Much has been written this month about well-crafted novels and poetry collections, from the past year’s literary bounties, but there wasn’t nearly enough about the versatile form of the essay. Speaking of American publications, I liked the 2016 Best American Essays collection edited by Jonathan Franzen, as well as Cynthia Ozick’s Critics, Monsters, Fanatics and Other Literary Essays, both published by Houghton Miffin Harcourt. The former’s foreword is a delight—we learn here that when Elizabeth Peabody showed Ralph Waldo Emerson an essay written by her future brother-in-law Nathaniel Hawthorne, Emerson complained that the essay “had no inside”—and is followed by some diverse, enriching offerings including “The Lost Sister” by Joyce Carol Oates, “Pyre” by Amitava Kumar, and “A General Feeling of Disorder” by Oliver Sacks.

The collection of essays by Ozick, too, sets high standards for itself; and as good readers, we need to have done so for ourselves, explored threadbare the ideas, epistemes, and imaginations of our times. Lionel Trilling’s doomed-to-death moral life and Virginia Woolf’s self-inflicting modernisms, Orwell’s anomie and Eliot’s all-conquering “I”—the breadth of the essays astounds. What one finds here are debates rather than dogma, syncopation rather than certitudes. The legacies of Marcus and Franzen, for instance, with Franzen championing entertainment through conventional narratives, the pleasure of reading sans difficulty, and Marcus, the “enemy of audience-friendly writing,” sternly proposing experimental literature that disrupts syntax and sensibilities. Marcus versus Franzen, Woolf and Joyce, Naipaul and Henry James: in its deft positing of perspectives across past and present, we see Ozick’s craft. This is the writer as litterateur, historian, economist, cultural critic, philosopher, traveller.

One might wonder if Ozick’s excellent collection is also arduous, or if there are moments of pedestrian pause and intermittent joy. One such delightful moment for me was Ozick’s dismissal of a subset of critics who, not being fiction writers themselves, cannot fully appreciate writerly freedoms of play. These are the specialised academic theorists, with their bulky frameworks and political myopias, the dons and doctors “with advanced degrees worthy only of a parenthesis”. Ozick’s bristly position here stands in contrast to the generosity and soul of the rest of her writing. Her critique, common in an age of populist excess, albeit not always misplaced, made me chuckle—especially as she seems well aware of the pitfalls of such populism elsewhere. The book is brilliant. It is also the harbinger of happy news: the novel never dies, and whatever be the vicissitudes of eras bygone and unborn, we shall overcome.

Then there is the Pulitzer Prize winning poet Mary Oliver’s collection of essays called Upstream (New York: Penguin, 2016). Upstream is lush landscapes and lucid prose, filled with ras, and punctuated with flashes of startling insight, like starbursts in a night-sky. When she speaks of walking alone, upstream, in the midst of ripples and the company of violets; of bloodroot, fern, the wild music of the water thrush. Of mysticism, and manifestoes, of seeing in a butterfly the idea of transcendence. Or of trees: “One tree is like another tree, but not too much. More or less like people—a general outline, then the stunning individual strokes. Hullo Archibald Violet and Clarissa Bluebell. Hullo Lillian Willow and Noah, the oak tree I have kissed every first day of spring for the last thirty years. And in response, its thousands of leaves tremble.”

