The Maoist leader and present Prime Minister, Prachanda was to admit later that the ISI had offered the hand of friendship and cooperation to the Maoists, but he had declined it ‘out of self respect’.

India-Canada relations are going through a rough patch after the Canadian Prime Minister’s allegation that there was “credible evidence” of involvement of Indian government agencies in the assassination of Khalistani activist Hardeep Singh Nijjar on Canadian soil.

There has also been “informed speculation” in India that Pakistan’s ISI was actually behind Nijjar’s killing with the aim of straining India-Canada ties, and as he was “resisting their pressure to support gangsters who had arrived in the country.” This has yet to gain traction, possibly because it seems belated and on the face of it, far-fetched.

Yet the fact is that in the strange underworld in which “The Nexus” operates, what appears to be far-fetched is sometimes the reality.

That was certainly the case when this writer served as India’s Ambassador to Nepal for five and a half years, from 1995 to 2000.

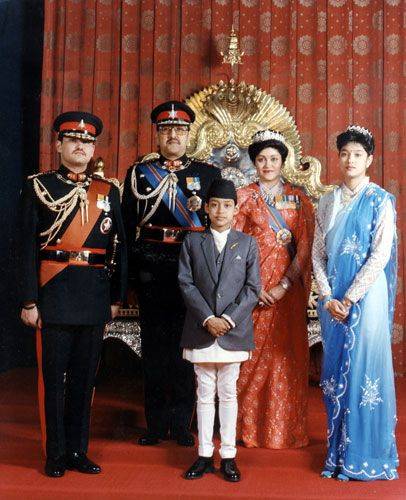

With Nepal’s democracy still in the process of settling down, a Communist-led government which had come to power on an openly anti-India campaign, and King Birendra with whom India’s relations had been tense for two decades and who had been compelled by an India-supported mass agitation to cede absolute power and become a constitutional monarch, India was worried about a major escalation in anti-India activity through Nepal.

The first part of my tenure was full of positive and exciting events, marked by major strides in cooperation in all sectors, including security.

Then chronic political instability, poor governance, and vote bank politics took centre stage in Kathmandu. Birendra’s influence and popularity increased with each passing day.

The Maoist movement (targeting the special relationship with India, the monarchy and multiparty democracy) launched in 1996 took root and expanded its influence over much of rural Nepal.

Relations with India were fortunately not affected. However, The Nexus, taking advantage of lax cross-border controls in place on both sides, increased multifold its smuggling and terrorist-related activities.

Many tragic incidents—including bombings, the hijacking of IC 814, the Hrithik Roshan riots—took place, and involvement of The Nexus and Pakistani diplomats and front companies and NGOs was repeatedly exposed.

There was excellent cooperation from the government of the day, as also when needed, of the Palace.

Nepali intelligence or their political bosses were sometimes a bit timid in exposing Pakistan’s complicity or in overruling its assertions of diplomatic immunity when it came to preventive or punitive action. In such cases in particular, quiet Palace intervention would prove to be very useful.

I recall the Pakistan Ambassador calling on me and asking, somewhat cheekily, “Achha, toh ab aap aur Raja ISI-YSI khatam karne wale hain? (So now India and the Palace are out to finish the ISI?)”

King Birendra had his own reasons to worry, apart from genuinely wishing to improve relations with India by doing his bit wherever it was necessary and possible, including on our security concerns.

All along the open border in the Tarai, Islamic fundamentalist groups were spreading propaganda against Nepal’s identity as a Hindu Kingdom, as it made their work more difficult. NGOs with foreign funding had been allowed by successive permissive governments to operate freely. Vote-bank considerations often took precedence over Indian sensitivities.

The Pakistan Ambassador was openly seeking funds for certain front outfits sympathetic to the Khalistani cause. Nepal has a several-centuries old Sikh heritage. I was a regular visitor to Sikh gurdwara functions, and often got important information from Sikhs long settled in Nepal and their Nepali Hindu friends about attempts to hurt Indian interests.

