A swarm of AI-powered drones or unmanned tanks could manoeuvre and strike in fractions of a second, outpacing any human commander’s ability to respond. But the same speed that promises advantage on the battlefield also raises the spectre of uncontrollable escalation.

On a screen in a military command centre, an AI algorithm flags a target. Within seconds, a drone locks on and fires—no human pressed the trigger. This scenario is no longer science fiction. In recent conflicts, we have seen glimpses of these autonomous weapons systems (AWS) in action. Israel, for example, reportedly deployed AI tools code-named “Lavender” and “Where’s Daddy?” to identify suspected militants and track them to their homes for targeting. An algorithm called “The Gospel” sifted through surveillance data to generate lists of buildings for airstrikes. Meanwhile, a U.S. defence startup, Anduril Industries, is developing software to coordinate swarms of thousands of autonomous drones for the Pentagon. Major leaders in AI products such as Alphabet and OpenAI are also entering the realm of defence.

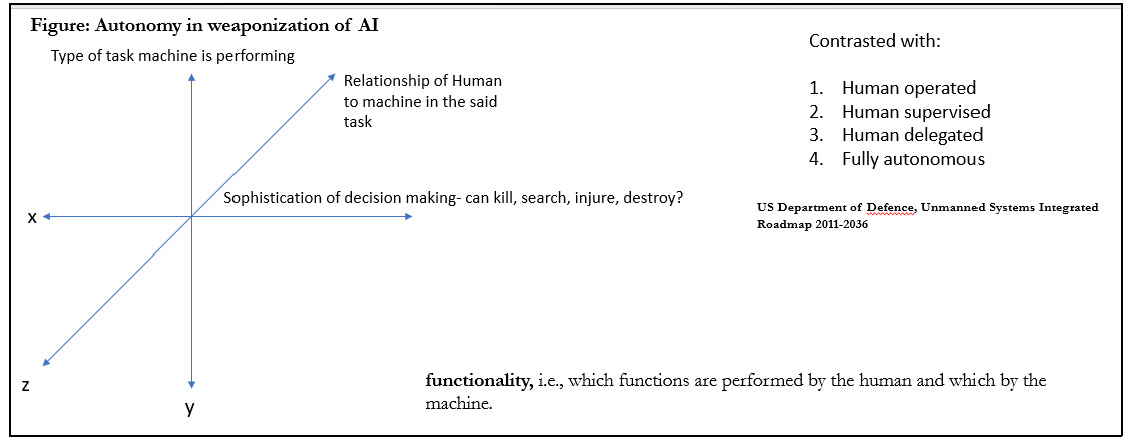

AWS differ fundamentally from previous advancement in weaponry. Nuclear, chemical, and biological arms magnify a human’s capacity to kill, but a human is still in charge of when and where to unleash them. By contrast, AWS shift life-and-death decision-making from man to machine. In plain terms, these are weapons that, once activated, identify and attack targets on their own. An autonomous weapon might decide who lives or dies based on sensor inputs and code—not conscious human judgment. This handover of lethal decision authority represents a profound change in warfare. It’s a change that the world, and India in particular, cannot afford to ignore. We urgently need international rules for this new class of weaponry, because allowing machines to make kill decisions without robust oversight is a recipe for disaster.

Strategists warn that AWS could upend global military dynamics by making conflicts faster, less predictable, and harder to control. Proponents of autonomous weapons talk up their advantages: freed from human limitations, machines can process information and react at lightning speed. U.S. military planners, for instance, believe AWS will be “far faster and more agile” than manned systems, capable of undertaking “thousands of complex and highly coordinated decisions at machine speeds.” A swarm of AI-powered drones or unmanned tanks could manoeuvre and strike in fractions of a second, outpacing any human commander’s ability to respond. This might tempt nations to entrust more and more combat roles to algorithms in hopes of gaining a split-second edge over adversaries.

But the same speed that promises advantage on the battlefield also raises the spectre of uncontrollable escalation. Human leaders could simply be too slow to keep up. As one analysis cautions, if military action starts to occur at “speeds driven by machines,” political leaders may “lose the ability to manage the crisis and with it the ability to control escalation.” Imagine rival AI-guided missile defence systems or drone swarms interacting in unexpected ways—a misinterpreted move could trigger a cascade of attacks before any human can intervene. In the world of high-frequency finance, we’ve seen algorithms cause flash crashes. In warfare, a similar “flash war” could be catastrophic. Autonomous weapons can “accelerate the use of force beyond human control,” risking conflict spiralling in “unpredictable manner”. Crucially for India, which borders two nuclear-armed nations, such loss of control is a nightmare scenario. In a confrontation between states with nuclear capabilities, the fear of “losing at machine speed” might prompt one side to escalate to the nuclear level out of panic. AWS could thus lower the threshold for conflict and even erode the deterrent balance that has kept nuclear peace for decades.

