The orders were to ‘shoot at sight’, using machine guns, to break the ranks of the Krantikaris when they converged on Ballia. Not only did Jagdishwar Nigam disregard these orders, he went a step beyond and ordered the police to deposit their weapons.The orders were to ‘shoot at sight’, using machine guns, to break the ranks of the Krantikaris when they converged on Ballia. Not only did Jagdishwar Nigam disregard these orders, he went a step beyond and ordered the police to deposit their weapons.

We are living in an epochal time in India’s history. As a young nation, freed from the shackles of imperial rule just 75 years ago, India is today marching ahead to regain its rightful place in the comity of nations. As the nation celebrates 75 years of Independence in the ongoing “Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav”, attention invariably goes back to the heady days of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries which saw India fight for her Independence. This battle against colonial rule, spread over two centuries, encompassed people from all walks of life, many of whom remain unsung and forgotten. The contribution of many of these forgotten heroes of yesteryears is now being recognised and recorded, their individual and collective roles having contributed greatly to India eventually getting her Independence.

Not much is known about the role played by the Indian Civil Service in the struggle for Independence. The Indian Civil Service (ICS), officially known as the Imperial Civil Service, was the higher civil service of the British Empire in India during British rule in the period between 1858 and 1947. When India became independent, there were just under a thousand ICS officers, over half of whom were European. The Indian component was about 400 officers. For the most part, the Indian ICS officers followed British policy diligently and abstained from the freedom struggle. But during the Quit India Movement launched in 1942, also known as the August Kranti Movement, there was a notable exception.

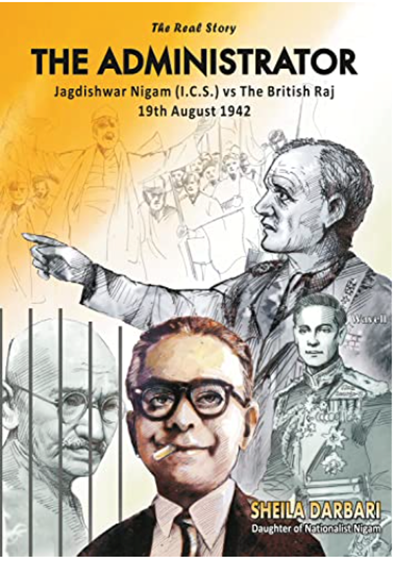

This book recounts the story of Jagdishwar Nigam, who was the District Magistrate and Collector of Ballia in 1942. During the Quit India movement, he refused to obey the orders of his superiors to quell the revolt in his district. The orders were to “shoot at sight”, using machine guns, to break the ranks of the Krantikaris when they converged on Ballia. Not only did Jagdishwar Nigam disregard these orders, he went a step beyond and ordered the police to deposit their weapons. He then had Chittu Pande, an independence activist and revolutionary released from jail and thereafter, the Indian flag was hoisted in the town hall, after taking down the Union Jack. The flag flew majestically for 14 days, till the British forces ultimately retook the district. Chittu Pande was a famous revolutionary of that time. Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose described him as the Tiger of Ballia. He headed the nationalist government, which was declared on 19 August, albeit for a few days only till the British suppressed the movement. Jagdishwar Nigam was subsequently tried by the British and was dismissed from service. He fought his own legal battle and was reinstated in the ICS shortly before India got her Independence. Post-Independence, he served as the Revenue Secretary in the UP government.

The book also provides an interesting anecdotal account of life in the British Raj and functioning of India’s steel frame. The author, Sheila Darbari, is the daughter of Jagdishwar Nigam, and as a young girl, she had occasion to see, first hand, the events as they unfolded. She also describes a private meeting which her father had with Mahatma Gandhi, three years before Gandhi launched the Quit India Movement. Gandhi was gracious and made the young girl sit with him, while he carried on the discussion with her father. This came to be a very cherished moment in the author’s life. An interesting facet of the book is that the author got down to writing it, when she was 90 years old, and completed the book, just before she passed away on 18 July 2020, leaving the publication of the manuscript to her daughters.

The book touches on many aspects of British rule, especially on their constant endeavour to create a wedge between Indians, dividing them on the basis of religion and caste. That was the basis of their rule, as a united India would have brought their rule to an end many decades earlier. The author posits an interesting reason for the partition, making a link with the British mandate for Palestine. As a large chunk of Muslim territory had been given for the settlement of Jews in Palestine, the British, to retain the goodwill of the Muslim world, gave a huge chunk of land to Indian Muslims in the form of Pakistan, as compensation. There were, of course other British motives to partition India, based on their larger strategic interests, which was why Jinnah was actively encouraged to demand a separate homeland for India’s Muslims.

There is also a telling comment on the antics of British officers. One such officer would tell his Indian subordinates to wait as he had a set of abuses for them. Then from his notebook, he would rant out a few choice abuses, merely for his amusement, before dismissing them. The poor subordinates would then depart, bowing down and thanking him profusely. In a sense, this pattern of obsequious behaviour can still be seen in India. Too many Indian government officers cringe before their bosses exhibiting a great deal of sycophancy in their behaviour. This hangover of the Raj too needs to go.

The book makes for interesting reading, and gives a varied glimpse of India in the first half of the twentieth century. The narrative at times appears disjointed, the flow not being even and sequential. It could have done with a good copy editor and better proof-reading. The book is interspersed with a large number of photographs, but it would have been better to have had just a few. Overall, the book adds value to the landscape of the freedom struggle, especially on the role played by Jagdishwar Nigam. We require more civil servants in our higher bureaucracy of that calibre.

Maj Gen Dhruv Katoch is an Army veteran. He is presently Director, India Foundation.