There seems to be a rising belief that China’s belligerent activities, if not deterred, will have negative consequences for global peace and stability.

New Delhi/Mangalore: Following the G7 summit, China’s Global Times ran an editorial, categorically questioning the ability of the United States to establish a “united front” outside of the West. Commenting on the G7 infrastructure construction plan, seen as a counter to China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the editorial contended that it was “questionable whether it can really be carried out or achieve practical results”. More than anything else, the China challenge was a paramount factor influencing the turn of events at the recently concluded G7 and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) summits. In terms of optics, the US President has indeed scored some brownie points, pulling together some of the most powerful democratic countries in the world, including India to stand up to China’s unilateral activism and aggression in global affairs. Along with China’s intransigent and non-transparent behaviour relating to the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic, China’s aggressive military postures across the Indo-Pacific and its predatory economic practices through the BRI projects have been blatantly criticized. Leaders at the G7 summit rallied around the call for “building back better”, which has found wide support among democratic powers at least in principle. There seems to be a growing consensus on the need to join forces to regulate China’s behaviour in the international system. However, there is still lack of clarity on how exactly this has to be done.

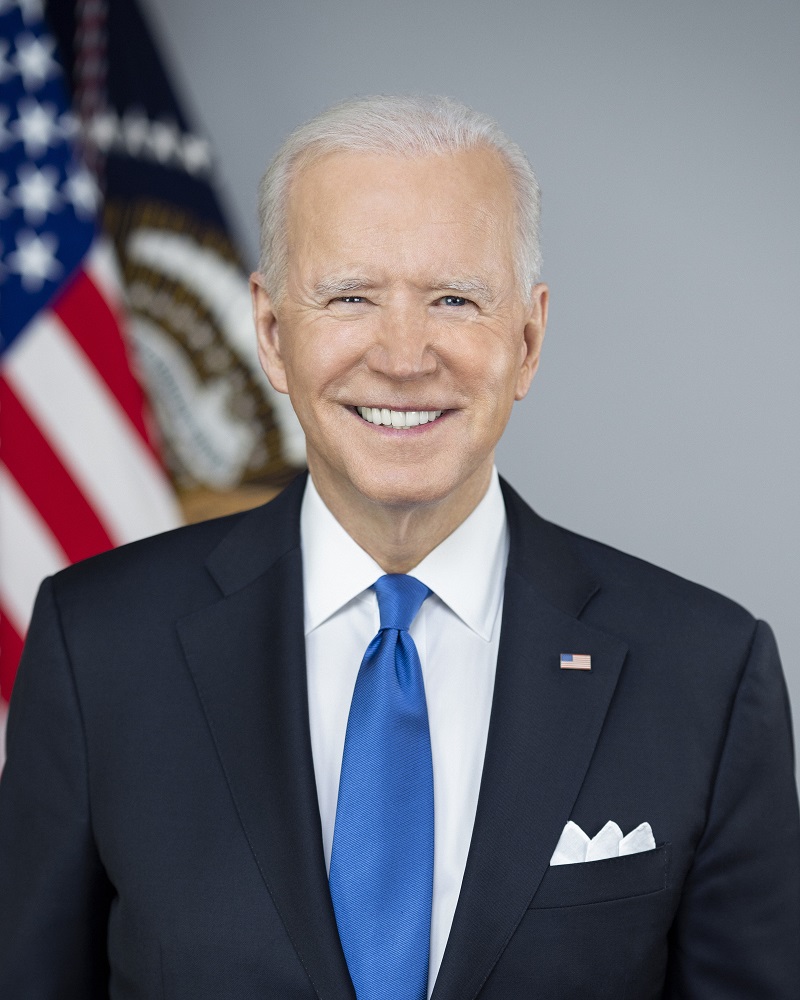

As the discourse on a post-pandemic world order surfaces among the academic, strategic and policymaking community across the world, there seems to be a rising belief that China’s belligerent activities, if not deterred, will have negative consequences for global peace and stability. In this context, it becomes imperative to assess and analyse how Biden’s commitment to restore American leadership and repair its alliance network, will translate into dealing with the China challenge, which spans across the political, economic, security and strategic landscape. On what issues the United States will play hardball with China, and on which it will handle China in a more conciliatory fashion, will be keenly followed by the rest of the world.

China’s intentions and capabilities are going to have wide and deep implications for varying facets of global and regional governance, including the need to combat climate change and managing the impact of emerging technologies. In contrast to a China-led political and economic environment, that is putting a number of countries under severe pressure to toe the Chinese line, the expectations from the Biden presidency will be not only to envision but to realise the potential of an alternative global infrastructure plan and a more transparent global supply chain and trade network. However, to play hardball with China for the United States as well its allies will be easier said than done. To find complete convergence among the China policies of the US and many of its European and Asian partners will be dependent on how interdependent their respective economies are with the Chinese economy. For the United States, there is a broader continuity and some sort of a bipartisan support as far as confronting China as a strategic competitor is concerned. However, the vagaries of domestic political changes inside the United States will affect the coherence and consistency in how the United States will negotiate with China from a position of strength.

Respective countries’ intention and ability to practice autonomy in their engagement with China, vis-à-vis America’s own intention to counter China’s rise, will produce complex permutations and combinations. Nevertheless, there is no denying that the aggressive turn in China’s behaviour seems to have accentuated during the pandemic, with military adventurism in the South China Sea, the Taiwan Straits to the India-China border. China’s influence and intentions to set the agenda in a number of multilateral institutions, more particularly at the World Health Organisation (WHO), with respect to criticism about its handling of the coronavirus outbreak, has shown the imperative for the international community to get its act together and help shape a rules-based order. Communiques from the G7 and the NATO summits have been quite revealing about the intention of the US and its NATO allies to collaborate with other like-minded Indo-Pacific countries to confront challenges emerging from China’s rise across the spectrum, including cyberwarfare, artificial intelligence and disinformation. The question remains: How is President Joe Biden’s tough stance on China different from that of his predecessor President Trump? While Trump too talked tough on China, slapping sanctions and calling out China’s military coercion, his efforts to take along America’s allies and partners, were found wanting. Perhaps that is where Biden will be different, who will perhaps be taking a multilateral route to tackling China challenge, collaborating more with American allies and partners towards a democratic concert of powers.

China’s strategic ambitions have been enlarging. It wants to lead the global order and replace the US and the West from the global landscape and the existing world order. However, the rest of the world has always doubted the intentions and credentials of China. It is, generally believed, among comity of nations that China has been transitioning from assertiveness to aggressiveness. There seems to be an absolute lack of trust and confidence in reposing faith in China. Will the United States evolve a strategy by which it can call China’s bluff? The pandemic has provided sufficient impetus for the rest of the world to come together and deal with China sternly. The US has to play a dominant role in building a narrative which would restrict China’s growing influence and contain its ambitions to change the global order. The new global order has to be built by the responsible nations and not China. China has proved detrimental to global peace and stability. It will remain antithetical to global interests.

Arvind Kumar is Professor at the School of International Studies (SIS), JNU and is also the Chairman of the Centre for Canadian, US and Latin American Studies at SIS, JNU. Monish Tourangbam teaches Geopolitics and International Relations at Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE), Manipal.