India ramping up its border infrastructure has caused uneasiness on the other side of the LAC.

“From the very beginning of the war, the firepower of the Indian army was extremely fierce. After two hours of fierce fighting, though the Chinese army occupied Galwan Valley, but the price it paid was too heavy. 874 Chinese soldiers fell on the icy snow of this river valley. It was not until the beginning of the1980s that the bodies of more than 800 soldiers were brought back from the frozen snow.” Thus wrote Sun Xiao, a People’s Liberation Army (PLA) officer in the Snow of the Himalayas: Sino-Indian War Records (Chinese edition 1991). Sun says that in 1982, when he visited Xinjiang, he was witness to the remains of these soldiers being transported from Ngari (Ali) in Tibet to Urumqi in Xinjiang. The Indian official version of the 1962 conflict, the History of the Conflict with China, 1962 (unpublished report), edited by S.N. Prasad (1992) says that “the Chinese attack on the [Galwan] post started with heavy artillery and mortar bombardment on 20th October at 0530 hours…After an hour of shelling the Chinese attacked the forward sections with nearly a battalion strength. The men who had moved to open trenches fought a bitter last ditch battle…it was only towards the evening that the Chinese finally succeeded in overrunning the post. In all, the Chinese launched three attacks. The casualties suffered by the defenders, 36 killed out of a total 68 all ranks, shows how bitter the fighting was”! The Chinese official version of the conflict, entitled History of China’s Counter Attack in Self-defense Along the Sino-Indian Borders (Chinese edition 1994), gives the total Chinese casualties in the entire western sector as 97 all ranks!

The same Galwan valley is in the news again as we hear of intrusions by the PLA beyond their claim line of 1960. If so, this is a new development and bad news for both India and China. Alastair Lamb, who has done considerable research on the India-China border, remarked in 1964 that “the extent of Chinese claims seems to increase slightly from time to time” in the Western Sector. Rightly so, as there are three Chinese claim lines in the Western Sector. One is the claim line of 1956, which intersects the Aksai Chin almost into two; the second is the line separating the Indian and Chinese forces on 7 November 1959, and the third, the line reached by the Chinese after the 1962 conflict. China did go back 20 kilometers behind the Line of Actual Control in the Eastern Sector, i.e. Arunachal Pradesh, but not in the Western Sector, where they reinforced their 1960 claim line. The Chinese message was clear, accept our claims in the Western Sector, we will accept the McMahon Line. It was this stand that China hinted at in various semantics albeit she had gone back from the 1956 claim line and had demanded more territories beyond the 1956 line, in 1960. Neville Maxwell, while criticizing India for its “forward policy”, remained tight-lipped about China establishing forward posts beyond their 1956 claim line. Thus, he accepted different claim lines put forth by China in the Western Sector as their legitimate right. Therefore, to say that the entire Aksai Chin was under Chinese jurisdiction is not correct, nevertheless, the status quo has been drastically changed by China. If the reality of China’s different claim lines, together with the Shyam Saran report of 2013 and Professor P.A. Stobdan’s study is to be believed, Ladakh has been shrinking in size.

