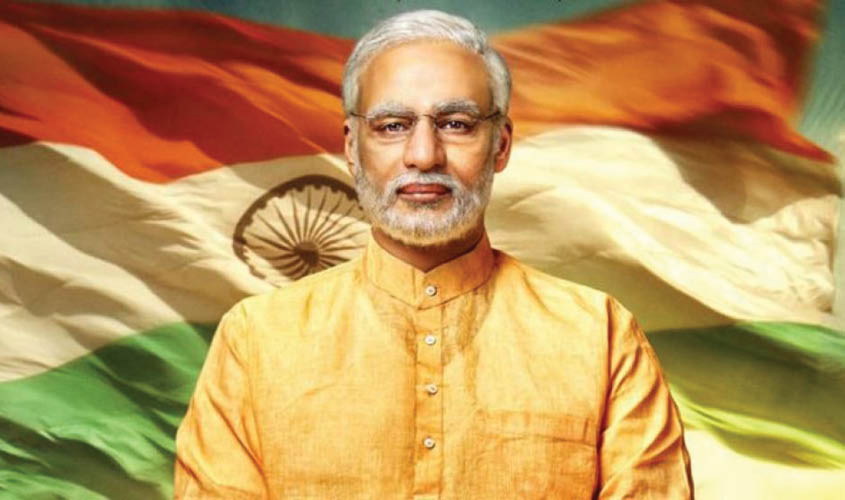

Biopic on Modi has been banned by CEC until 2019 Lok Sabha elections get over.

The present Election Commission of India (ECI) , had it been around in the 1980s, may have stopped the screening of Attenborough’s Gandhi on the grounds that exhibiting the movie gave an electoral advantage to the party in which the Mahatma served for much of his life. Similarly, it may have advised US authorities to block the screening of Spielberg’s Lincoln during the period when a Presidential election was taking place, so that Lincoln’s Republican Party did not derive (what in the Commission’s view would be) an unmerited advantage caused by such a screening. The Chief Election Commissioner and his colleagues have banned Vivek Oberoi’s biopic on Narendra Modi from being screened until the lengthy 6-week period deemed necessary by the Election Commission for conducting the 2019 Lok Sabha elections gets over. Producer Vivek Oberoi ought to sue the EC for punitive damages, as the ban means that the very period when overflow audiences may be expected for the movie will end without it having been screened. The propensity of colonial-minded institutions and officials in India to pass order upon order that restricts the lifestyle, liberty and property of India’s 1.27 billion non-official citizens has only multiplied over the years rather than get scaled back, as ought to have been the case. In an order that has a scope apparently going beyond even the renowned Pyongyang Model of Free Speech, the ECI has ordained that any “material that subserves the purposes of any political entity or individual connected to it” needs to be blocked until examined by a committee headed by a retired Supreme Court judge or a former Chief Justice of a High Court. Given the pace at which the machinery of justice functions in India, it is a near certainty that a verdict on such a stoppage of free expression is unlikely to come before an election (or the next) get over. Should the committee finally rule against such orders, the EC could go on appeal to the higher courts, so that serving judges get the opportunity to deliberate and decide on the decisions of retired brethren. To those unschooled in the arcane mindset so beloved of officials steeped in the colonial processes lovingly retained by that admirer of officialdom, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, it seems odd to expect that political parties, candidates and their supporters would seek not to do what the Election Commission regards as anathema, which is to be in support of actions that have the effect of “furthering electoral gains” and “advancing the electoral prospects of a candidate or party”. Without specifying what it means, the Election Commission of India, which has been hand-picked by the Modi government, seeks to enforce a “level playing field” amongst all candidates and parties. Would the ECI clarify in operational terms what this vague phrase means? Will it start by enforcing the limits on expenses mandated by law, and disqualifying those candidates who exceed even by a rupee the unrealistically low election expenditure limits set by law.

Is a citizen of India so simple-minded that he or she would change voting behaviour simply by watching a movie, even assuming that such a change is not the fundamental right of every citizen? Is it not the right of every citizen to watch whatever movie he or she wishes, provided that it does not deal with noxious themes such as child pornography? Congress President Rahul Gandhi has refreshingly spoken several times about doing away with colonial-era laws such as those relating to criminal defamation, laws whose existence he was clearly unaware of during the ten years before his party lost the 2014 Lok Sabha polls. Rather than seek to block a clearly adulatory movie about Modi, what admirers of the Nehru family should have done was to produce a film about Rahul Gandhi, showcasing him as the ideal 21st century leader that India needs. It needs to be added that while several may view either or both the Rahul and Modi biopics, few of them are likely to vote simply on the basis of such a viewing. Only the Election Commission of India believes that our citizens are too simple minded to be trusted with the products of cinematic licence. In the past, thousands of years ago, some in society were judged not deserving enough to be taught to read and write, and were forced to remain illiterate. Ekalavya had his thumb amputated for bettering a so-called “higher born” youth in archery. A similar complex, that most of us in India just do not merit the rights and freedoms enjoyed by citizens of countries such as the US or the UK, seems to be at play within the governance structure in India, where decisions

Fortunately, the Supreme Court of India seems to be listening to the need for transparency. The absurd proposition by a law officer that documents should be treated as non-existent because they were photocopied and published in a newspaper was just dismissed by the SC. A Law officer has now argued before the Apex Court that the ordinary citizen has no right to know just who is donating vast amounts of money to political parties, when almost nobody gives such a payment unless he or she is paying for past services or is giving an advance on future favours. Surely a citizen needs to know if individuals such Dawood Ibrahim, a sometimes resident of Karachi, are among those who through associates in India have given funds to any political party. Secrecy about sources will only protect the Dawood Ibrahims from discovery. Why should any law-abiding individual be “shy” of admitting that he or she has funded a political party? Surely that is not a crime in a democracy. Fortunately, the SC has dismissed such a colonial-era argument as well although as yet only the ECI and not the citizenry is to be given information on donors. Given that the colonial mindset of so many officials prevent them from regarding ordinary citizens of India as deserving of freedoms and rights denied them through a maze of laws and regulations based on the British era, hopefully the Supreme Court of India will move further in the direction it is now taking, much as the US Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren did in the 1960s to expand the boundaries of freedom in that country and create the foundations for strong growth. India needs a similar era of judicial activism in defence of rights and freedoms not of the state but of the citizen. Rights and freedoms that are essential for double digit economic takeoff in the era of the Knowledge Economy.