China believes that India not joining the RCEP is temporary, and that it is willing to continue to negotiate and iron out issues facing the negotiations with India.

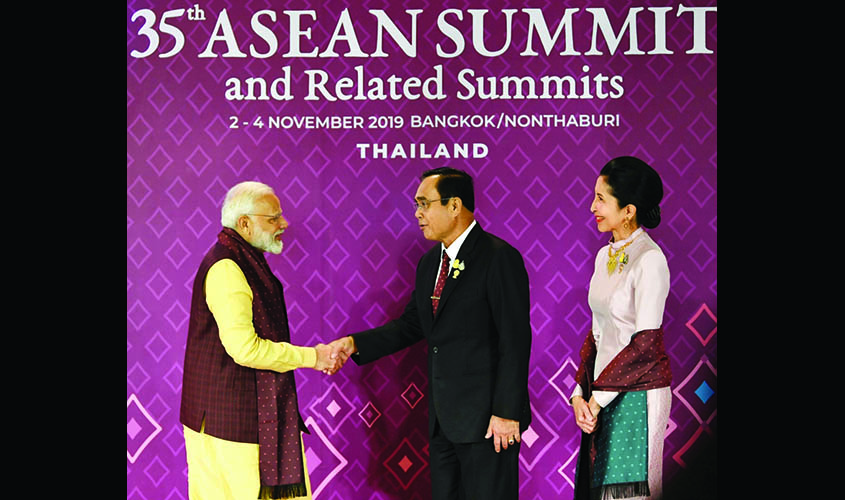

On 4 November 2019, after negotiating for seven years, India temporarily decided not to sign the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) until it satisfactorily addressed “India’s outstanding issues and concerns”, even though all the other 15 countries (10 ASEAN and six Asia-Pacific including China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand) agreed on the “text based negotiations” and declared that they were ready to sign the deal in 2020. What are India’s concerns? Why did it back out even after participating in all the 28 negotiations, nine ministerial meetings and three summits, and how is China reacting to India’s decision?

In the words of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, since the agreement doesn’t augur well for the interests of all Indians, therefore, “neither the talisman of Gandhiji nor my own conscience permits me to join RCEP.” What are these interests? The foremost of India’s concern is its burgeoning trade deficit of $53.5 billion with China, $21.8 billion with ASEAN, $12 billion with Korea, $9.6 billion with Australia, and $8 billion with Japan. If India signs the RCEP, India would be forced to reduce duties on around 90% of its imports over the next 15 years, therefore, apprehensive of Chinese products flooding the Indian market in absence of an auto-trigger mechanism that India had sought to check the imports but was rejected. However, the seventh ministerial meeting in Vietnam revealed that India was willing to reduce tariffs on 28% of Chinese products immediately, and the remaining in a phased manner over 15 years.

India is also concerned about China circumventing the rule of origin, which seemingly has not been addressed either. Dairy products from Australia and New Zealand could adversely impact the domestic dairy industry. Other industries such as steel and textiles have also sought protection. Secondly, India has sought greater movement of labour and services to RCEP countries, which seems to have fallen through in the face of stringent immigration laws in these countries. Thirdly, India has sought 2014 as the base year for tariff reduction rather than 2013 when its import duties were lower. Fourthly, India’s request for exemption from Ratchet obligations (raising tariffs after signing the deal) also hit a wall. Fifthly, the protectionist pitch raised by opposition parties and the ruling party’s parent body the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) has also made the government cautious about saying yes to the deal without enough safeguards. Finally, the economic slowdown in India manifested in the plummeting growth rate and rising unemployment could also be held responsible for India refusing to sign the deal.

How has China reacted to India’s negotiations and refusal to sign the deal? While most of the writings on the matter agree with the above proposition, however, these have also offered varied insights. For example, many articles have levelled India as a defiant “nail house” (dingzihu) resisting development around it. If India joins the RCEP, the largest ever free trade zone will cover 45% of the world’s population, nearly 40% of the world’s GDP, about 30% of total world trade, and about 36% of global foreign direct investment. The headline of a column in Kline.123.com.cn, on 5 November reads, “India ‘a nail house’ for 7 years has opted out of RCEP”. It says that India’s decision was influenced by the pitch made by the US Secretary of Commerce during the Indo-Pacific Business Forum held on 4 November 2019. Arguing for India’s participation, the article says that the $23 trillion GDP of the bloc will essentially pave way for the Indian economy to take off and reap the demographic dividend. If it doesn’t, the same will become a population trap and aggravate India’s economic situation further. In the same vein the Global Times also writes that joining RCEP would have been beneficial to India, just as China’s entry into the WTO (2001) “forced China’s industrial progress and greatly promoted China’s industrialization process”.

Secondly, India lacking a competitive industrial structure and relatively low national capacity has also been listed as one of the reasons by academicians and reporters like Mao Keji of Yunan Academy of Social Sciences and Yuan Rongji of the People’s Daily. They believe it is this industrial structure, which has made it difficult for India to transform reforms with openness like China. This has been proved by India’s FTAs with other member countries like Australia, Korea and Japan. For example, they argue, trade deficit between India and South Korea has shot up from $5 billion in 2009 to $12 billion in fiscal year 2018-19. Therefore, structural reforms are required in order to attract foreign investment, promote economic growth and create employment, which in turn would provide a breathing space for domestic enterprises. The RCEP, they argue, would have had a positive effect on improving the above goals, however, “the most trouble-free choice” for the government to neutralise pressure from various interest groups undoubtedly is to step out of the RCEP.

Thirdly, Chinese scholars argue that India backing out of RCEP is owing to the excessive politicisation of India’s economic problems. They have cited the examples of Swadeshi Jagran Manch boycotting foreign products and nationalist parties and their outfits advocating swadesi, which they feel make India extremely protectionist and a reluctant player to join the global supply chains. In such a domestic situation, “politicians can only choose short-term gains, allowing economic gains and long-term benefits to go by”. In this regard, they give the example of Modi saying “India staying out of the RCEP is in line with popular public opinion”.

Fourthly, geopolitically, if India is neither a member of the TPP nor RCEP, what will happen to India’s “Indo-Pacific strategy”? Undoubtedly, the Chinese scholars have not spelled it out. Nonetheless, they admit that without an economic heft any talk of any strategy is empty talk. It is the interdependence and the economic integration that make you an important stakeholder, not if you sit on the fence. In this context, some Chinese reports argue that India opted out of RCEP at the behest of the US.

Finally, China believes that the Indo-Pacific region is increasingly becoming the fulcrum of global geo-economics and geopolitics. China is deeply integrated with the region. The RCEP will undoubtedly consolidate its leading position in the region. China believes that India not joining the RCEP is temporary, and that China is willing to continue to negotiate and iron out issues facing the negotiations with India in the spirit of mutual understanding and mutual accommodation. China will welcome India’s participation in the agreement at the earliest. It has stated that India not signing the RCEP will not have a negative impact on China-India economic relations.

B.R. Deepak is Professor of Chinese Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.