The war in Gaza has given Iran the opportunity to showcase the capacity of its newly restructured network of allied militias, or proxies, which together demonstrate Teheran’s strategic reach.

I never expected to reach this age, so I am living on borrowed time”, said Saleh al-Arouri, the deputy leader of Hamas just days after the terrorist group’s bestial rampage on Israeli citizens on 7 October. “It’s not strange for the commanders and cadres of the movement to be martyred”, he continued in an interview with Beirut-based AL-Mayadeen, the pan-Arabist satellite news TV channel.

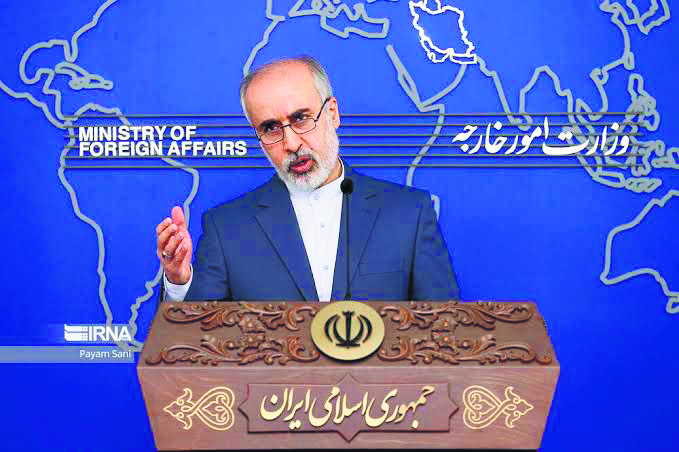

Last Tuesday, Arouri’s prophetic words came true. His “borrowed time” was up when an Israeli drone struck Hamas’ offices in Dahiyeh, an area in Beirut’s southern suburbs which is also a stronghold of the Iranian-backed Hezbollah, killing him and three other members of the terror group. In a chilling response to the attack, Iran’s Foreign Affairs spokesman, Nasser Kanaani, declared that “martyr’s blood will undoubtedly ignite another surge in the veins of resistance and motivation to fight against Israel”, leaving many to wonder if the much anticipated escalation of the three-month conflict will now happen.

Tuesday’s explosion in Beirut came after more than two months of heavy exchanges of fire between Israeli troops and Hezbollah along Lebanon’s southern border with Israel. Hezbollah is by far a more formidable foe for Israel than Hamas. With up to 150,000 missiles, many of them precision guided and able to reach any target in Israel, together with about 100,000 fighters, Hezbollah dwarfs Hamas in both size and sophistication. Many Hezbollah troops have also been battle hardened by fighting in Syria. Hezbollah also enjoys a close relationship with Iran, which gave it life in 1982 and which views it as a proxy.

The war in Gaza has given Iran the opportunity to showcase the capacity of its newly restructured network of allied militias, or proxies, which together demonstrate Teheran’s strategic reach, while allowing it to keep a distance from the fight. Take a look at events in the region and you’ll see that on almost any given day Iran’s allied militias have carried out an attack somewhere in the Middle East. Not only is Hezbollah engaged in daily exchanges of fire with Israel across the border, but Iran’s proxy in Yemen, the Houthis are targeting ships in the Red Sea, while its proxy in Iraq, Kata’ib Hezbollah, and other Iraqi groups are hitting US bases in Syria and Iraq. These proxies present an axis of resistance to Israel, orchestrated and supported by Teheran.

Arouri’s assassination on Tuesday came four years almost to the day after the killing of Qasem Soleimani on 3 January 2020 by a US Reaper drone strike near Baghdad’s International airport. Soleimani was the much revered commander of Iran’s Quds Force, and was personally responsible for the country’s extraterritorial and clandestine military operations. He almost single-handedly cultivated Iran’s proxy militias and in the process achieved a mythical stature that far exceeded his formal rank. Following Soleimani’s death and also that of Kata’ib Hezbollah’s leader, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, who was also assassinated at the time, the axis of resistance fell into disarray as fierce rivalries erupted.

