Roy’s book fails to grasp the complexities of the two gigantic characters. It leads to the unravelling of the superstructure of ideas which she creates in the beginning.

It’s truly an Orwellian world we live in. Here Mohammed Ali Jinnah is defended. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar is abhorred. And Babasaheb Ambedkar is worshipped. The three political leaders believed in the two-nation theory. Yet, they get different treatment despite holding a similar view on Islam and the idea of Pakistan.

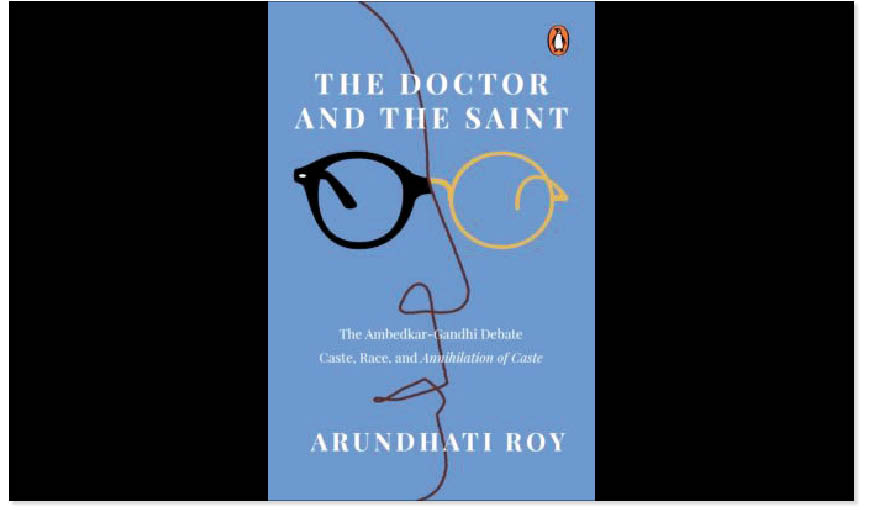

One may say Ambedkar is fortunate enough to escape the “secular” heat, but he is a victim in his own right. He has been selectively quoted and portrayed. In her latest book, The Doctor and the Saint, Arundhati Roy writes that “history has been unkind” to Ambedkar. “It has made him India’s Leader of the Untouchables, the King of the Ghetto. It has hidden away his writings. It has stripped away the radical intellect and the searing insolence,” she writes. Roy, in this book, unfortunately, can be accused of the same crime—of selectively quoting Ambedkar.

Yes, Babasaheb often reiterated that he was born a Hindu but he would never die as one. Yes, he called Hinduism “a veritable chamber of horrors”, a fact which Roy almost gleefully mentions in the book. Also, he believed that no real reformation was possible in Hinduism, given its obsession with the “degrading and discriminatory” caste system. “There cannot be a more degrading system of social organisation than the caste system. It is the system that deafens, paralyses and cripples people from helpful activity,” Ambedkar said.

The fact is Ambedkar didn’t die as a Hindu, as he had prophesised himself. But when it came to finding a new religion, for himself, he chose Buddhism—a religion deeply rooted in Indic ethos. For all his anger and rage against Hinduism, a religion that gave him and his fellow beings in the lower castes innumerable instances of grief, discrimination and suffering, he didn’t blind himself to the realities of the Semitic religions. “Muslims in India are an exclusive group, and they have a consciousness of kind possessed by a longing to belong to their own group and not to any non-Muslim group. Thus, the controversy must end and the Muslim claim that they are a nation must be accepted without quarrel,” wrote Ambedkar in support of the idea of Pakistan. But he didn’t stop there and, in fact, called for the transfer of minority population between India and Pakistan, citing the precedent of Turkey, Greece and Bulgaria.

This side of Ambedkar has the potential to turn him into an “untouchable” among India’s liberals. So, it’s deliberately kept under the wraps, and the focus, instead, is put on his caste-related works and words. Paradoxically, Savarkar is condemned for a similar stand on Islam and the idea of Pakistan. He is reduced to being the sum total of the two-nation theory, and in the process his other contributions, some of them being ahead of time, are pushed under the carpet. Why no such generosity for Savarkar? Was it because of his Hindutva connection?

As for Gandhi, Roy introduces him beautifully in the beginning of the book. She writes how he has “become all things to all people: Obama loves him and so does the Occupy movement. Anarchists love him and so does the Establishment. Narendra Modi loves him and so does Rahul Gandhi. The poor love him and so do the rich.” Maybe this was because Gandhi, to use V.S. Naipaul’s terminology, was a “bits-and-pieces man”, who adopted things from sources as different as his mother’s love for fasting and Leo Tolstoy’s religious belief to John Ruskin’s idea of labour, South Africa’s jail code. Here was the Mahatma who, to use Sri Aurobindo’s words, was “a European…in an Indian body”.

But Roy, after explaining how Gandhi “has become all things to all people”, does what she is often accused

Gandhi was a revolutionary par excellence. In an era when the caste system was rigorously entrenched, he gave a call for its reform. He sincerely worked for the entry of lower castes in temples, and it was his influence and hard work that made some perceptible changes possible. Ghanshyam Das Birla, one of the leading industrialists of his time and an avid Gandhi supporter, once said, “He was more modern than I. But he made a conscious decision to go back to the Middle Ages.” Gandhi went to the Middle Ages because he wanted to reach out to the masses stuck there for centuries. He wanted to win them over, take them along. His approach to reach out to Dalits and unntouchables might be different from that of Ambedkar, but his effort was genuine.

Roy’s book, in that way, fails to grasp the complexities of the two gigantic characters. It leads to the unravelling of the superstructure of ideas which she creates in the beginning of the book. Her black-and-white approach fails not just the Doctor and the Saint, but also the readers who expected a better book from the Booker Prize winner. Alas, the Goddess of Small Things has over the years become the Goddess of Utter Generalisations.