An environment of mistrust and insecurity has existed from the very inception of the Republic of India and the People’s Republic of China.

The interconnected history of India and China and the circulatory movement of ideas, people, technologies and commodities has been well documented in both textual and oral traditions of the two countries. There is no doubt that this uninterrupted dialogue not only enriched their respective civilizations but also benefited various neighbouring polities. However, the legacies inherited from British colonial rule in India and Manchu rule in China, combined with both nations’ reluctance to seek compromise, fostered an environment of mistrust and insecurity from the very inception of the Republic of India and the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

TROUBLED LEGACIES AND EQUILIBRIUM

As India hurried to denounce Chiang Kai-shek’s Republic of China (ROC) and recognize the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on April 1, 1950, it continued to follow British policies on Tibet. In its foreign policy discourse—from the Asian Relations Conference (March-April 1947) to the signing of the “Agreement Between the Republic of India and the People’s Republic of China on Trade and Intercourse Between the Tibet Region of China and India” in 1954—India referred to Tibet as a “sovereign state” or, at most, as being

Both had an opportunity to resolve the border issue in 1954, but as both sides remained firm in their positions, they not only missed this chance but also failed to seize another opportunity in 1960. During his visit to India amid simmering hostilities, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai hinted at resolving the border dispute based on “historical context and existing realities.” However, the flight of the Dalai Lama to India further exacerbated tensions, ultimately leading to the 1962 border war and a prolonged diplomatic freeze. In 1980, China suggested the “East-West Swap” or the “package deal,” but the sectoral approach stalled progress. Nevertheless, as both nations shifted their focus to economic development, a gradual equilibrium was established.

The equilibrium was founded on the premise that both nations were at a similar stage of development and, therefore, needed to fully leverage their complementarities and potential. Based on this understanding, they signed a series of confidence-building measures (1993, 1996, 2005, 2012, 2013) to stabilize the border and enhance security. This cooperation enabled them to align on various issues of mutual concern and played a key role in establishing multilateral mechanisms such as BRICS, AIIB, NDB, and SCO. It marked a golden era of bilateral camaraderie, unprecedented since the India-China “brotherhood” of the 1950s. Both countries emphasized that their shared interests far outweighed their differences and that there was ample space for them to grow and rise together.

POWER SHIFT

However, as the balance of power shifted in China’s favour following its economic rise, the equilibrium proved to be temporary and gradually eroded, with China adopting an increasingly assertive stance along the border. To counter its economic, technological, and military asymmetry with China, India strengthened its security partnerships with the US and its allies. Moving away from its previously cautious approach toward US-led groupings, India became an active participant in key elements of the US Indo-Pacific strategy, including the Quad, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI), India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), India, Israel, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States (U2I2) grouping, and the India-US 2+2 dialogue. China perceived these initiatives as efforts to contain its rise and diminish its influence across various regions.

