What prompts the negative sentiment towards India across British society, spanning from parliamentarians to media outlets? Could this perhaps be attributed to a lingering colonial legacy, an inability to view India as a partner rather than a former subject?

LONDON

Recent developments have positioned India as the world’s fifth-largest economy, surpassing the UK’s standing, and it has also beaten Russia, the United States and China in their efforts to be the first to land a spacecraft near the South Pole of the moon. The landing of Chandrayaan-3, where craters hold frozen water, may well be the first step towards humanity’s future and an insight into its very beginning. Amidst this landscape, given India’s G20 presidency and the imperative for new trade avenues, alongside the significant presence of our 1.8 million-strong Indian diaspora, there is a real sense of now or never for optimising trade and cooperation with India.

India’s burgeoning global economic status coincides with its role as a pivotal ally in the strategic challenge presented by China’s ascendancy. The Chinese Communist Party’s explicit drive to cultivate a China-centric international order favouring its authoritarian paradigm has far-reaching implications, compromising individual rights and liberties. The strategic imperative of countering this Chinese trajectory resonates both in Western defence priorities and within India’s own policy framework.

India is reinforcing diplomatic, economic, and security ties with Southeast Asian nations, a concerted effort aimed at balancing, hedging against, or directly counteracting Chinese influence. Notably, New Delhi’s provision of a naval warship to Vietnam and the training of Vietnam Air Force personnel stand out as recent markers of this strategic direction. An avenue relatively unexplored is China’s territorial borders, China pushes into the Himalayan region much like it pushes into the South China Sea. To miss deepening security and defence relations between the UK and India to this end may well be a very serious opportunity missed indeed.

However, a legacy of colonialism plagues the UK-India relationship, marring the UK approach with an air of superiority and a false sense of “knowing”. This, if unchecked, could potentially undermine the prospect of fostering a genuine partnership with India—a must for post-Brexit Britain.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s commitment in 2021 to elevate UK-India ties was a step in the right direction. It encompassed doubling bilateral trade and facilitating migration for economic and professional reasons. Yet, despite India’s discernible trajectory as a strategic partner, high-ranking UK parliamentarians let Boris’ early rapport spoil, with Suella Braverman voicing reservations about the prospective trade agreement on the grounds that it might do the thing Boris was positive to support, increase Indian immigrants into the UK.

