Jinnah’s idea of a distinctly separate holy land for Muslims comprised five provinces including Assam.

What is today the controversial National Register of Citizens had its slow and scattered beginnings at the turn of the 19th century into the 20th. The attraction of Assam was its plentiful land, watered by several rivers, especially the mighty Brahmaputra. A number of rivers became narrow during the dry season, exposing fertile margins that were locally called “char” lands. These were unoccupied and there for the picking by the immigrants who came from East Bengal, where there were too many residents but limited land. As population grew, gradually more migrants came into Assam. As they worked hard and accumulated surpluses, they could buy parcels of normal land from willing sellers. Until about 1937, there were few settlements, by design, of East Bengali immigrants in Assam.

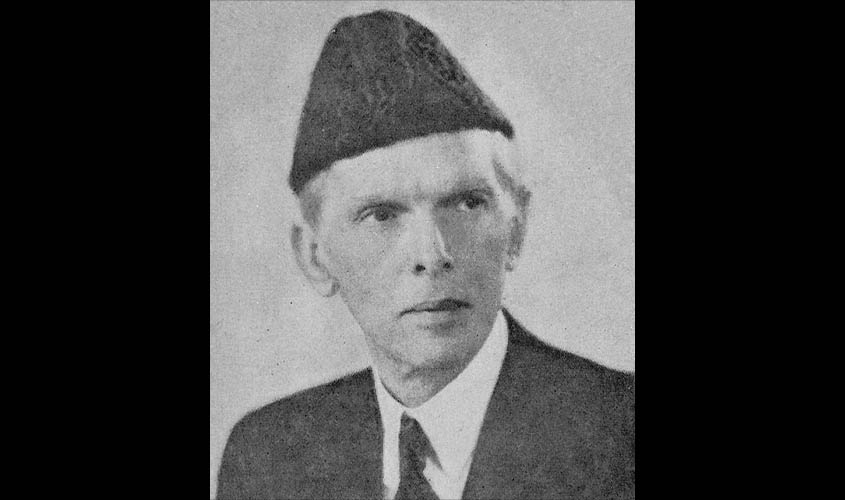

Under the Government of India Act of 1935, provincial governments were formed by political parties. Soon enough, Sir Muhammed Saadulla of the Muslim League became the Premier of Assam. In the 1937 elections, the League led by M.A. Jinnah was disappointed with its meagre victories in UP, the largest province. So the talk of a distinctly separate holy land for Muslims began in all seriousness. The idea was first concretely mooted by the poet Iqbal, who presided over the 1930 League session at Allahabad. A few years later, a Cambridge University scholar, Chaudhry Rehmat Ali worked out a theoretical note and innovated the name Pakistan, the land of the devout. Jinnah’s idea was that five provinces should comprise the holy land, namely, Assam, Bengal, North West Frontier, Punjab and Sind. Balochistan came in later. From the Muslim majority angle, Assam appeared touch-and-go to Jinnah although the Hindu impression was that they had a clear majority. Premier Saadulla got down to the business of facilitating as many East Bengali Muslims to come across and settle in Assam. A parallel whisper campaign was started that the Adivasis were not really Hindus but worshipped animals or were Christian. There was thus a race to somehow prove that there were more Muslims in Assam than Hindus.

In the course of a discussion in Shillong in 1945, Viceroy Lord Wavell noted in his diary that while the reason for the encouragement of this migration was officially justified as being to grow more food, the real objective was to increase the number of “Mohammadans” (as recorded by B.K. Nehru in his book Nice Guys Finish Second).

The tale of illegal migration into Assam is an old one, told by all observers but swept under the carpet by the Congress party and its Muslim supporters, and other distinguished Muslims like Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the late Pakistan Prime Minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who openly expressed the view that without Assam the economy of East Pakistan could not be complete.

