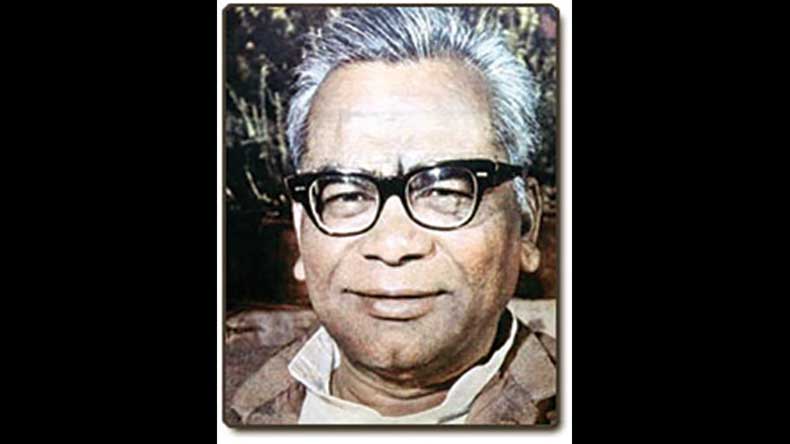

I have always believed that somehow, the philosophy and principles of Dr Ram Manohar Lohia, the socialist leader, have never received due recognition. Maybe he was too brilliant in his speeches; he certainly insisted on moral principles in public life, namely that politicians’ words must match his deeds and there must be no forgiveness of hypocrisy in politics.

That is why I am responding to the column, Four ministers key to Modi’s success written by well respected political commentator, Professor M.D. Nalapat in The Sunday Guardian of 2 -October 2016.

His first comment was praising Morarji Desai when in 1977 he became the Prime Minister not to delete English from administration and education under pressure from the followers of Dr Lohia (incidentally Dr Lohia had died in 1967). Let it also be remembered it was Dr Lohia’s anti-Congressism, which in 1967 led to non Congress governments in eight or nine states in India. It was to the credit of Dr Lohia that he understood that unless the backbone of Congress hegemony was not broken, India could not really become a democratic socialist state.

In presenting Dr Lohia as Hindi zealot even against the other languages of India is to do great injustice to his philosophy. No doubt Dr Lohia was against the exclusive small caste of English knowing people being the rulers. He treated all languages of India including Hindi on an equal footing.

Let me give his philosophy of Angrezi Hatao (remove English) in his own words. “It is now impossible to banish the public use of English without the desire of the people. The policy of removal of English gradually, which has been adopted by the Government of India, is proving more dangerous than the policy of retaining English forever. The chief problem is the removal of English and not the establishment of Hindi. This clarification is necessary, for the non-Hindi speaking states like Mysore, Bengal; Tamilnadu should have the option not to use Hindi at all. They may use their own language but they also must remove English.

Dr Lohia’s contribution to understanding the damage done to Indian thought and history by caste, deserves respect.

“A correct language policy has to be evolved. Hindi should be the language of the central government

I can recall his pain when he read about the misunderstanding of his position on languages and which caused the setback to the development of national languages and correct language policy. It was sometime in the 1960s when I had the privilege of Dr Lohia coming on a socialist party programme to Chandigarh. He stayed at my residence—at that time I was the chair person of the socialist party (Punjab branch).

I remember a very pained Lohia when he was staying with me at Chandigarh. News had come that the anti-Hindi agitators in the South had burnt Hindi periodicals. I still see him sitting quietly in the verandah lawn with a sad look on his face and telling me softly, “Rajindar, the movement for Hindi is dead. When it will be revived I do not know.” Dr Lohia was not a Hindi chauvinist. He was for state languages. He believed that the presence of an English knowing minority, who are even now only 4%, will never let the poor become the vehicle of politics. He accepted the supremacy of Tamil and Telegu languages in the states. He was not against English language as such. He was of the view that in no democratic state, bureaucracy can work effectively for people’s policies unless the administration is carried out in the poor people’s language.

I accept that Dr Ambedkar’s fight for annihilation of castes is one of the most important contributions toward our political thought. But I believe—and I mean no disrespect to Dr Ambedkar’s contribution—that Dr Lohia’s contribution to understanding the damage done to Indian thought and history by caste, deserves equal respect.

Dr Lohia unhesitatingly praised Dr Ambedkar for his unique contribution to the cause of the poor and especially Dalits. In a letter addressed to another socialist leader, Madhu Limaye on hearing of the death of Dr Ambedkar, he wrote “you can well understand my sorrow at Dr Ambedkar’s sudden death. Dr Ambedkar was to me a great man in Indian politics and apart from Gandhiji is as great as the greatest caste Hindu. This fact has always given me solace and confidence that the caste system of Hinduism can one day be destroyed.” He had expressed the hope “that the Scheduled Caste Federation Forum of Dr Ambedkar will contribute to have the symbol of Dr Ambedkar for homage and his independence… Dr Ambedkar…would be leader of all Indians and not Dalits only.”

Dr Lohia’s greatest contribution to the political thought is the role of the castes in India. He was the first political thinker to put forward the startling truth that castes and class are interchangeable in our Indian conditions. The gap between the hundred million Dvijas on the one side, and the two hundred million Dalits on the other is so wide that no political party has as yet undertaken to fill it up. Political life in India is not clean. Lohia wrote, “Nepotism, jobbery, opportunism, flattery, non-adherence to truth and a tendency to twist doctrines to suit particular motives are some of the traits of Dvija leadership. These traits will remain with the Dvijas unless they make a conscious effort to bridge the gulf between themselves and the Dalits. The Dalit too has his shortcomings. He has an even narrower sectarian outlook. Once in office, the Dalit tries to perpetuate himself by having recourse” to doubtful methods. He must achieve a broadness of outlook.

Dr Lohia nevertheless concluded in spite of all this, not only must the Dalits be now pushed to positions of power and leadership but sustained efforts should be made to enable them to imbibe a broad cultural outlook so that the stagnant waters of the country’s social life may flow away and the Dvijas and Dalits both be made to shed their weaknesses. It is futile to talk of revolutionary politics unaccompanied by efforts for social change. Only that political party has a future now in the country, which would make itself the spearhead of this social revolution and by its organisation herald a new dawn.

The system of castes is a terrifying force of stability and against change, a force that stabilises all current meanness, dishonour and lie. An unholy fear prevails, lest, if some meanness or lie were to tumble the whole structure might topple.

It is meaningless to talk of equality while maintaining separate castes. Castes have to be abolished. Even their nomenclatures should go

Rajindar Sachar is a retired Justice.