The article of faith for religious and liberal fanatics has fanned Muslim extremism, victimhood and alienation in the garb of providing special status to the state.

New Delhi: In 2019, Karan Singh completes 70 years in public life, having been appointed Regent of Jammu & Kashmir by his father, Hari Singh, in 1949. The year has also seen the historic revocation of Article 370, an article of faith for both religious and liberal fanatics which, in the garb of providing special status to the state, has fanned Muslim extremism, victimhood and alienation. Interestingly, with the Narendra Modi government calling the bluff on the Constitutional sacredness of Kashmir’s special status, the former Regent and Sadr-e-Riyasat of the state too makes an about turn vis-à-vis his long-held stand on Kashmir and relations with the Indian Union.

Singh, much to the surprise of many within and outside the Congress, said early this month that he did not agree with the “blanket condemnation” of the Modi government’s twin moves of removing special privileges given to the state and its bifurcation into two Union Territories. “I personally do not agree with a blanket condemnation of these developments. There are several positive points,” Singh observed. “Ladakh’s emergence as UT (Union Territory) is to be welcomed… The gender discrimination in Article 35A needed to be addressed as also the long-awaited enfranchisement of West Pakistan refugees and reservation for Scheduled Tribes will be welcomed,” he added. Singh also welcomed the possibility of fresh delimitation after the bifurcation of the state into Union Territories, saying the move would “ensure fair division of political power”.

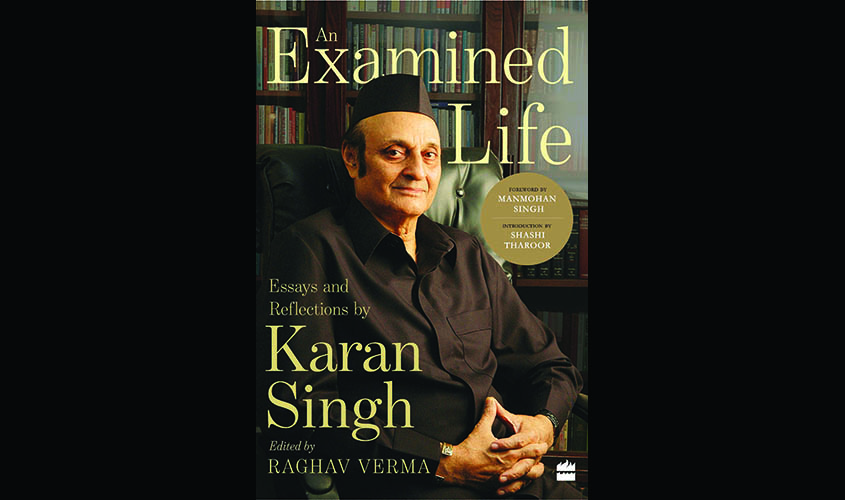

The statement seems to challenge the resolution of the Congress Working Committee, which “deplores the unilateral, brazen and totally undemocratic manner in which Article 370 of the Constitution was abrogated and the State of Jammu and Kashmir was dismembered by misinterpreting the provisions of the Constitution”. But what’s even more interesting is that the senior Congress leader has not just moved away from the party line but also contradicted his own stand on the matter, elaborated with much conviction and eloquence in his latest book, An Examined Life (HarperCollins, Rs 799), released in May this year.

“There is huge ignorance in our country about this (Article 370). They consider Jammu & Kashmir to be like any other state. The Instrument of Accession that my father signed was exactly the same as the ones all the other rulers signed, on that there is no question. But what happened after that was that all the other rulers, thanks to Sardar Patel and V.P. Menon, signed merger agreements, whereby they integrated their territories with India. But in J&K there was no such agreement. There was a war still going on and half of the state had already fallen under Pakistan’s control. So, our relationship with the rest of India was governed by the Instrument of Accession but, more importantly, by Article 370, granting a special autonomous status to Jammu & Kashmir,” Singh observes in the book.

Interestingly, he doesn’t stop there and goes on to emphasise that the “accession is complete but the state has not merged” with the Indian Union. “There is a lot of confusion when people of the Valley talk of autonomy,” he writes. “Autonomy is not independence. Autonomy is living with the fact that we have not merged.” The last Sadr-e-Riyasat of Kashmir also advises the “right-wing” to “be large-hearted” and that “it (J&K) would always be special because it is borne out of a special historical event and subsequent political developments”. Reminding of Scotland and Ireland’s ties with Britain and Hong Kong’s special relationship with China, he adds, “We should feel lucky that Jammu & Kashmir, a Muslim-majority state, became a part of India despite the religion-led Partition. Cherish that; relish that; honour that.”

The book, however, vindicates the division of Jammu & Kashmir into two Union Territories when it says that there is no such state as Kashmir. “It is Jammu & Kashmir, the state for which my father signed the Instrument of Accession and which my ancestors built. We conquered Ladakh, we conquered Gilgit-Baltistan. It was a Dogra empire. This needs to be understood historically. Jammu-Kashmir was never an integrated state. We kept these regions together for a century.”

So, when Union Home Minister Amit Shah moved Parliament to scrap Article 370 and divide the state into two, it, in a way, validated Singh’s assessment: That the Nehruvian construct of Kashmir was nothing but a mirage; that Kashmir wasn’t just about the Valley, that for every individual chanting azaadi slogans and pelting stones at security personnel, there were as many willing to stand up for the Tricolour and the National Anthem; that the move liberated Ladakh from being a colony of the state and gave wings to their long-held democratic aspirations.

Does it mean that An Examined Life is an obsolete and outdated book, especially in the wake of the author’s almost U-turn on Article 370, questioning the supposed sacredness of Jammu & Kashmir’s special status? No. The book is much more than just that. From his essays on the history and politics of the state to his takes on metaphysics, spirituality and religion—it is a collection of writings about the seven decades he has spent in public. The book also contains select poems and excerpts from his travelogues and novel set in Kashmir.

Amid all this, the author’s personal self too comes alive. Thus, we know how much Singh adored Jawaharlal Nehru, Dr S. Radhakrishnan, Sri Aurobindo and Swami Vivekananda. “I have two spiritual gurus (Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo) whom I did not meet. I also had two living gurus in Jawaharlal Nehru for politics and Dr Radhakrishnan for philosophy.” But he owed his life to Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. “Had it not been for him, I would have spent my entire life on a wheelchair,” he says as he recalls how Patel insisted that his father sent the unwell Karan to America for treatment immediately.

But what takes the cake is the author’s correspondence with Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter, Indira Gandhi. While his letters with Nehru casts light on the political turmoil in Kashmir post-accession, his interactions with Mrs Gandhi look at the dark and uneasy phase of Indian politics, in and around the 1975 Emergency.

Even in its failure to grasp the profanity of the so-called sacredness of Kashmir’s special status, the book is a recommended reading. For, it not just exposes the fallacy of the great Nehruvian order, but also highlights the audacity of the Modi-Shah combination to dare to swim against the tide of the liberal consensus.