‘No inquiry was ever done to fix responsibility on the CBI officers who allowed Shankaran to escape’.

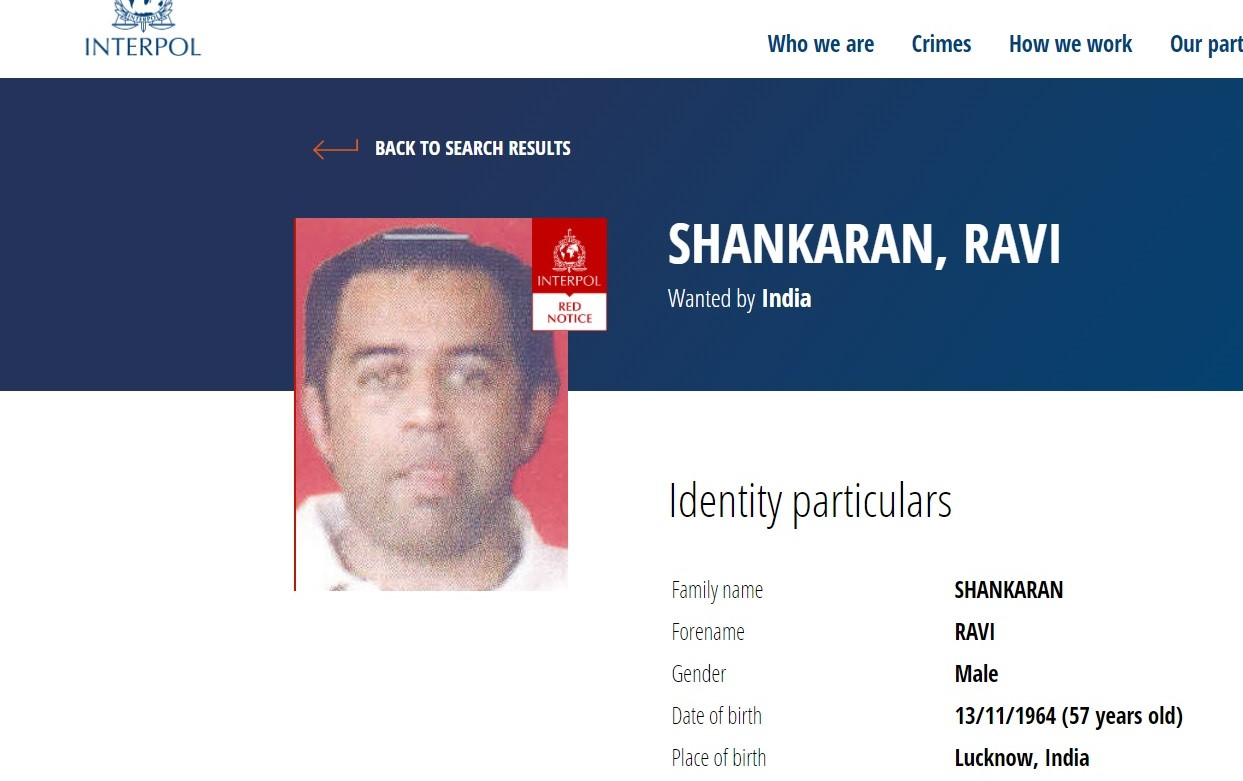

New Delhi: Former Indian naval officer, Lieutenant (Retired) Ravi Shankaran, who was the brain behind the leaking of classified information related to Indian defence assets—which came to be known as “Naval war room leak” case—is now well settled in London.

Sources told The Sunday Guardian that the 57-year-old Shankaran, whose father Raju Shankaran was a colonel in the Indian Army, is a regular customer at the iconic five-star Dorchester hotel, London, where he hangs out with his friends almost every weekend, as he did as recently as earlier this month.

The Sunday Guardian has also learnt that Shankaran, against whom a Red Corner Interpol notice is still pending on a request forwarded by India, has been staying in one of the many picturesque residential buildings near Chelsea Harbour, Fulham, Imperial Wharf, West London.

Shankaran, who is addressed as “Shanx”, allegedly had earned at least $200 million for the about 7,000 pages of sensitive documents that he managed to smuggle out from multiple defence establishments and sell it to arms companies and dealers.

After serving in the Navy for eight years, Shankaran retired in 1994 to set up a company with another recently retired naval officer. The company became a front for facilitating arms deals between foreign companies and serving Indian military officers who were trapped, lured and compromised by using money, liquor and foreign service girls. This newspaper has accessed several pictures of such meetings.

When the news about the leak of the sensitive documents from the Navy and Air Force headquarters broke, Shankaran fled from India, after which the CBI registered a case against him in March 2006. After it emerged that he was hiding in London, an extradition request was sent to the UK in 2007, following which he was arrested by UK authorities in April 2010. After being released on bail, Shankaran challenged his extradition order that was approved by the then UK Home Secretary Theresa May.

On 1 April 2014, the Queen’s Bench Division (Administrative Court) of England and Wales disallowed his extradition on multiple grounds including the failure of the CBI to prove that Shankaran was involved in the case and the inordinate delay in commencing the trial in the case.

The judgment said that the CBI had failed to prove that documents were shared between the accused(s) that included Shankaran’s business partner Kulbushan Parashar and serving naval commander Vijender Rana, who at the time was posted at the Directorate of Naval Operations.

As per the CBI, eight classified word files were sent by Rana using his email to a person named Vic Branson, which was an email address being used by Shankaran. However, the CBI could not present substantial proof to substantiate this assertion. In order to prove this theory, the CBI had presented three different statements of P.S. Kushwaha, who worked for Shankaran’s company for more than a decade. These three statements were recorded on 3, 5 and 6 June 2006.

However, what derailed the CBI’s assertion and helped Shankaran’s case was that in the first statement, Kushwaha had stated that he was not aware of Shankaran using any email address by the name of Vic Branson. In the second statement, he stated that Shankaran used only two email addresses, none of which was in the name of Vic Branson. It was in the final statement that Kushwaha agreed with the CBI’s assertion that Shankaran was using an email address in the name of Vic Branson.

None of these statements were signed by Kushwaha or a magistrate, something which was also observed by the UK High Court. All these three statements, presented before the court, were taken under Section 161 of the CrPC (Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973), which defines “Examination of witnesses by police” and not under Section 164, which talks about “recording of confession before a magistrate”.

This was a small procedural necessity, which is known even to a police constable, but since it was not followed by the CBI, it ensured that the entire effort of the Government of India to extradite Shankaran, collapsed. No inquiry was ever done to fix responsibility on the CBI officers who allowed Shankaran to escape and flourish despite the change of government at the Centre.