India, as an emerging power in a volatile neighbourhood, must pay close attention to these strategic shifts. China is sprinting ahead in AI-driven military technology, investing heavily in autonomous drones, surveillance, and decision-support systems. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) openly anticipates that AI will “fundamentally change the character of warfare,” and is determined not to fall behind in this military-technological race

Beyond the strategic risks, AWS pose stark ethical and legal questions. Warfare has always been tragic, but at least humans could be held responsible for their decisions in battle. Who do we hold accountable when a machine decides to pull the trigger? When an autonomous drone misidentifies a civilian as a combatant and opens fire, is the blame on the commander who deployed it, the programmer who coded it, the company that built it, or the machine itself? The fog of war could become a fog of liability. It is telling that the International Committee of the Red Cross and many legal experts insist that humans must retain responsibility for the use of force, precisely because machines cannot be held accountable under international humanitarian law. A robot has no concept of justice or mercy, and you cannot put an algorithm on trial for war crimes.

By delegating kill decisions to AI, we also risk stripping war of basic humanity. However brutal a conflict, there is (or should be) a conscious moral agent deliberating on proportionality and trying to minimize unnecessary suffering. As the UN Secretary-General António Guterres remarked, weapons that can target and attack humans on their own are “morally repugnant and politically unacceptable.” Even if an AI could be programmed to never technically violate the Geneva Conventions, it could never understand the why behind the rules. As one delegate at the United Nations starkly put it, “an algorithm must not be in full control of decisions that involve killing or harming humans.”

Legally, the introduction of AWS muddies the waters of international law. The laws of armed conflict demand distinction between combatants and civilians and proportionality in any attack. Can a synthetic mind reliably uphold these principles in the chaos of battle? If an autonomous weapon’s actions lead to an illegal massacre, how would we apply existing law? These unanswered questions make AWS a dangerous legal grey zone. The world faced similar challenges with previous new weapons (like chemical gases or nukes) and responded by forging new treaties. For autonomous weapons, a clear legal framework is urgently needed before they proliferate further.

Diplomats have begun discussing AWS in forums like the UN Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) for several years, but progress has been painfully slow. Thus far, we’ve seen vague guiding principles, voluntary pledges about “human control,” and talk of a possible future agreement. It resembles the early days of nuclear arms control, when hope lingered that informal understandings might suffice, only to be crushed by a full-blown arms race. With AWS, the pace of technological advancement is blistering. Laboratories and defence startups won’t wait for UN working groups to catch up. Every year of dithering increases the odds that autonomous killing machines become entrenched in military arsenals around the world. Once that happens, reining them in will be exponentially harder.

What might effective regulation look like? History provides some guidance. To prevent nuclear proliferation, the world established the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which monitors nuclear programs, conducts inspections, and enforces safeguards. For chemical weapons, we have the OPCW performing a similar role. We need a comparable global body for autonomous weapons—a dedicated agency to ensure transparency, accountability, and oversight of military AI. An “International Autonomous Weapons Agency” could mandate that countries report on any AWS they develop, subject those systems to review, and certify which abide by agreed rules (for example, a rule that meaningful human control is required over any use of lethal force). It could investigate violations, such as incidents where an AWS caused unlawful harm, and recommend sanctions or remedies. Crucially, it would serve as a forum where nations can assess each other’s actions, building confidence that no one is secretly launching Skynet behind everyone’s back.

Sceptics will argue that AI is intangible and harder to monitor than uranium stockpiles—and they have a point. But while the technical challenges differ, the principle of trust but verify remains applicable. International oversight can shine light on developments that, if kept secret, would spark paranoia and arms build-ups. Clear rules, backed by inspections and audits of critical systems, can create barriers to reckless deployment. For instance, states might agree not to automate the “kill web” beyond a certain point, and an AWS agency could verify compliance by testing weapons or reviewing their programming under mutual agreement. These are complex tasks, but not impossible if there is collective political will.

India, with its growing technological prowess and status as a responsible nuclear power, is well placed to champion this initiative. We have experience balancing cutting-edge development with global norms—our space and nuclear programs, for example, have by and large been pursued cautiously to avoid triggering instability. Moreover, India has long advocated for disarmament and arms control in international forums. Taking the lead on AWS regulation would be in line with our tradition of promoting peace and responsible science. It would also ensure that any new rules account for the security concerns of developing and non-Western states, not just the agendas of major powers. By proposing an IAEA-like framework for AI-enabled weapons, India can assert moral leadership on the global stage. Such leadership is not just abstract virtue; it directly serves our national security. In a world of agreed limits and inspections, India would not have to worry about an opaque Chinese autonomous arsenal—there would be mechanisms to keep tabs on it. The alternative is a wild west of autonomous arms, which would be far worse for a state with as many potential threats as India. Indian policymakers have a narrow but crucial opportunity

* Pooja Arora is a PhD candidate at Jawaharlal Nehru University.