Patel’s carrot and stick policy not merely involved taking the leadership into confidence but also recognizing the realities on the ground.

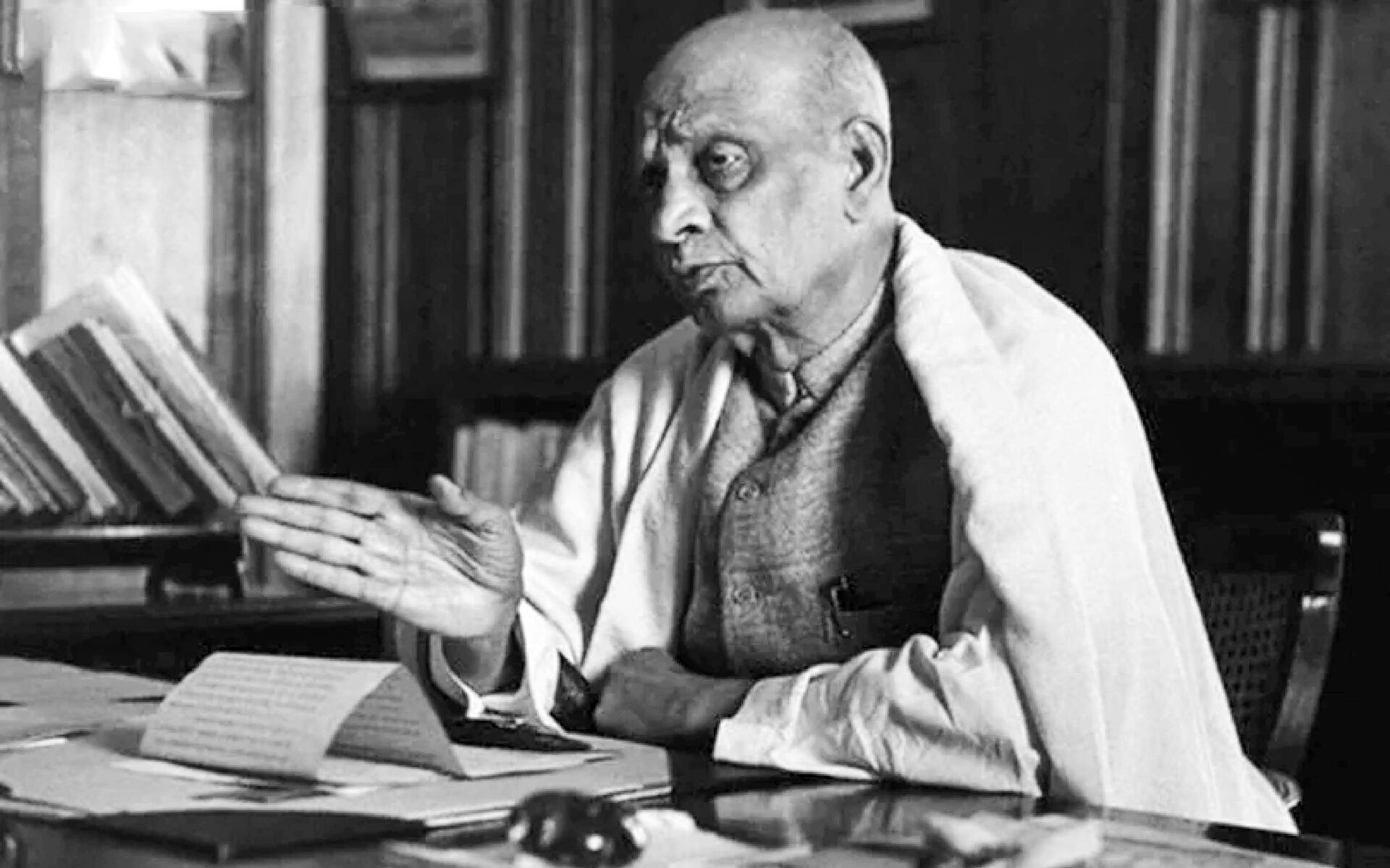

Kutch to Kohima, Kargil to Kanyakumari—if we can travel freely today across the beautiful and bountiful lands of India, it is because of one man, the Iron Man of India, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. He did something unparalleled in history, with the integration of over 560 princely states. He used Kautilya and Vidyaranya’s wisdom and Chattrapati Shivaji Maharaj’s courage to achieve the great feat of uniting India after Independence. He is an unsung hero, and rightly we need to know more about him. His 150th birth anniversary began on 31 October 2024 and was celebrated rightly as National Unity day.