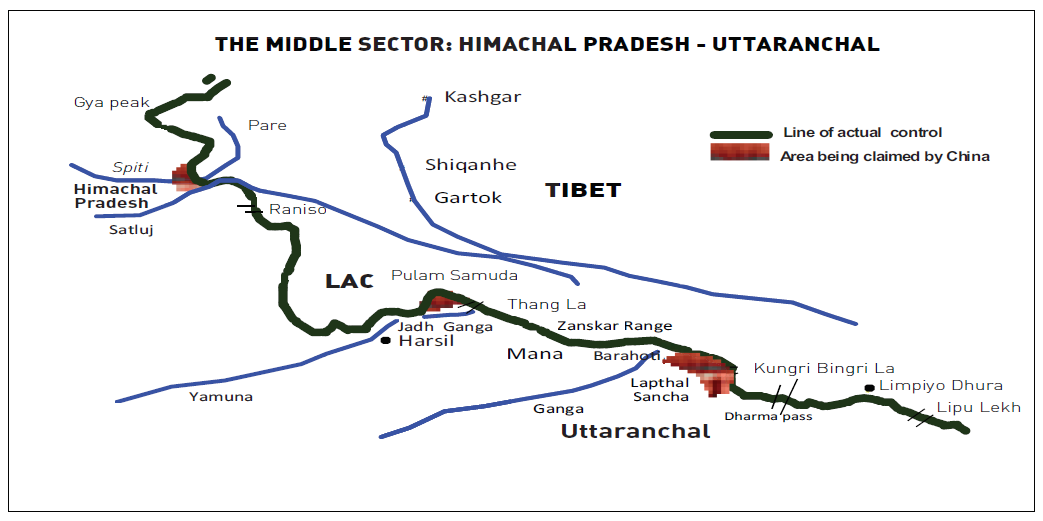

This has been demonstrated by ever increasing transgressions, mostly in the Western Sector by the PLA—the Galwan valley; the Srijap range where India’s claim line extends to Finger 8 but doesn’t control the areas beyond Finger 4; and Naku La in Sikkim. India must be watchful for similar flashpoints in the Middle Sector, in areas such as Nilang-Jadang, Bara Hoti, Sangchamalla and Lapthal, Shipki La and Spiti as these are also claimed by China. Interestingly, having reinforced its 1960 claim line in the Western Sector, China is playing victim and accusing India of “provoking the incident” in Galwan valley “intentionally” and “trying to change the status quo unilaterally”; the version since 18 May has appeared in various print and social media outlets in China. Social media has been carrying reports of the 1962 flash points in this area and singing praises of the PLA’s valour. Wang Dehua, a veteran of India-China relations in an article in sohu.com on 19 May 2020 has even warned Prime Minister Narendra Modi that “Boundless is the sea of misery, yet a man who will repent can reach the shore nearby.” Why is China behaving like this?

First of all, border is not the biggest agenda for China at this point in time. China believes that it has not reached the stage where a resolution is a must, therefore, for it, peace and stability in the neighbourhood is the top priority, along with transforming China into a “moderately developed power” by 2049 when it will realise the second centenary, i.e., a century of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, and perhaps the unification of China too. Therefore, “maintenance of peace and tranquility” and “managing” rather than solving the problem will be its top priority.

Secondly, it is also not a big agenda for China, as it has easy access to the Line of Actual Control (LAC) owing to the state of the art infrastructure it has created. China knows that the CBMs that both sides have created will not be enough to resolve the problem, hence no stone should be left unturned as far as infrastructure development in Tibet and Xinjiang is concerned. For example, the “Thirteenth Five-Year Plan” (2016-2020) allocates 200 billion RMB ($20.5 billion) for infrastructure development in Tibet. Today 99% of the villages are connected to highways, as the network in the region has increased from 65,000 kilometers to 90,000 kilometers. These roads are further connected with major railway lines inside Tibet and Xinjiang.

Thirdly, since India is also ramping up its border infrastructure “rapidly”, this has caused uneasiness to the other side of the LAC. Although the 255-kilometres-long Darbuk-Shayok-Daulat Beg Oldie (DS-DBO) road took us 19 years to complete (not to talk about the scandals associated with these projects), nonetheless, it will make accessible many areas of the LAC for patrolling and will keep an eye on Chinese movements in Aksai Chin. There are 60 more such projects that are part of the 3,300-kilometre road network along the border, the work of which was supposed to be completed in 2019 but according to the Border Roads Organisation (BRO) officials, only 75% of the work has been completed. Surveys for border rail projects such as Bilaspur-Manali-Leh, Misamari-Tenga-Tawang, North Lakhimpur-Bame-Silapathar, and Pasighat-Teju-Parsuram Kund-Rupai are on and are supposed to be completed by 2025. It is perhaps this new “development” which has been a cause for concern for China. Therefore, it has been making forays into new areas simply for “holding the line” as they perceive it. India too perhaps will “hold the line” if more areas are accessible once the infrastructure is laid. This, however, will give rise to Galwan and Doklam like confrontations, which could lead to a larger conflict. I think this is also out of this thinking that China is contemplating the demilitarization of the LAC. India too perhaps could think of such a proposal if she feels comfortable with the notion of equal and mutual security, for the cost of maintaining “peace and tranquility” is becoming higher for both India and China.

Fourthly, many scholars and analysts in both countries have related the Galwan and Naku La standoffs with Covid-19 situation in India, and China taking advantage of that, which I believe is not quite logical. More than that I believe it is India cozying up to the US as far as our security interests are concerned; it has something to do with India’s close coordination with the Quad and Indo-Pacific strategy. India’s support for Covid-19 probe can also be seen in this light. Some Chinese scholars believe that India has been fishing in troubled waters as Sino-US relations have nosedived. Professor Wang Dehua even warns India that “recently, due to the rapid deterioration of Sino-US relations, New Delhi has forgotten its history and has started to bloat a bit”, which I believe is uncalled for.

Finally, rather than flaring up jingoism, both India and China must go back to the “consensus” reached in Wuhan and later in Mahabalipuram, reactivate all available confidence building mechanismsand restore the status quo ante. They must quickly dis-engage, for both cannot possibly push back their economies further, at a time when both are reeling under negative growth trajectories in the backdrop of Covid-19. This is the 70th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between India and China; both have planned 70 events to celebrate the year, unfortunately, we have started the anniversary with a very negative note.

B.R. Deepak is Professor, Center of Chinese and Southeast Asian Studies.