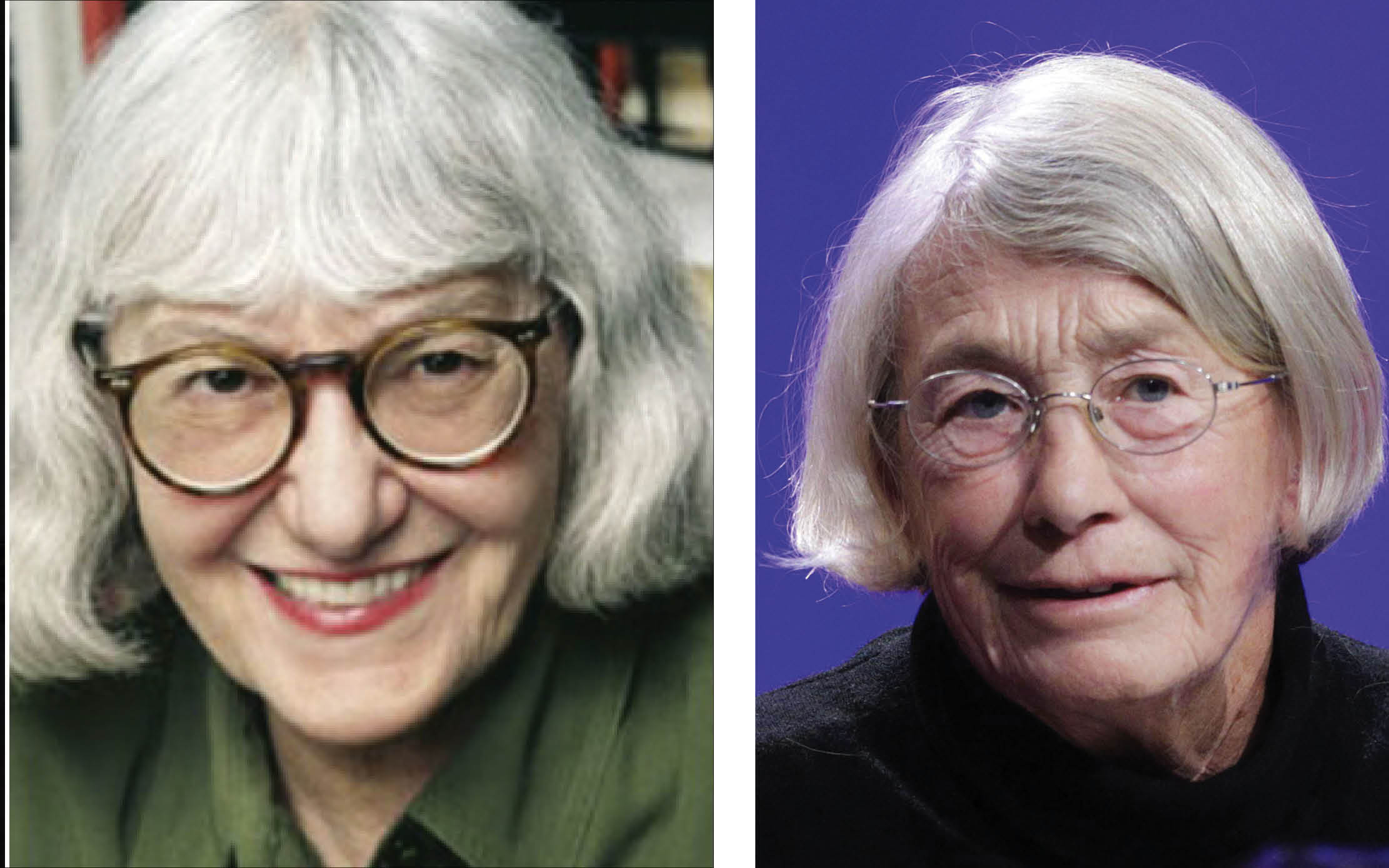

Oliver’s palette is all green, russet, and blue; we are told that in her forested, fairytale universe, there is no place at all for dusty industrial fumes, personal ambition, or injustice. Given the rather simplistic nature-industry binary in much writing that leaves the harder questions unanswered—our lives run on industrial goods, and paper for books comes from felled trees—Ozick’s collection holds up “isms” to more complex judgement, reminding us of the gaps between rhetoric and reality, and the tyrannies also sprung from egalitarian intent. I recommend Ozick in the morning and Oliver at night, once the day’s dust settles. For generous readers, they might pair up nicely. And while neither dwells much on gender, despite their positioning within Western literary traditions that for long associated men with intellect and women with bodies, one notes with some satisfaction that these brilliant essayists both happen to be women.