Enter Hezbollah’s Hasan Nasrullah, the most senior figure commanding the oldest and most successful battle- hardened group, who began to play a leading role in Soleimani’s footsteps. Nasrullah emerged as the official spokesman for the axis of resistance and is considered as the first among equals. Using subtle mediation, he re-formed the axis and implemented a new strategy called the “unity of fronts”, in which all three groups would take action if one of them is attacked.

So, when Hamas carried out its brutal attack on Israel and Netanyahu’s government declared war on the terrorist group, carrying out fierce battles for the control of the Gaza Strip, Hezbollah enlarged its activities on Israel’s northern border and Yemeni Houthis increased their attacks on western shipping in the Red Sea. Nasrullah’s new strategy fits well with Iran’s objectives, as now Teheran can assert its regional influence by arming, funding and inspiring its proxies without necessarily triggering a major incident that could draw its own forces into battle. Without giving them direct orders, Iran is able to leverage its proxies in a below-the-radar battle against the West, Israel and its neighbouring Sunni Arab States, a benefit which has already tarnished the Abraham Accords, currently hanging by a thread, and scuppered the long-awaited security deal between Israel and Saudi Arabia. A big win for the Mullahs.

On the flip side, however, there are dangers that a miscalculation in any of the areas of conflict could escalate into a full-scale war, which nobody appears to want. There exists a real fear in the region that a series of apparently unconnected events could cause the bloody and brutal war in Gaza to spill over into a much wider and more consequential conflict, drawing Iran into direct conflict with Israel and the US.

That nerves are on edge was evident on Wednesday when, a day after Arouri’s assassination, two explosions killed nearly 100 people and wounded scores at a ceremony in Iran at the event to commemorate the fourth anniversary of the assassination of Qassem Soleimani. Iranian officials quickly blamed unspecified “terrorists”, and the US rushed to tell the world that their intelligence undoubtedly indicated that ISIS and not Israel was to blame. This was later confirmed by the Islamic State. Both the US and Iran clearly wanted to avoid the incident resulting in an escalation of the Gaza conflict.

Yet there is some evidence that Israel would actually like a confrontation with Iran to have it out “once and for all” with their existential enemy. This would force Iran to respond decisively, which in turn would bring the US into the combat. For their part, the Iranian leadership has been very careful not to be drawn into the conflict directly, evidenced by their reaction to assassinations in Syria and Southern Lebanon.

In other words, Teheran has clearly shown that it wants to engage Israel on its own terms using proxies, rather than on Israel’s terms.

The major current concern, however, is the activity of Yemeni Houthis in the Red Sea. One aspect of the axis of resistance is that members do not necessarily act on the direct orders of Iran, only with the agreement of Iran. The Houthis’ attacks against international shipping in the region pose a strategic threat to the West’s economy. Instead of passing through the Red Sea, ships have to take the considerably longer route around Africa, thus increasing costs. Iran insists that it has not directed the attacks against ships, but no-one doubts that Teheran could stop them if they wanted. The Houthis would have no choice but to stop their action as they are entirely dependent on Iran for both political and military support.

The war in Gaza, which at the current rate will last well into 2024, and the various incidents around the Middle East, patently show that Iran wants to maintain coordinated activities against Israel by the use of the axis of resistance, rather than having an all-out conflict with Israel. For all the bluster coming out of the country, Iran has shown remarkable restraint and rational calculations since the beginning of October. Teheran’s plan is for a prolonged series of low intensity attacks in the Middle East by its proxies in Lebanon, Iraq and Yemen, so that the long-term costs to the US and Israel remain high.

It remains to be seen whether Israel’s patience will snap if Iran’s strategy is successful. As former Israeli leader Naftali Bennett so memorably put it: “it’s not enough to keep hacking at the tentacles of the octopus. You need to hit its head”.

John Dobson is a former British diplomat, who also worked in UK Prime Minister John Major’s office between 1995 and 1998. He is currently Visiting Fellow at the University of Plymouth.