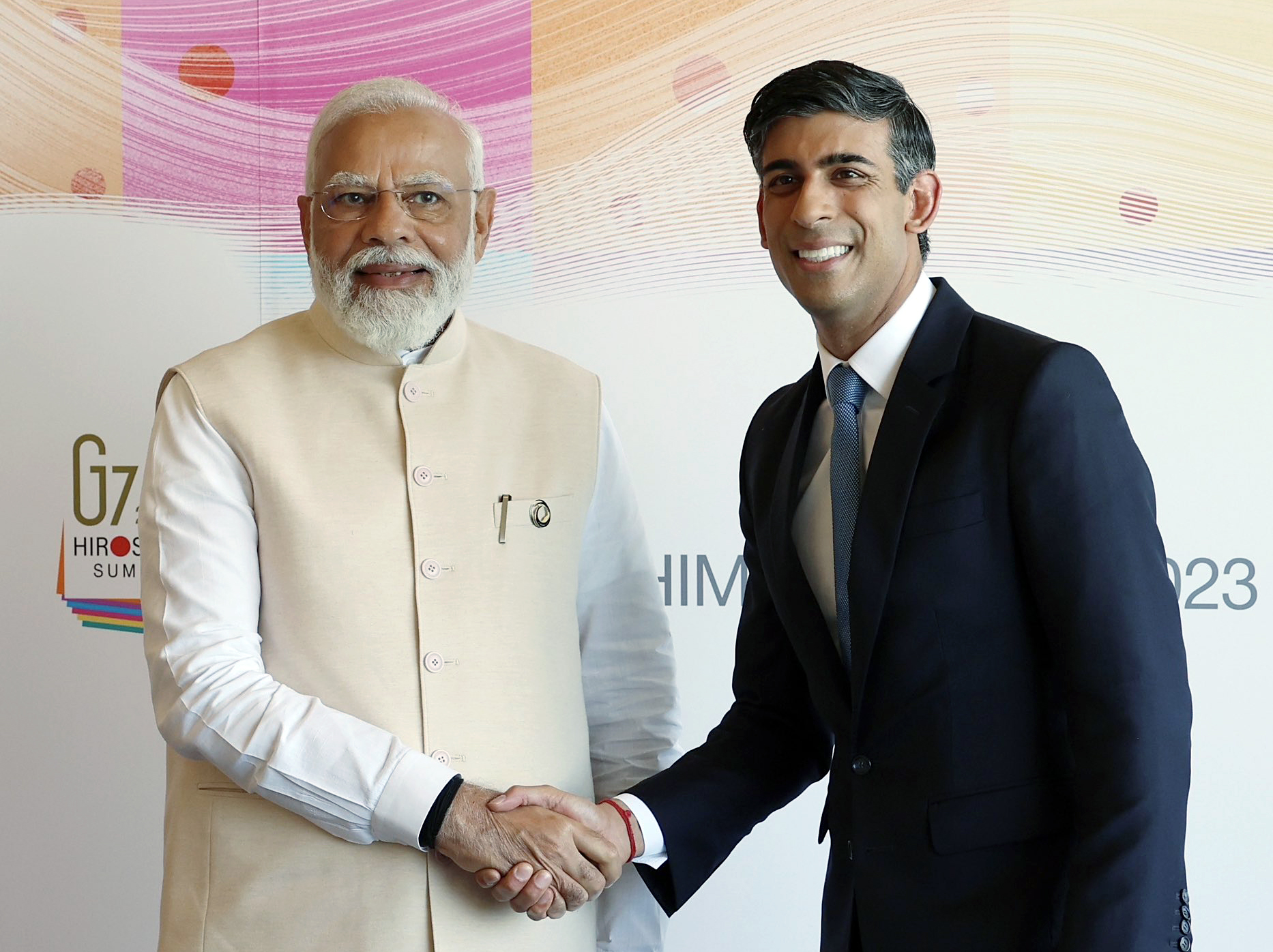

Last year witnessed an incident wherein pro-Khalistan separatists, advocating for an autonomous Sikh state in Punjab, vandalised the Indian High Commission in London and assaulted a member of the staff. The measured response from the UK government was adjudged insufficient by India, fuelling broader disillusionment with the UK’s approach. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s displeasure is underscored not merely by these events, but by a broader pattern of insensitivity rooted in arrogance. It has not escaped notice that the UK now boasts of its first Hindu Prime Minister. Yet whilst leaders like Biden and Macron have personally engaged with Modi, bar the G7 Rishi Sunak’s interaction has been absent. And whilst the Prime Minister of Japan, France and Italy tweeted their congratulations for the moon landing Sunak was silent.

Meanwhile, mainstream British media is viewed by many as patronising, and in certain instances, even culpable—illustrated by the Indian court’s pursuit of legal action against the BBC.

Media coverage of tensions between Hindu and Muslim communities in Leicester last year, despite being rooted in local grievances, was portrayed by certain mainstream platforms as emblematic of Modi’s BJP fomenting communal discord on British streets. While rightful criticism of misconduct should always find a place, the consistent negative focus on India and Modi, coupled with seemingly dismissive actions from influential quarters, raises a question: What prompts this negative sentiment towards India across British society, spanning from parliamentarians to media outlets? Could this perhaps be attributed to a lingering colonial legacy, an inability to view India as a partner rather than a former subject?

Modi’s recent visit to the United States exemplifies the essence of partnership with India. The communication was one of mutual respect, America realising India’s significance economically, geopolitically, and as a valuable workforce.

Congressman McCormick articulated the essence of this association as crucial for the future, describing America and India as two great nations.

Britain needs to take a good look at itself and begin engaging meaningfully across government and state apparatus with India. The India-hosted G20 is the obvious next opportunity; Trade Secretary Kemi Badenoch is using the G20 to kick off the “Alive with opportunity” campaign, which they hope will help double trade with India by 2030. These are welcome initiatives, but government rhetoric needs to be consistent, and the personal touch is imperative. Even when it comes to businesses a personal business to business mediator will be what it takes to get businesses to meaningfully engage. Simply promoting British businesses won’t be enough when mutual respect and understanding is lacking.

An imperative beckons: To view India as an equal partner, disentangling it from the confines of colonial history. Shedding the cloak of arrogance is requisite, for while Britain condescends, India leads and other nations seize the opportunities that a post-Brexit era demands.

- Charlotte Littlewood is Head of the UK-India Desk for the International Centre for Sustainability.