He was the man who showed the saffron brigade its space under the sun.

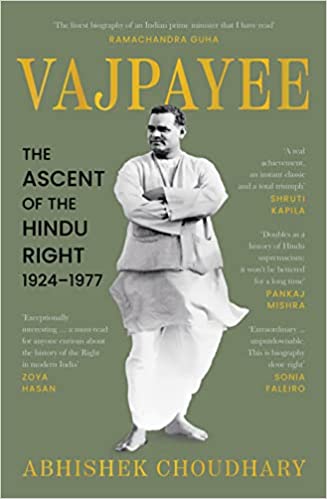

One of the most widely circulated videos of former Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee on YouTube revolves around his speech in Parliament on intolerance and how a portrait of Jawaharlal Nehru was removed from the corridors of the Ministry of External Affairs. It was done by someone in the hope Vajpayee would be pleased. But that was not the case. Vajpayee—despite his animosity against India’s first PM—did not like the idea of the missing portrait. The following day the portrait was back in its place. Speaking about it in Parliament, Vajpayee said politics is all about tolerance and that is something Indian politics is missing. In some ways, a new biography titled “Vajpayee: The Ascent of the Hindu Right 1924-1977” by Abhishek Choudhary highlights some of the intricate characters of the person who had a mind of his own and even questioned the effectiveness of the much-publicised Quit India movement of Mahatma Gandhi (read Congress). I am told this tome is the first of a two-part volume published by Picador.

So how would you analyse this one, which the publishers are claiming as the most definitive biography of the former PM and BJP supremo, a man who showed the saffron brigade its space under the sun with his magnanimity and ideas? I remember having met him once briefly when the Indian cricket team was headed for Pakistan in 2004. Vajpayee posed with the cricketers and wrote on a bat that was meant to be gifted to Gen Pervez Musharraf. Vajpayee scribbled, Match Nahin, Dil Bhi Jitiye (Not just matches, win hearts also). I am told Gen Musharraf, who died in Dubai on 5 February 2023, had treasured the bat for many years.

Choudhary says Vajpayee was a man of strong beliefs and would not mind changing his political stance even if he had been opposed to it at some stage of his life. For example, his relationships with both Nehru and Gandhi went through the highs and lows. And at the end, Vajpayee told his confidants that he learnt solid lessons of nation-building from both because both had interests of the nation uppermost on their minds. The book, thus, makes it clear that Vajpayee started his political career by openly opposing some of Gandhi’s strategies. And that Vajpayee was also critical of Nehru on many occasions. Yet, he admired both of them. Let me pick up some lines from an essay Vajpayee wrote way back in 1947 and reproduced in the book: “Whereas the second world war was a time to strengthen ourselves militarily, the opportunity was wasted on individual satyagraha which ended, as always, with sitting purposelessly in the jail.”

“World War I fuelled the Pan-Islamist ambitions of Indian Muslims. Around this time, Gandhiji, along with the Ali brothers, frequently invited the Afghans to invade India. But fortunately the Gandhi-Muslim conspiracy got noticed, and thus 30 years ago that disgusting attempt to convert India into Pakistan was thwarted,” wrote Vajpayee about Gandhi.

But then, see the change in Vajpayee when he says the following in 2002 while inaugurating a street named after Gandhi. Vajpayee makes it clear that Gandhi’s teachings continued to be relevant in the 21st century. “Throughout his life, he (Gandhi) preached and practised mutual tolerance and understanding among people belonging to all the religions of the world. In this, he echoed the age-old conviction of India’s civilization that truth is one, the wise only interpret it differently,” he said. Some of Vajpayee’s letters and essays were reproduced by pro-right publications and also by Panchajanya, the mouthpiece of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). In the Indian epic Mahabharata, Panchajanya is the conch shell used by Lord Krishna to herald the start of the battle between the Pandavas and Kauravas at Kurukshetra.

The book gets deep into the mind of Vajpayee and tries to highlight what he thought was right and what he thought was wrong. For example Gandhi’s fast-unto-death in January 1948 drew some severe criticism from Vajpayee, claims the author relying on his research from several right-wing publications and books. But eventually, claims the book, Vajpayee emerges as a solid politician and a mature parliamentarian who earned accolades from politicians cutting across party lines.

Vajpayee, however, managed to evade arrest when RSS was banned after Mahatma’s assassination in 1948. But he slowly emerged from the shadows and was seen as a democrat whose ethos was cemented in RSS ideology. It was an interesting dual personality of Vajpayee.

And then, look at the way Vajpayee described Nehru in the United Nations, saying in total admiration: “There was a flutter in the assembly and all delegates moving here and there rushed to their respective seats. Pandit Nehru was in his white Gandhi cap, Coca-Cola coloured sherwani, the invariable red rose, and churidar pyjamas.” The author makes it clear that Vajpayee was proud of Nehru, and proud of almost anything and everything Nehru did at the UN. “His confident manner of address, his clear and perfect accents, his well-formed turns of expression,” everything impressed Vajpayee.

The author writes brilliantly about Vajpayee’s visit to the UN and then, checking out museums and art galleries in New York, also the night clubs where he was accompanied by a young IFS officer, M.K. Rasgotra. It seemed modernism was seeping into the young politician who was opening up to the changes sweeping the world.

And then, almost in the same tone, the author says it was the same Vajpayee who felt Hindutva was the only genuine model of secularism and slowly, yet steadily, he adapted himself to the new world of the BJP. In short, he stamped the seal of Hindutva on India. It was a far, far cry of the person who was initially against the Ram Temple movement but the same man who encouraged Lal Krishna Advani to go on the rathyatra.

There were times when he was stubborn; he wanted the UP government to ban children of 16 years and below from watching films. It was almost like the Marxists banning English till Class IV in government schools in Bengal. Said an enraged Vajpayee: “Cinema is one of the reasons for the decline in the moral character of India’s youth; and since the government controls the cinema industry, it bears the responsibility entirely. For an annual income of merely 60-70 lakhs, no civilised nation would like to see its future citizens degraded.” Many felt Vajpayee did not like the Raj Kapoor starrer Barsaat, and even influenced some ministers to stop its screening six months after the movie’s release.

The author, whose brilliant research makes the book immensely readable, says Vajpayee was against any extreme form of religion. But at times he was weak and displayed his weakness when it came to members of his extended family and their business interests. There are many such examples in the media.

I cannot make out the reason for the book to hit the stands now, and then another one to hit the stands sometime later. There are multiple books on Vajpayee already in the market, right? Or is it that someone is trying to send some subtle messages to the current dispensation, making them aware that tolerance is the only way forward?