladesh Liberation War and later received preference in civil service jobs under the quota system. Anti-Hasina elements twisted this phenomenon to falsely accuse the prime minister of giving jobs to her supporters (meaning Hindus), an accusation that incited the unsuspecting common people against her. In Bangladesh, Hindus are often equated with India, even though they are natural-born citizens. In addition, Hasina was widely regarded as India’s lackey and a darling of Hindus, who allegedly often sacrificed national interests to appease Delhi. The Hasina administration failed to effectively counter this growing public perception.

Q: What role did India play in countering U.S. efforts to back Yunus, as reported by sources like Pranab Mukherjee?

A: Pranab Mukherjee, India’s former president, who also served as External Affairs Minister before becoming head of state, had strong personal ties to Hasina since her days in exile in New Delhi after her father’s assassination in 1975. Mukherjee, a Bengali himself, rebuffed a demand from Hillary Clinton for India to support Yunus. Mukherjee expressed his full confidence in Hasina. Soon, Hasina caught wind of the plot from her sources in Washington, and she phoned Mukherjee. He assured her that India would stand by her. As External Affairs Minister, he championed the interests of Bangladesh and his protégé.

Q: Did India’s support for Hasina strengthen her ability to counter domestic political challenges?

A: India’s commercial support helped Hasina pacify people, especially because it reduced power shortages and prices of essential commodities. It also generated goodwill for India. However, people perceived India’s support as inadequate. Since Bangladesh won independence, the public perception has been that India benefits more from Bangladesh than it contributes. In other words, India helped create Bangladesh to exploit it. Persistent killings of Bangladeshis at frontiers, water-sharing issues, transit facilities through Bangladesh, the construction of seaports, high tariffs, the illegal migrant issue, and border fences are some of the nagging matters that have fostered negative perceptions.

Q: Why did the military leadership pivot from supporting Hasina to tacitly enabling Yunus’s rise? Did Pakistan’s history of military coups influence Bangladesh’s military’s decision to intervene or retreat in political crises?

A: All indications suggest that the military sealed Hasina’s fate on Sunday night (4 August) when it refused to comply with her order to impose stricter security measures to suppress the violent agitation. The anti-Hasina stance of the mid-level officers, who declined to order the soldiers under their command to shoot the agitators, was leaked out to the demonstrators. This information emboldened throngs of people to take to the streets the following day. This was an undeclared coup d’etat, a betrayal from Hasina’s point of view. There was a widely circulated rumour in Bangladesh that Army Chief General Waker-Uz-Zaman held a virtual meeting with his field commanders the night before Hasina’s removal. During the meeting, the commanders informed the general they would not order the soldiers under their command to shoot the protesters to end the street demonstrations. There were also reports that two days earlier junior officers had already expressed concerns about being asked to fire on civilians in a meeting with the Army chief. The chief became virtually powerless, but it remains a mystery if he kept this information secret from the prime minister, denying her precious time to formulate her new moves. The next morning, around 11 o’clock on 5 August, when Hasina asked military and police chiefs why they could not control the mobs, they told her the demonstrations were too massive for the security forces to suppress. They also advised her that the violent protesters could reach the prime minister’s palace in 45 minutes and that she must leave immediately to save her life.

Q: Your book suggests that the removal of Sheikh Hasina was not solely due to student protests but was also backed by deep-rooted religious-political cliques. Could you elaborate on who these factions were and their motivations?

A: When Bangladesh fought for independence in 1971, pro-Islamic parties opposed it. They had been suppressed, and Hasina banned the theocratic Jamaat-e-Islami. Its members infiltrated the military and student organizations, becoming the most ardent opponents of Hasina. They were backed by Jamaat from underground. Another group that worked against Hasina was pro-China. They wanted an independent Bangladesh, but felt that their homeland had become a vassal state of India. Many military officers also hold this view, so they want stronger ties with China to counterbalance India.

Q: How did the issue of job quotas for freedom fighters and the alleged favouritism towards Hindus become a tool for anti-Hasina forces?

A: The demand for the quota reform was merely a facade used to incite public sentiment aimed at toppling the prime minister. The civil service comprises only 1.6 million jobs within a workforce of 73 million, and more than 400,000 candidates vie each year for fewer than 4,000 available positions, representing just one percent. Thus, these jobs logically cannot be a significant issue for the vast multitude of job seekers, even though the allure of prestige and employment security may exist. The real issue was the belief that the Hindus held far more of these positions than their share of the population justified. The agitation, which started with a simple demand to repeal a special job allocation policy that allegedly favoured ruling party followers, suddenly transformed into a mass ultimatum for the prime minister’s resignation. The dynamics of the protest shifted even though Hasina had accepted the protesters’ demands earlier. The issue the students were apparently fighting against resulted from a court ruling; it was not Hasina’s doing. In fact, the Hasina government sided with the students and fought the court ruling. The court had ruled in favour of the quota beneficiaries, the Liberation War veterans and their children, who belonged in disproportionately large numbers to the Hindu community, which became highly visible to ordinary Bangladeshis.

