This is the first of a three-part article on the Narendra Modi government’s performance. The first article is on the prices of essential commodities, especially food.

In the tense and acerbic atmosphere of a pre-election battle wild accusations are inevitable; greying of facts is the norm and innuendoes aplenty. But when the quantum of falsity overwhelms the debate it makes a mockery of democracy.

In a desperate bid to discredit the current BJP government and dislodge Narendra Modi from power, the Prime Minister’s detractors, both political and ideological, have overstepped their brief and unleashed a vitriolic campaign of absolute negativism; a compendium of half-truths, hyperbole and outright lies that aims to sucker the voter by creating a deceptive backdrop of moral depravity, fiscal incompetence and bumbling governance.

Therefore, it is imperative that we chaff out the husk from the wheat, parse out the truth so that the voter can make an informed decision. For this we need an objective evidence-based assessment of the Modi government.

In the course of three articles I will present hard data that speak to the performance or non-performance of the Modi government.

Basically, I will attempt to answer three crucially pertinent questions:

- How affordable were essential commodities, especially food under the NDA government?

- Were we safe in our homes both from Pakistan exported terror and local disturbances?

- Could we express ourselves without fear of reprisal?

In this first article I will focus on the economy to answer the question: How affordable were essential commodities under the NDA government?

INFLATION

Instead of flummoxing the reader with esoteric indices like GDP (Gross Domestic Product) and per capita income, it is important at the outset to focus on parameters that affect our day to day life like inflation.

Inflation is academically defined as a quantitative measure of the rate at which the average price of selected goods increases over a period of time. In layman’s words, inflation refers to the increase in the prices of goods over time and means that you have to pay more money to buy a kg of onions or a pound of bread today compared to a year ago.

Inflation is expressed as a percentage and indicates the amount of decrease in the purchasing power of currency. For example, if the inflation rate is 4%, what cost 100 rupees a year ago would now be priced at 104 rupees.

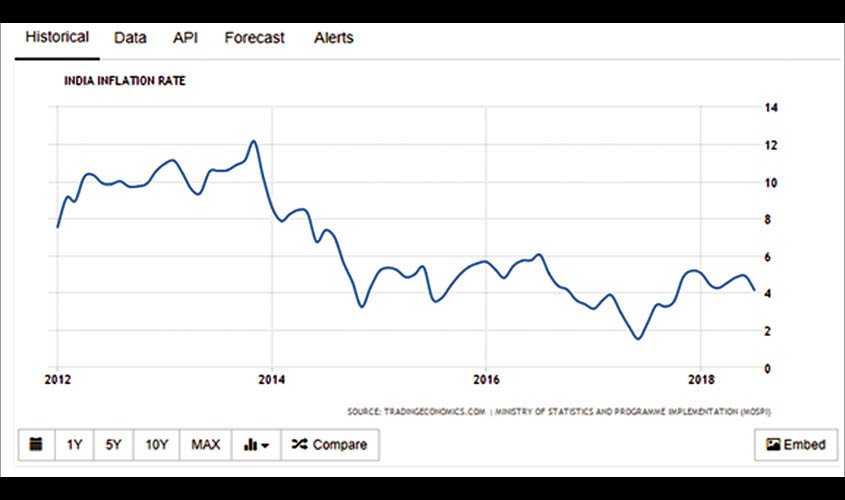

With this background information let us look at inflation in India since the NDA assumed power. Inflation has been kept in check and runs between 2%-5% compared to incredibly high levels of over 10% during the previous UPA regime (see figure 1)

When we specifically home in on food inflation, we see a similar improvement; it reached an all-time high of 14.72% in November 2013 (UPA). In December 2018, food inflation was a record low of -2.65%.

These positive economic indicators make more sense when we look at the actual price of essential commodities. A perusal of All India Average Retail and Wholesale Prices Of 22 Essential Commodities monitored by the Department of Consumer Affairs shows exceptional levels of stabilisation or even a decrease in price over a five-year period. Listed below are the prices for rice, onion and potatoes as of 20.04.19 vs 17.04.2014 as examples.

GDP

At the country level, we find that the GDP (Gross Domestic Product; a measure of the country’s economic output) has been growing at a healthy pace, save for a minor setback due to demonetisation and is expected to grow at similar levels over the next few years, pointing to a robust economy. It is important to note that even immediately after demonetisation (2016-17) the GDP growth rate was at acceptable levels and never plummeted to the dismal rate of 3.9% seen in 2008 (UPA) (see figure 4). The per capita income also rose at higher rate during the NDA regime.

In June of 2018, Ayhan Kose, Director of the Development Prospects Group at the World Bank, remarked: “India’s growth potential is about 7%, and it is currently growing at a pace above its potential.”

He attributed this to the major economic reforms and fiscal measures undertaken by the NDA government (World Bank forecasts 7.3 per cent growth for India; making it fastest growing economy, the Economic Times, 6 June 2018).

UNEMPLOYMENT

An analysis of the economy would be incomplete without addressing what has been sensationalised as the 800-pound gorilla in the room: unemployment.

Unemployment remains a major challenge for India, as a large number of youth are expected to join the job market in the coming years.

The biggest pitfall in assessing unemployment is the lack of credible data. Everyone including Modi critics agree that unemployment data in India is capricious and unreliable.

Kaushik Basu, who was the chief economic advisor to the Indian government, 2009-2012 (UPA) writes: “Measuring employment is inherently difficult in India. One reason is that the standard definition of what constitutes work…comes from industrialized nations. Yet according to various reports more than 80 percent of Indians who are working or seeking work are in the informal sector… Their activity is far more complicated for economists to measure accurately.” (Kaushik Basu, India Can Hide Unemployment Data, but Not the Truth, the NY Times, 1 February 2019.)

The present high decibel controversy based on a leaked NSSO data appears to be politically motivated rather than an inference based on incontrovertible data. The methodology adopted by the NSSO does not make for accurate statistics: “The NSSO samples the population for employment information once in five years, and since there is no saying whether the year chosen is a particularly bad one for the economy or not, it is pointless trying to claim some figure is the highest or lowest in 45 years. Maybe the best years for employment came somewhere in between its two surveys.” (R. Jagannathan. The reason India jobs data is not credible. Live Mint, 13 March 2019.)

Further Jagannathan states: “In fact, let me throw another number to prove a point—a number that comes straight from

In summary all that we can say about unemployment is that it is certainly an area of prime concern that needs to be tackled on a war footing. But with regards to the current state of unemployment, the data is too sketchy and unreliable to make definitive conclusions, let alone go into a mode of extreme panic as politically motivated alarmists have done. The contention that unemployment is at a “45 year high” is a hyper exaggeration that has no place in a rational analysis.

In conclusion, we can definitely say that the national economy is pointing in the right direction and essential commodities are at comfortable price levels. Unemployment is an area of concern but whether it is worse or better than previous years is debatable.

To be continued