Since the 1970s, there have been important political and economic pro-China vectors emanating out of Montreal and Ottawa. Since then, that have broadened to influential pro-Beijing groups across Canada.

Canada has been making headlines in India recently, and not in a good way. There were Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s statements about the farmer issue, seen in New Delhi as interference in internal affairs. And then documents were released showing that as late as 2018 Canada was allowing PLA soldiers to observe Canadian winter warfare training, seen as of use to China in its aggression against India in the Himalayas—and when the Canadian military unilaterally decided to stop the training, some in Canadian foreign affairs hit the roof.

This has raised questions about Canada’s foreign policy, and in particular, its relations with China. The questions are legitimate.

To answer them, it helps to look at three factors that helped shape the early development of China/Canada relations: missionaries, leftist sympathies combined with anti-Americanism, and the business community.

MISSIONARIES

From the end of the 19th century, Canadian missionaries went to China in relatively large numbers. Around 500 Methodist missionaries alone went to Western China, where some founded hospitals and schools, including a medical college. They became enmeshed with evolving politics in China, and had children who grew up in China, learning the languages and making friends.

During the 1930s and 1940s, some of these Canadian missionaries and missionary kids (known as Mish Kids) worked with the Nationalists of Chiang Kai-shek, and supported the Allied war effort. For example, James Endicott, born in China in 1898, became an advisor to Kai-shek and to US intelligence during World War Two.

But Endicott then grew closer to the Communists and Zhou En-lai, and worked on propaganda publications for them in China. He returned to Canada in 1947, and continued to support the Communists from there, with publications and briefing to Canadian government officials.

While Endicott was a visible pro-Communist China voice in Canada, other Mish Kids sympathetic to Mao ended up in the Canadian foreign service and quietly advocated for Canada to recognise Communist China. As early as 1950, Canada considered recognition, but then the Korean War broke out and Canada joined in on the side of the US, with Beijing backing the other side.

LEFTIST ANTI-AMERICANISM

However, by the 1960s, and especially with advent of the Vietnam War and the election of Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau (father of the current Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau) in 1968, there was more tolerance for leftist anti-Americanism in Canada politics.

Pierre Trudeau made no secret of his sympathies for communist leaders like Fidel Castro, and by the time he was elected Prime Minister, he had already visited China twice. He was there in 1949, the year the Communists took power, and then again on an official visit in 1960, when he was a labour lawyer. On the 1960s visit, he met Mao and Zhou En-lai.

Upon being elected, one of Trudeau’s priorities was recognising Beijing, something the Mish Kids in the bureaucracy were well prepared to deliver.

A stumbling block was the wording around Taiwan. Beijing wanted the agreement to state that the government in Beijing was the only legitimate government in China, and that Taiwan was an inalienable part of China. After long negotiations, they settled on the “Canada formula” that stated that the Chinese side reaffirmed that Taiwan was part of China, and Canada “took note” of that claim.

In 1970, Canada recognised China, prompting Mao to reportedly say, “now we have a friend in the US’ backyard”. Four of Canada’s early Ambassadors to China were Mish Kids. The “Canada formula” broke a diplomatic logjam, with other countries following suit with a variation on the wording.

BUSINESS

Canada was not shy about trying to do business with China even before recognition. In the early 1960s, around the time China attacked India, Canada had lent Beijing hundreds of millions of dollars for it to use to buy Canadian wheat and barley.

