Charu Majumdar’s death crushed the Naxalite movement and CPI(ML) was fragmented into various groups.

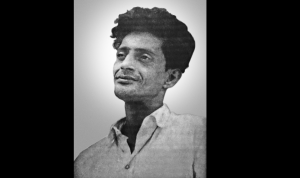

Charu Majumdar, who made Mao Zedong’s lines, “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun”, popular during the Naxalite movement, hoodwinked the cops in Calcutta (not Kolkata then) for long.

But he was eventually caught. So, let’s read the lines from this chapter, titled “The Early Morning Knock”, from Niyogi Books series on “Pioneers of Modern India”. This one is titled “Charu Majumdar, The Dreamer Rebel”.

Author Ashoke Mukhopadhyay captures the mood that night. There was a pounding on the door. “Open the door, quick, quick, open the door,” screamed constables of Calcutta Police. It was the wee hours of the morning. Arabinda, a comrade, wondered who could have come. The ceiling fan was at its full speed, yet it couldn’t help make the night’s heat and humidity unbearable. The person on the cot, under the mosquito net, was sleeping quietly. He was not well and did not eat anything in the last 24 hours. In fact, he had been suffering from tremendous breathing trouble.

The voice outside got louder; it could be heard through the ventilator above the door. The moment Arabinda opened the door, a few men in ordinary clothes barged into the room and made him immobile.

One from the gang howled: Who is under the net? He tore away the net and said: “Get up Charu Babu, your game is over.”

The frail man followed the instructions and quietly said: “Who are you?”

“We are the police and my name is Debi Roy,” he said with a smile. “You are…”

“Yes, I am Charu Majumdar.”

Arabinda was tormented by two questions. Who had disclosed the address, which was a highly guarded secret? Only one comrade at Deb Lane shelter, Dipak Biswas, knew of this house. Secondly, would the police kill Charu Babu, the way they had murdered Saroj Dutta? Wasn’t it the plot of Anik Dutta’s highly-acclaimed movie, Meghnad Bodh Rahashya? The betrayal of a fellow comrade to seek a passage to the UK. In return, he told the cops where a fiery Naxalite was hiding. The hideout was an unused, dilapidated zamindari close to Santiniketan. Those who watched the film had remarked the betrayal in the movie was a reflection of the life and times of Charu Majumdar. Someone had spilled the beans to the cops about Majumdar’s hideout.

The diminutive book, brilliantly researched and written, is full of anecdotes. I liked the one where a frail Majumdar is telling Subrata Mukherjee, minister of state for home affairs: “Do not think our movement has ended.” Majumdar was told his needs would be taken care of at the Calcutta National Medical College. What happened at the hospital and how the doctors neglected the veteran Naxalite is well documented.

The book lists the meeting of Anita, Majumdar’s daughter with her father in the Lal Bazar police lockup and how the five-minute meeting ended with some exchange of pleasantries because of the presence of several police officers in the lockup. Majumdar enquired about his family members and Anita noticed there was no oxygen cylinder in the room, an absolute necessity for Majumdar.

The book also lists what it calls the grilling sessions between the cops and Majumdar and how it was slowly, yet steadily, becoming “a heterogeneous mixture of truth and fiction”. And one of the interrogators asked Majumdar bluntly: “Do you still believe in annihilation of class enemies?”

Charubabu nodded: “Yes, I do. By class enemies I mean feudal enemies, the landowners. I fully endorse the annihilation of moneylenders besides the jotedars and landowners. I never meant annihilation indiscriminately. And I am, however, not against the annihilation of police personnel. This is inevitable as the police is the striking force of the administration. Here I would like to mention that the police did not spare my cadres and killed them indiscriminately.”

The book vividly describes the day Majumdar virtually vcollapsed inside his lockup. He was asked to sign a bundle of papers, which were said to be his statement. But Majumdar refused. And it was then he experienced an excruciating pain in his hand. “It was a known symptom but this time it seemed insurmountable. He (Majumdar) muttered the Regis Debray lines to himself—‘The underground has its own aristocracy—an aristocracy of absence—and the highest title of all is conferred by death, by murder, or execution.”

Majumdar knew the battle was far from won.

It was in the summer of April 2021 that I met up with his son, Abhijit Majumdar, in Siliguri, the north Bengal gateway to India’s northeastern states. Majumdar told me that the tea garden workers, for whom his father fought and started the Naxalite movement in 1967, continue to be in the dumps. Five decades had passed since the violent incident rocked Naxalbari, once a sleepy hamlet and now a bustling town close to the Bagdogra airport in north Bengal.

Majumdar’s death crushed the movement, and CPI(ML) was fragmented into various groups.

That is another story, except the fact that it was in 1982—the year India hosted the Asian Games—comrade Dilip Biswas, whose reported confession led to the arrest of Majumdar, was killed by members of a faction of CPI(ML).

I am still intrigued by the fact that what led the publishers to include Charu Majumdar into the list of pioneers of modern India. Maybe Majumdar helped the voiceless seek their voice, the landless seek their land, and helped a large chunk of Indians raise their voice against injustice. Injustice perpetrated not by the British rulers, but by rich and infamous landlords and zamindars who carried exploitation on their sleeves.

Loved every page, can someone turn it into a movie for the OTT platforms?