Q: The military’s refusal to impose stricter measures and their reported communication breakdown with Hasina seems pivotal. Was this a coordinated move against her, and who might have influenced it?How credible is the claim that the military’s decision to defy Hasina’s orders was part of an undeclared coup d’état?

A: Bangladeshis fear the army, which means they obey military orders. If the military wanted, it could have prevented mobs from entering major sensitive areas of the city and government installations. The mobs were emboldened by the leaked information about the army refusal to shoot them. The agitators suddenly switched their demand and called for Hasina to resign, while accelerating their ultimatum to storm the prime minister’s official residence. The army chief was powerless because of the field commanders’ refusal. If he ordered them to shoot the demonstrators, he would have been defied. On the contrary, if he informed Hasina about the refusal, he would face dismissal and sedition charges, as happened in 1996 when President Abdur Rahman Biswas fired Army Chief Lieutenant General Mohammad Nasim for defying an order. Caught between a rock and a hard place, Army Chief General Waker-Uz-Zaman sided with his field commanders and decided to remove Hasina.

Q: You have compared Muhammad Yunus’s rise to power to Mussolini in Italy. Do you see parallels between their paths to power, and what does this say about the state of democracy in Bangladesh?

A: Ordinary folks in Bangladesh view elections as festivals. They love to vote in elections, and democracy begins and ends there. For urban elites, democracy means self-enrichment. As long as the system serves individuals, it’s nice and dandy. Hardly anyone considers how their actions might hurt others. This attitude is prevalent among members of the upper class. People in Bangladesh often question each other’s patriotism. After Hasina fled to India, a former professor of Dhaka University commented that she had gone to “her country.” Very few in Bangladesh accept the fact that complex problems require complex solutions, which necessitate effective political structures. They favour a strong commander and quick solutions. They tend to be easily duped by politicians. Political reform ideas hastily crafted by the current regime will not work because they are deeply flawed. Elections will be held, new governments will be formed, but political unrest will continue to resurface. However, well-researched plans can be developed to improve things if people are included in the process. However, democracy will be elusive in Bangladesh for now.

Q: Why do you think Sheikh Hasina made the decision to flee to India rather than rally her supporters to demonstrate her strength on the streets?

A: There were rumours that Hasina wanted to go to her home district but was refused by the security chiefs. Her request to record an address to the nation was also denied. Some people speculated that if Hasina had succeeded in rallying her supporters, a civil war could have ensued. The military sought to prevent such a situation, so they forced her to go to India. Furthermore, Hasina had very little time to consult with her well-wishers and decide the prudent course of action.

Q: How did Yunus gain support from protesters and factions to ascend to power, despite not having a political mandate?

A: Yunus was chosen because he was most visibly acceptable to the people. The situation was similar to the one that followed the assassination of Hasina’s father, Sheikh Mujib. After the young officers killed him, they realized that both the people and the military would reject them as rulers. So, they selected Khandaker Moshtaque Ahmed because he was known as a pro-West, anti-India figure . After Hasina’s downfall, the military concluded that Yunus would be favoured by the demonstrators and anti-Hasina political groups, while the United States would also welcome him. The military likely assumed India would support him, too, as the generals did not encounter resistance from Delhi, which readily agreed to grant Hasina refuge.

Q: You have suggested Hasina’s tenure brought significant economic progress to Bangladesh. How should her economic achievements be evaluated in light of the political turmoil?

A: History will accurately judge Hasina’s economic achievements. During her fifteen-year rule, Bangladesh’s economy expanded fivefold, the best record in Bengal’s history. Some hard-core anti-Hasina individuals desperately sought to diminish her performance, but the world recognized the economic wonder that Bangladesh was under her leadership . Since Bangladesh’s independence, Western news media invariably used the phrase “one of the world’s poorest countries” whenever they mentioned Bangladesh. Only during Sheikh Hasina’s rule did The Wall Street Journal feature a four-column headline declaring: “Bangladesh ‘Basket Case’ No More,” and Goldman Sachs described it as an Asian “economic tiger.”

Q: You have mentioned that the Yunus administration could be declared illegal. Do you believe this could happen, and what impact might this have on Bangladesh’s political stability?

A: This occurred during the administrations of Moshtaque and Ziaur Rahman, whose actions were nullified by the Supreme Court. Zia anticipated this possibility and had parliament pass a law allowing his actions to be altered through a referendum. However, the Supreme Court voided most of his actions and retained only those necessary for the continuity of the government.