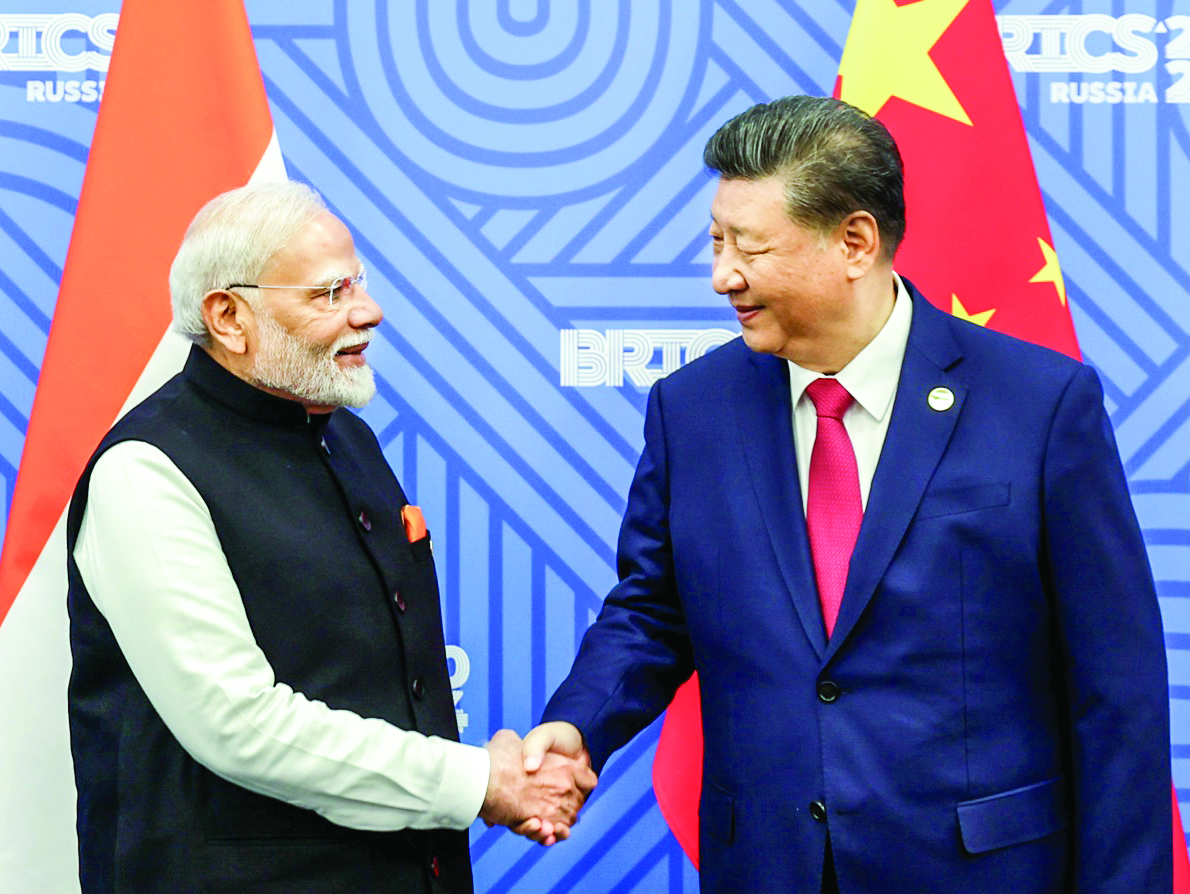

The trust deficit between India and China is no longer confined to the Himalayas—it now extends into multiple domains, including the broader Indo-Pacific. While elements of mistrust, competition, and rivalry had always existed, the power shift escalated tensions into an open strategic rivalry. The border incursions in the Western Sector in 2013, 2014, the Doklam standoff in 2017, and the Galwan hostilities in 2020 fundamentally altered the nature of bilateral relations. As forces from both sides remained locked in a tense standoff along the border, the impasse persisted for four and a half years. It was finally resolved through an agreement on a “patrolling arrangement,” announced on October 21, 2024, paving the way for a meeting between Prime Minister Modi and President Xi Jinping in Kazan.

A positive development following the Galwan clash was that both sides kept communication channels open. The gradual thaw in relations can be attributed to 21 rounds of talks at the corps commander level, 17 rounds of meetings under the Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination (WMCC), and multiple discussions between the foreign ministers and national security advisors of India and China.

BREAKING THE ICE AND RESET

Since the Modi-Xi meeting in October 2024, India and China have intensified high-level engagements. Their defence ministers met in Laos in November during the 11th ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting-Plus. This was followed by the 32nd WMCC meeting and the 23rd Special Representatives’ Meeting in December, held in New Delhi and Beijing, respectively. In January, the Foreign Secretary-Vice Foreign Minister Mechanism convened in Beijing, and in February, their foreign ministers met in Johannesburg. The 33rd WMCC meeting was subsequently held in Beijing in March.

The flurry of exchanges indicated that both sides had learned valuable lessons from the prolonged standoff. The continued deployment of troops posed a significant burden on both countries—not just militarily but also by hindering political, diplomatic, cultural, and trade engagements. In India, political and business circles expressed concerns over restrictions on visas and direct investment from China. Given the external and domestic uncertainties in both nations, fostering closer people-to-people and economic ties while simultaneously addressing structural issues would be in the best interest of both populations.

FUTURE OUTLOOK

There is a great deal of negativity about each other in both countries—China tends to look down on India, while India does not think big of China. Both perspectives are problematic. As emphasized by the Indian leadership, fostering mutual trust, respect, and sensitivity toward each other’s concerns is essential.

While there is a considerable gap between India’s comprehensive national power and China’s, India is far from a small country. It is a vast market driven by massive domestic consumption, while China has built immense manufacturing capacities. China could play a role in India’s Make in India initiative, as relying solely on trade surpluses with India and the rest of the world may not serve China’s long-term interests—sooner or later, calls to de-risk and decouple will grow louder, albeit difficult to realise in short term.

India offers significant opportunities for development across primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors, and China’s development experience including alleviating millions from the poverty could serve as an excellent case study for India’s development. But would China invest in building capacities in India the way the West did in China? Many in China remain sceptical, but not everything needs to be viewed solely through a security lens.

Relaxing the rigid visa regime and allowing freer movement of people, goods, and technology, as seen in their civilizational past, would benefit both nations. The tourism and hospitality sectors, in particular, would thrive with air connectivity, and joint efforts should be made to develop Buddhist corridors. Similarly, academic and institutional exchanges must be strengthened. If India is initially hesitant, China could take the lead by following its unilateral globalization approach.

Prime Minister Modi’s call for India and China to “compete in a healthy and natural way” reflects a pragmatic recognition of their shared interests as well as their inevitable rivalry. Given the current state of India-China relations and their roles in the global economic and political architecture, both must ensure that differences do not escalate into disputes or conflicts. Moreover, as Western narratives face headwinds, China and India—two of the largest and most influential developing countries—have a unique opportunity to jointly shape the future of the Global South.

* B.R. Deepak is Professor, Center of Chinese and Southeast Asian Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.