Nehru made freedom of speech conditional on the will of the bureaucracy.

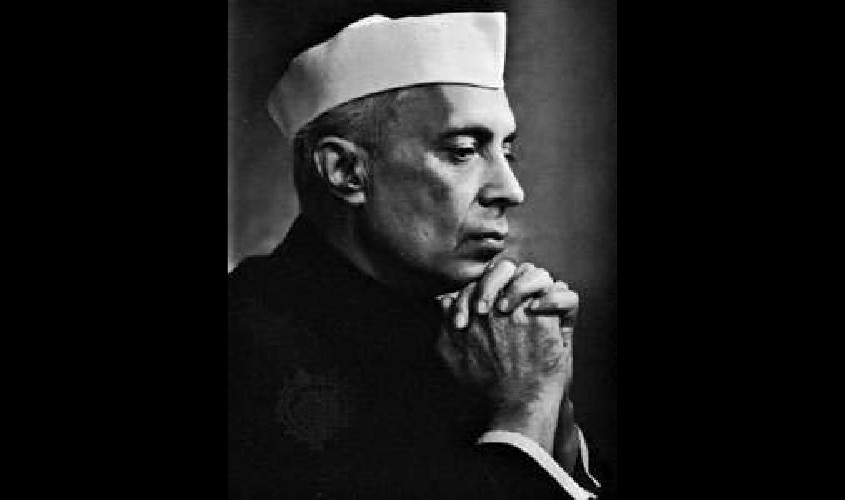

In a democracy, governments cannot be equated with the people. During British rule, any effort against that government was treated as an attack on India and punished, as though the “nation” comprised only of the British. It took only 16 months before the Constitution of India was amended to ensure that the maxim of “Government equals the Nation” once again took effect in jurisprudence. Mao Zedong brought together into a single country more territory than China had effectively controlled throughout its long history, while those who led India after the British left accepted a cruelly truncated subcontinent with merely a rhetorical shrug (“not wholly or in full measure but very substantially”). Abraham Lincoln waged war on the seceding states that formed the Confederacy in order to keep the country united, while Nehru was horrified at even the thought of bringing together what had been torn to pieces. Tripurdaman Singh has written a book on the first amendment to the Constitution of India, an episode which merits inclusion in school and university syllabi. The book, Sixteen Stormy Days, narrates the methodical way in which Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru overturned the freedoms that had been guaranteed to the people of India by the foundational document that had been unanimously approved by the Constituent Assembly just 16 months earlier. Freedom of speech was made conditional on the will of the bureaucracy, while lapsed British-era powers of the state to take away the wealth and liberty of the citizen were reinstated. Sections 124A and 153A of the Indian Penal Code were brought back into life, while Article 15 assuring equality of every citizen before the law had several exceptions tacked on to it. The government was in effect identified as the nation, which meant that criticism of the government was tantamount to an attack on the state. And as Jawaharlal Nehru in actuality was the government, criticism of the Prime Minister was treated as anti-state and anti-national. Once the First Amendment to the Constitution got passed in 1951, the colonial overlay of the governance mechanism regained its supremacy, a dominance that it has since never lost, despite 73 years after “freedom”. To this day, the civil service has mastery over civil society much the way it did during the days of British rule. It seems futile

In this era, where jail time is the fate of many who are less than respectful to those in authority, it needs to be remembered that such a trend began during the very first years of freedom. Given the curbs to freedom of expression caused by the First Amendment, was it any wonder that textbooks and the media soon got filled with encomiums to Nehru? Or that nascent efforts at examining the causes and legacy of Partition were soon replaced with the government-approved version of events, which was that the vivisection was inevitable and indeed, desirable? The government got back the licence it enjoyed during the colonial period to curtail multiple freedoms of citizens on the grounds of “public interest” (where the well-connected constituted the “public”). The only individual who had the will and the stature to stand up to Nehru—Vallabhbhai Patel—died towards the close of 1950, and from then onwards, Nehru began to insert the government into the daily lives of citizens so as to denude them of rights, including liberty and property. Security of property is essential to rapid development and to the creation of an entrepreneurial rather than a carpetbagger class. The fragility of the right to property in India has caused several well-connected businesspersons in India not to look for a return on equity but a return of equity. In other words, by under-invoicing, over-invoicing and in numerous other crooked ways, to soon get back what money of their own they had invested in an enterprise. From then onwards, their only motivation is to grab as much pecuniary and other benefits from an enterprise as the bureaucrats and politicians allow. Another side effect of the perpetuation of the colonial system of governance has been the propensity of HNIs to send money out of the country rather than grow it within India. Small wonder that there has been such a rush to the door opened by the Insolvency & Bankruptcy Code (IBC). Several thousand enterprises of varying size are now gleefully enmeshed in the coils of the IBC, especially those that have borrowed large sums of money from financial institutions without any expectation on the part of either lender and borrower that these sums would get repaid. While Vijay Mallya’s reported offer of paying back 80% of the moneys he owed was rejected in favour of a UK court proceeding of indeterminate result, secretive hedge funds registered in external banking havens have been successful in persuading banks to agree to 80% or even 90% “haircuts” of select loans. In very short order, these funds have managed to dispose of the same loans at a huge profit, a path to wealth through bank NPAs that gained traction during the period when P. Chidambaram was Finance Minister. The saving grace is that in this era of internet banking, any permanent scrubbing away of transaction records has become much more difficult than during the days when a fire could fortuitously break out and burn records to a crisp. Sometime in the future, those who are taking advantage of the immense powers of the bureaucracy to scam their way to mega wealth will get exposed, just as sometime in the future, the young of India will succeed in their demand that the colonial edifice of control get off their backs. Someday, the Constitution of India will return to its original form, in which the people will no longer be bullied by government into surrendering their freedom and their possessions. A book such as Sixteen Stormy Years would have never been allowed to get distributed in India during the days when Nehru, that exemplar of the freedom of the individual as defined by freedom of an individual to rule over the rest (and the ideology he spawned), was in charge of the mechanism of governance. These, fortunately, are days when criticism of Nehru is unlikely to lead to the penal consequences that have accompanied condemnatory writings and speeches about VVIPs in India ever since the First Amendment to the Constitution of India got passed in 1951.