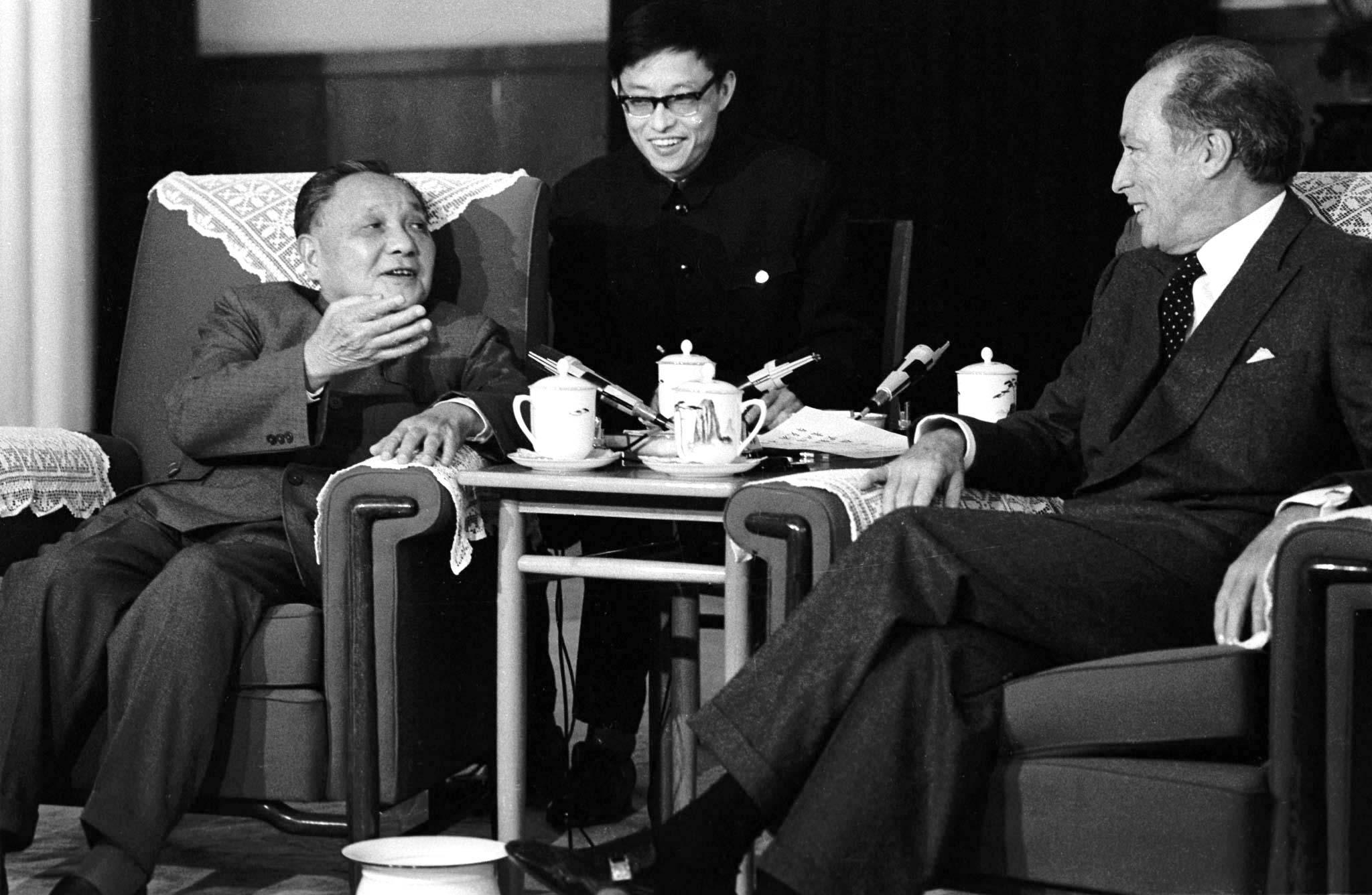

In 1973, Prime Minister Trudeau made his third trip to now diplomatically recognised China—his first as Prime Minister. He again met Mao and Zhou En-lai. A priority for Trudeau was building business ties. Part of the delegation meeting Trudeau on arrival was another Mish Kid, Paul Lin, who would prove important for developing those relations.

Lin was born in Canada in 1920 to a Chinese immigrant who had become one of the first ethnic Chinese ordained in the Anglican Church in Canada. After studies in the US, he moved to China in 1949, and became close to Zhou En-lai. He eventually returned to Canada and headed the newly created Centre for East Asian studies at McGill University in Montreal.

He was vocal in his support for Beijing, and acted as a bridge between influential elements in China and Canada. He was also “consulted” by those in the US, including emissaries of Henry Kissinger, who wished to develop linkages (later in life, Lin became Rector at a university in Macau, and conferred honorary degrees on Pierre Trudeau and Henry Kissinger).

In 1978, Lin led a ground-breaking trade delegation, and was key in the setting up of the Canada China Business Council (CCBC) that same year. Founding members of CCBC included three major Montreal-based companies, Power Corporation, Bombardier, and SNC Lavalin (of the Kerala scandal).

On the Chinese side, one of the founding members was Chinese government linked CITIC. Power Corp. not only used the opening to gain business access in China, it helped CITIC learn how to invest outside of China.

Today, Power Corp. is a multibillion dollar diversified company with deep political linkages—four Canadian Prime Ministers were affiliated in some way with Power Corp either before or after service, including Pierre Trudeau (PM from 1968-1979; 1980-1984), Brian Mulroney (PM 1984-1993), Jean Chrétien (PM 1993-2003), and Paul Martin (2003-2006). All four had political linkages to Montreal, where Power Corp. is based.

For three generations, Power Corp. has been largely run by the Desmarais family. Paul Desmarais was the first generation. He had been an advisor to Pierre Trudeau, and later Trudeau was on the board of Power Corp. Paul’s son married the daughter of former Prime Minister Jean Chrétien. Their son, Paul’s grandson, is the current Chair of the Canada China Business Council.

Less than two weeks after Canada detained Huawei executive (and daughter of the founder) Meng Wanzhou in a case related to a US extradition request, China arrested two Canadians, Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor. Since then the “two Michaels” have been victims of hostage “diplomacy”, held largely incommunicado. At a recent CCBC event, attendees applauded the Chinese representative’s call for the release of Meng, and were largely silent at the Canadian request for the release of the hostages. Holding Meng is bad for business.

TODAY

And so, since the 1970s, there have been important political and economic pro-China vectors emanating out of Montreal and Ottawa. Since then, that have broadened to influential pro-Beijing groups across Canada, in particular Toronto and Vancouver. There are the expected linkages to Chinese organised crime, attempts at strategic access, influence operations, and rob/replicate/replace business practices.

That said, “Chinese” communities are far from monolithic. Recently, a pro-Hong Kong restaurant in Toronto was vandalized by pro-Beijing elements.

However, the foreign

There have been some wins for those concerned about CCP infiltration in Canada. Recently, a Chinese company tried to invest in a Canadian gold mine in the far north that conveniently was by a strategically useful port on the Northwest Passage, and relative close to an old NORAD station. It was declined on the grounds of national security.

It feels as though in Ottawa, as in many capitals around the world, the political and business communities are keen to continue business as usual with Beijing, while the defence, security and intelligence sectors are trying to fight for a change of direction. Those voices can use all the outside support they can get given the old, deep and entrenched pro-Beijing elements in Canadian politics.

India burned through its China lobby crucible in Galwan and came out the other side a beacon for those desiring comprehensive national defence—blazing the way with app bans, FDI investigations, visa scrutiny, defence partnerships and more. Rather than criticise India’s internal issues, Canada would do well to learn from New Delhi’s external actions. Before too long, Canada will likely need India more than its Ottawa-based civil service can possibly imagine.

Cleo Paskal is a non-resident senior fellow for the Indo-Pacific at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.