New Delhi: Last year, two videos that went viral across India involved two women athletes. Swapna Barman, heptathlete, and Hima Das, a runner. Barman’s mother broke into a paroxysm of sobbing watching her daughter win the Heptathlon in the 2017 Asian Athletics Championships. And Das wept silently on the victory podium after winning the IAAF U20 Championships. Tears rolled down her cheeks as loudspeakers played the Indian anthem. The videos were as powerful as Saurav Ganguly waving his shirt at the Lords and M.S. Dhoni lifting the World Cup. Sports cognoscenti called it the rise of women power in Indian sports, more than three decades after Southern runner P.T. Usha burnt the tartar track at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, missing the 400m hurdles bronze by a fraction of a second. The following year at the Jakarta Asian Games, she picked up five golds and one bronze, prompting an enraged Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi to comment: “Why send a whole contingent? We should have just sent Usha.” India instantly agreed.

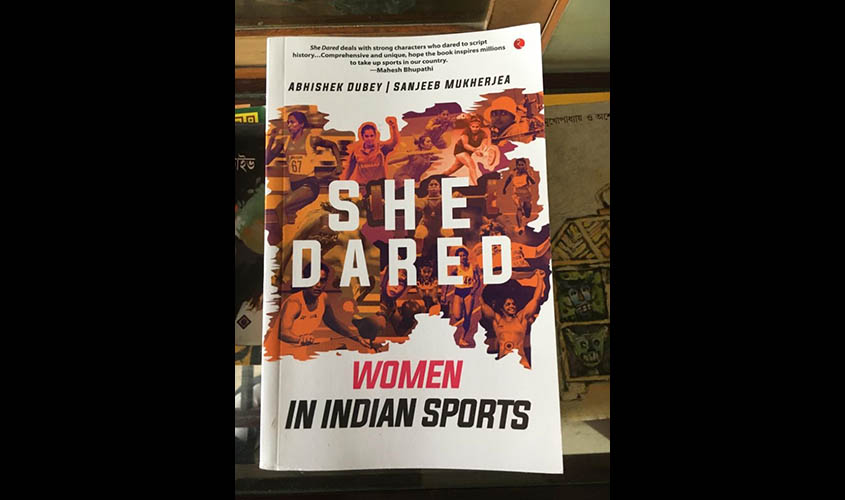

Indian sportswomen have always struggled on the field, and struggled double outside it to remain in the reckoning, their efforts ranging from seeking boots to endorsements. Once, a top Indian female shuttler posed with a cricket bat to tell advertisers that India is not just about cricket but other sports too. She Dared: Women in Indian Sports by seasoned sports journalists Abhishek Dubey and Sanjeeb Mukherjea takes a serious look at rising women power in Indian sports and exhorts cricket-crazy Indians to light candles whenever these women win medals. The writers, I am sure, know it is a tough call in India where cricket continues to rule the day, and night (we have now the pink ball night test). But the book has several accounts of such athletes who rose to fame despite having little or no support from organisers. It’s a reality, everyone knows who the BCCI president is, no one knows who the president of Badminton Association of India is. Despite such drawbacks, women stars are emerging from all corners like Banzai soldiers.

But it is still tough for sportswomen in India. Consider the case of top gymnast Deepa Karmakar. Many confused her state Tripura with Bangladesh and even felt she was a part of a circus. The book narrates the life and times of archer Deepika Kumari from Jharkhand whose father drove an auto-rickshaw and her first stipend was a pittance of Rs 500. I am sure even the junior-most cricketer in India will laugh at that allowance. Kumari told the authors how people equate her as a sportsperson from the land of M.S. Dhoni. Karmakar said how she defied odds to get into the difficult Produnova vault in gymnastics, considered among the world’s top ten toughest sports. Many told Karmakar it was tough and she said she would take the risk. Some in Ranchi told Kumari to act in films, she almost said yes but then backed out to be an archer. Kumari, the long-ranger, is now called the Rani of Jharkhand. She Dared narrates the story of boxer M.C. Mary Kom, who lost her cash before a crucial bout in Bengaluru and lost her father to a bullet wound. How many Indians know it? Indian news channels and news magazines routinely do women-centric shows to raise cash but always call women from the corporate world. Wouldn’t it be great if the board of Reliance Industries or the board of Tata Sons would call Mary Kom and do coffee and conversations, maybe a bout of boxing? But then, it would not happen because women in sports in India spend more time struggling to keep both ends meet. And it is not just in India but it is happening across the world. Recently, I read in the New York Times how all 28 players on the US women’s football team filed a gender discrimination lawsuit against the US Soccer Federation; the daily called the move “an escalation in their increasingly public battle for utility”. I guess the same happens in India, as described in this beautifully crafted book, published by Rupa, which highlights how women play more than men yet receive less pay because very few care in India.

The book highlights how institutionalised gender discrimination often impacts the pay cheques of these sportswomen, their training and medical care, and more importantly, their coaching. I remember how, for generations, experts in the US claimed that distance running was damaging to women’s health and femininity and stopped women from enrolling for Boston Marathon—Kathrine Switzer entered as K.V. Switzer to hide her gender but was pushed when men realised she was a woman—and in India how the BCCI looked to the women’s team as a group of girls on dole. And how the All India Football Federation, until some years ago, did not even care for the women’s team.