UNIFYING BHARAT

Enters Sardar Patel, the first Home Minister of the interim government formed in the wake of Independence in 1947. Ideally, the princely states and these principalities would be asked to make their choices. Yet, the reality was much more complex and granular. By and large, some of the kings and rulers of these princely states were either forthright to join India, some were indecisive, and others were not supportive.

For Patel, this was a challenge that, according to his strategies, needed two approaches: carrot and stick. Remember, the challenge to integrate was indeed a political matter, but it was also a cultural and social matter, given the diversity of languages, religions, beliefs, and values in these different principalities and princely states. Pakistan, the newly formed state under the banner of Islam, was actively pursuing its own negotiations and strategies to bring these principalities under its control. Smaller princely states were brought under Indian sovereignty through old-fashioned diplomacy, with kings and rulers given incentives and appeals to form the legacy of the millennia-old idea of Bharat. The major problem stood with critical states of Jodhpur, Junagarh, Hyderabad, Travancore, and Kashmir.

The intense negotiations with Jodhpur were in June 1947, months before Independence and days after Patel became the Home Minister. Jodhpur, ready to join Pakistan, was persuaded to remain under Indian sovereignty. The case of Travancore was crucial, for it was a very large state with an entirely different cultural history. The king was determined for independence; therefore, bringing Travancore was a critical accomplishment given its normative consequences on other independence-seeking princely states. The Patel diplomacy again got the job done in July 1947.

The case of Junagarh was different, for the ruler was determined to join Pakistan much more staunchly than Jodhpur, and negotiations between him and Pakistan had reached far to ensure that outcome. Yet, what was unique about Junagarh was the split between the ruler’s predilection with Pakistan and the people’s view on the ground, which stood openly to join the Indian state. Patel’s measures to ensure this outcome was done by conducting a plebiscite in Junagarh in February 1948, and the overwhelming majority chose to remain with India.

Meanwhile, the Nizam of Hyderabad signed a Standstill Agreement with India to sustain the status quo of not joining either side. However, the state became marred with communal tensions and persecution that needed decisive force to deal with. The inability and lack of intention of the Nizam, followed by his predilection towards Pakistan, meant that Patel had to use force. Thus came Operation Polo by the Indian Army, and on 17 September 1948, a ceasefire was announced, and Hyderabad joined India.

The case of Kashmir was not entirely a prerogative of Patel as Nehru took personal interventions. The indecisive Raja Hari Singh of Kashmir reached out to India after Pakistan attacked in October 1947, and through an Instrument of Accession, India extended its help. The following negotiations with constitutional exceptions to Kashmir and ill-judgment to reach the United Nations made things much more complex. Still, if anything, when Patel’s strategies vis-à-vis other princely states are considered, had he handled Kashmir without interference, the prolonged misery of the Kashmiri people and the Indian state could have been avoided.

LEARNING FROM PATEL

Sardar Patel was indeed the man of the people, and his epitaph of “Sardar” (chief) (given to him after the Bardoli Satyagraha of 1928) reflects how contemporary Indians viewed him. The recent reinvigoration of interests regarding Patel is necessarily a crucial correction to historical amnesia about his legacy. The Statue of Unity, the world’s tallest statue, is the symbolic representation of how tall Patel stood in making a united India, which we today take for granted. Patel’s recognition and respect for diversity enabled him to forge unity, a lesson for diplomacy and even individual lives. His carrot and stick policy not merely involved taking the leadership into confidence but also recognizing the realities on the ground.

Recently, we see his approach being used in India’s neighbourhood policy, especially in case of Maldives. President Mohamed Muizzu, who was staunchly anti-India, changed his view entirely through diplomatic tact. For such reasons, Patel’s unification project must be read, taught and widely disseminated. The celebration of Rashtriya Ekta Diwas and Unity Day Parade is a notable commemoration of his contribution but more efforts are required in this direction.

Present day India owes an immeasurable debt of gratitude to the vision, tact, diplomacy and pragmatic approach of the Sardar in preventing the balkanization of the country and merger of more than 560 princely states with the Union of India. What makes this stupendous integration most remarkable is that it was achieved without any bloodshed. Perhaps for such reasons, Prime Minister Narendra Modi spoke about “One Nation, One Election” and “One Nation, One Civil Code” during his speech earlier on 31 October at the Unity Day Parade. There is no way to honour Patel’s legacy than upholding his ideas and ideals to galvanize Bharatiyas under the idea of Bharat, for Sardar was the builder and consolidator of New India.

* Prof. Santishree Dhulipudi Pandit is the Vice Chancellor of JNU.