It is not just the BJP but all parties show eagerness to discard conventions.

Much has been said and written for and against the Central Vista that is aimed at changing the face of Lutyens’ Delhi. Little has appeared about the philosophical, ideological, and political underpinnings that made such an endeavour possible in the first place. The government has been accused of disrespecting colonial traditions and conventions, and that may be correct. This, however, has not been the first instance of such disrespect; politicians of all parties have done it earlier.

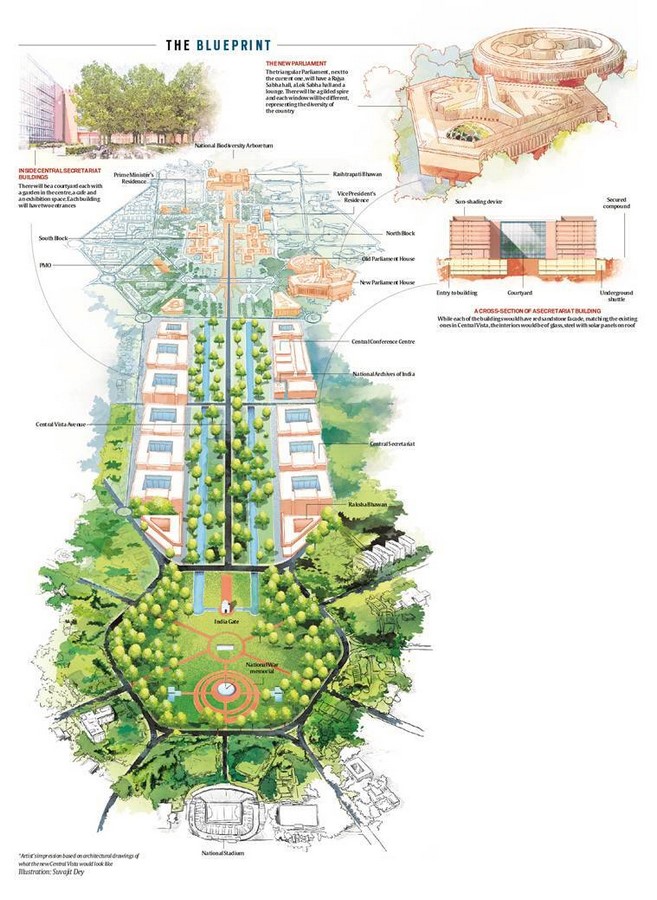

Let’s scrutinize the justification given for the Central Vista. In a recent article, Principal Economic Adviser Sanjeev Sanyal wrote, “When the British built New Delhi after 1911, they envisaged a different hierarchy—that is of a global colonial empire projecting power through an outsized Viceregal Palace (now Rashtrapati Bhawan) as well as North and South Blocks. The imagery is literally of an all-powerful Empire peering down on the subjects from Raisina Hill.

Anything colonial is fair game in Indian politics. Since British legacy is universally regarded as vile and iniquitous in our country, our leaders don’t have great regard with the traditions and conventions associated with it. Ditto with the physical structures built by our erstwhile colonial masters.

This attitude, however, is at odds with the fact of democracy in India being modelled on the Westminster pattern, which in many countries runs on the strength of precedents, traditions, and conventions. In the West, especially in Anglo-Saxon countries, traditions and conventions are taken very seriously—not just by politicians but also people at large. The US President, for instance, officially pardons a Thanksgiving turkey. This is part of an annual White House tradition that dates back to Abraham Lincoln.

Then there are British conventions which play a major role in UK politics. “A convention is an unwritten understanding about how something in Parliament should be done which, although not legally enforceable, is almost universally observed,” the British Parliament’s website says.

The world changes, and so do traditions and conventions. So, the tradition of Thanksgiving turkey pardon was restarted by President George H.W. Bush, and has continued since unabated. But in Anglo-Saxon countries, their traditions and conventions are never taken cavalierly, as happens to some of them in India.

Disrespect for democratic traditions and conventions is not an abstract subject; it has real consequences. Let’s consider a major upshot.

When in the 1989 general election no party got a majority, president R. Venkataraman first invited Congress party leader Rajiv Gandhi as the Congress, with 194 seats, was the single largest party in the House. After he declined to form government, the President invited V.P. Singh.

President Venkataraman stuck to the so-called “arithmetic test/objective test.” On 15 May 1996, President S.D. Sharma went by the precedent set by his predecessor and appointed Atal Bihari Vajpayee as Prime Minister. It was a decent test because arithmetic and objective facts can scarcely be debated. It was also in consonance with the famous Bommai judgement of the Supreme Court. The apex court had ruled that only a floor test could determine whether or not a government enjoyed the support of the legislature, be it the Lok Sabha or a Vidhan Sabha.

The next President, K.R. Narayanan, however, changed the convention after the 1998 general election by asking Vajpayee to submit proof in the form of letters of support to him. In other words, a precedent, set up by a President (Venkataraman), scrupulously followed by another (Sharma), was thrown away by the third President. The result is that whenever elections lead to a hung Parliament or Assembly, which is quite often, confusion prevails. Parties interpret various precedents and the Bommai verdict according to their convenience.

Leaders of all parties seem to be either apathetic if not hostile towards precedents, traditions, and conventions. It is not just the BJP but all parties show eagerness to discard conventions. In April 2010, the then environment minister Jairam Ramesh termed the practice of wearing the traditional robe at convocation ceremonies of universities as a “barbaric colonial” relic. In recent years, Lok Sabha Speaker Om Birla replaced “the ayes have won” with “haan paksh ki jeet huyi”.

The Central Vista project derives its philosophical and ideological roots from its refusal to abide by traditions and conventions. One reason for such disrespect may be that traditions and conventions are a kind of constraint on them—something not many Indian politicians are comfortable with.

There is another reason that is mostly referred to by the saffron establishment: its discomfort with the last several centuries of Indian history. First there were Muslim rulers from Afghanistan, Iran and elsewhere playing havoc with the Vedic ethos, demography, culture, and temples; then there were the British seeking to create Macaulayan men and women content to remain slaves. Before 1200 AD, history has been deliberately and repeatedly intertwined by those in thrall to Macaulay (especially from the Left) with folklore and mythology, as though Hindus have rarely been historians or ever had heroes among their number. They forget Edmund Burke (1729-97), the father of conservatism, who wrote, “Society is a partnership of the dead, the living and the unborn.” In other words, in the conservative scheme of things the past, the present, and the future form a continuum. Many nationalists, however, don’t agree with such views. And so, the government wants to build the nation anew; and it wants that beginning to be less connected with the past. The Central Vista is intended to symbolize that new India.

Ravi Shanker Kapoor is a freelance journalist.