Western diplomats were alert and sympathetic about the spread of Islamic fundamentalism in the Tarai. But they did not seem to know or care much about the long-term threat of revival of Khalistani terrorism, perhaps because it did not figure much in western countries as a direct threat to them. That dangerous attitude persists to this day. In contrast, Birendra took revival of Khalistani activity with full seriousness.

Birendra was also increasingly worried that the Maoists and ISI would get in touch with, and reinforce each other against the monarchy as well as their “other common enemies”. (The Maoist leader and present Prime Minister, Prachanda was to publicly admit later that the ISI had indeed offered the hand of friendship and cooperation to the Maoists on more than one occasion, but he had declined it “out of self respect”).

It was a highly complex situation marked by violence, destructive competition and desperate secret searches for compromises between pairs of players seeking partnership while striving for power at any cost.

The Maoists, encouraged by Birendra’s reluctance to unleash that Army against them, reached out to Birendra. India did not object, on condition that multiparty democracy would be retained.

The Nexus had clear objectives: cutting the monarchy down to size, creating tensions between India and Nepal, neutralizing Nepal’s Hindu identity, preventing a rapprochement between the Maoists and the monarchy.

A Palace-Maoist dialogue was set to begin in April 2001. Crown Prince Dipendra and Birendra’s brother Prince Gyanendra were said to be on board.

On the evening of 1 June 2001, the Birendra line ended with the murder, among others of the King, Queen, and their two younger children. Crown Prince Dipendra allegedly shot himself after killing all the others.

The swift cleaning up of the crime scene, destruction of the building where the killings took place, cremation of bodies without post mortem—there were as many unanswered questions as there were conspiracy theories.

Prime suspects, other than the Crown Prince, included Prince Gyanendra, who had escaped the massacre due to his absence in Pokhara, and who later became King, and of course India, although there was no particular logic to the allegation that India would have an interest in ending Birendra’s life given the now excellent relationship with him.

Among those accusing India were Maoist leaders, who suspected that India did not want Birendra to reach an understanding with the Maoists as it would have ended its own influence in Nepal’s internal affairs.

In a section of the book “Kathmandu Chronicles: Repurposing India-Nepal Relations” to be published shortly by Penguin Random House, I have explained in detail the real background to the tragedy as I know it. The section is entitled “Diplomatic Gleanings: A First Person Account”. Atul K. Thakur is my co-author for the other two sections.

The clinching evidence points very clearly towards involvement of The Nexus in the massacre. Birendra paid with his life for playing a part in exposing the Pakistan hand behind terrorist-related and large scale smuggling activities in Nepal, the humiliation of Pakistan embassy diplomats, and cooperating with India against Nexus activities.

Coming back to Canada, the current episode shows that The Nexus is as skilful today in manipulating vote-bank politics to further its interests—promoting terrorism, creating divisions within India, weakening institutions seen as hostile to its objectives—as it was over twenty years ago.

Its capacity to hurt India has not been reduced due to Pakistan’s internal problems; it has huge resources at its disposal thanks to the international smuggling industry in arms and drugs.

It does not matter whether the “base country” from which operations are planned is a full-fledged democracy like Canada or an emerging one like the Nepal of the 90s. The only difference seems to be that The Nexus has mastered techniques to stay away from the limelight; in Nepal, its agents, including ISI operatives and Pakistani diplomats were constantly getting exposed, whereas today much of the media glare is on Canada, India and Khalistan.

The question unanswered is why Trudeau should be backing a proclaimed terrorist, the head of the Khalistan Tiger Force, who had nearly a dozen terror cases and an Interpol Red Corner Notice against him. Is it simply vote bank politics? Or is there another explanation which appears “far-fetched” today but may turn out to be the reality tomorrow?

- K.V. Rajan is a former Secretary, Ministry of External Affairs. “Kathmandu Chronicles” will hit the stands in 2024.