The census report of 1931 had recorded a rise of Muslim population due to migration from East Bengal generally and Mymensingh in particular. Nevertheless, Muslims comprised under 27% of the population of Assam. The 1941 census report showed that this figure had gone up to nearly 34%. Immigration of East Bengali colonists was pouring in, was a remark recorded by the Census Superintendent of Assam, C.S. Mullan, ICS. Incidentally, by 1921, the cultivators from East Bengal had gone much beyond the southern districts of Assam and into the central areas.

The situation has been heart rending for those who care for Assam. This writer has often visited the state and seen all its tea growing sub-districts. I was there for some ten days during the 1983 elections, which were boycotted by those who loved Assam. In many of the Assembly constituencies, the voting was pathetically low although the Hiteswar Saikia government had ensured perfect law and order. Most of the booths in the heartland constituencies were manned by electoral officers flown in from other states. Yet, in one constituency, only 268 votes were cast, and in many, not more than a few hundred or thousand people voted. The candidates were too frightened to campaign. Except for the then Bengali speaking Cachar and Goalpara districts and possibly Barpeta, there was a total bandh. I spent those five days based in Guwahati and could not buy even a bidi or cigarette. I only saw birds and occasionally a rushing caravan of six to seven Ambassador cars, filled with government officers. I could move about in my hired car only because of the boldly printed labels of “Press” and with a friend who posed as a photographer. The reported massacre in Nellie took place on the morrow of the voting day.

Quoting from the Hindustan Standard, at the time a well patronised Kolkata daily, Dr Rajendra Prasad, in his book India Divided (published 1946), had stated, “It is sad but by no means improbable that in another 30 years Sibsagar district will be the only part of Assam in which an Assamese will find himself at home.”

The Census Report of 1941 completes the story with a short but significant sentence: “The most noticeable rise in the Muslim population is in Assam and once again represents migration from Mymensingh and east Bengal generally.” This policy of colonisation of Assam by the Muslims of Bengal was continued under the joint auspices of the Muslim League ministries of Sir Saadullah in Assam and Sir Nazimuddin in Bengal, as the following Bengal Government communiqué published in the press, in the last week of October 1944, where it goes on to quote the census report of 1941, shows: “The Government of Assam in their resolution dated the 21st June 1940 prohibited settlement of land with persons coming from outside the province after the 1st January, 1938. The Bengal Legislative Council went on to appeal to the Governor to ask for the Viceroy’s intervention in Assam.”

Dr Prasad quoted a retired S.P. Desai ICS, writing in Hindustan Standard of December 1944: “Every day new bamboo sheds and temporary huts are springing up in the reserves. I found that the immigrants absolutely ignore the local officers. The few Nepali graziers and Assamese Pamuas finding no protection from anywhere give ‘dohai’ in the name of the King-Emperor. Verily the cup of humiliation for the Assamese was full.”

The Indira Gandhi government, in collaboration with the Assam Chief Minister Hiteswar Saikia suppressed the people of Assam and their sentiments. They continued to protest and agitate but to no avail. As if to rub salt in their wounds, the Central government passed the pernicious Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunals) Act in 1983. Hereby, in Assam the onus of proving that a particular person is an infiltrator rested with the complainant or the government of Assam, and not on the suspect. The Foreigners Act of 1946, whereby the onus of proving his bona fides is on the suspect, continued to apply to all other states in India. The only exception made was Assam to help the illegal migrants.

When travelling from Guwahati to Shillong, one does not spontaneously realize when one has crossed from Assam to Meghalaya. Yet in the latter state, the Central law was the old 1946 Act. Such was the discrimination against the Assamese people.

Soon after becoming Prime Minister in 1985, Rajiv Gandhi ceased to ignore the lamentations of the people of Assam and initiated negotiations, especially with the youth. After much talk, give and take by the stakeholders, an accord was signed. One of its most important clauses was the compiling of a National Register of Citizens. The intention was probably national and not to confine the compilation to Assam although this state was the priority. But it was not commenced for the following 30 years until the present ministry at Dispur began the exercise. Incidentally, nothing was done to withdraw the IMDT Act until the Supreme Court struck it down as ultra vires in 2005.