Scores of inheritors in sports, cinema and corporate India have failed despite having all the initial advantages. The natural question is why doesn’t the same happen in politics?

Thousands of articles, columns, podcasts, debates and television shows have already peppered politically inclined Indians in the aftermath of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections. Barring a few honourable exceptions, the post-mortem has been anchored by ideological affiliations and prejudices. In this age of polarised partisanship where confirmation bias has become the norm, that is hardly surprising. Accusing a journalist of being partisan is meaningless; it is like accusing a municipal corporation employee in Delhi, Rajkot, Bangalore or Mumbai of being corrupt. The glaring example of this can be seen in how the post-mortems have treated the “unexpected” performance of the Congress. The “Godi” media has called the near doubling of the Congress Lok Sabha seat tally as a flash in the pan and is going on and on about how Rahul Gandhi hoodwinked voters with the Rs 100,000 per year false promise. The “Pidi” media is busy singing paens to the rise of yet another Gandhi who is destined to rule India. They are convinced Priyanka Gandhi Vadra would have defeated Narendra Modi in Varanasi. The very few who remain independent applaud the success of the Congress as a strong opposition as tonic for a healthy democracy, but also point out that the Congress cannot rest on its laurels as the serious task of rebuilding the party organisation in important states remains unfulfilled.

If you are a non-partisan observer of Indian politics and have followed the results of the Lok Sabha elections closely, another trend is very clearly discernible. And it deserves more attention and analysis from political scientists. It is the enduring success of political dynasties in the country. For years, if not decades, we have heard everyone say how political dynasties are cripplingly injurious to a democracy. We have heard how dynasties have built such formidable barriers to entry that talented and better equipped leaders cannot break through the obstacles. We have heard how this conscious promotion of the dynasty culture encourages even more corruption and nepotism. After all, if tons and tons of money were not to be made, why would sons, daughters and assorted relatives choose only electoral politics over so many other promising careers? In scores of other genuine democracies, you will not find sons and daughters “inheriting” political parties the way Mukesh & Anil Ambani inherited the Reliance corporate empire from their father, the legendary Dhirubhai Ambani. The three-time Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been railing against “Pariwarwad” or dynasty politics for more than a decade. BJP leaders keep chanting ad nauseam the mantra of rooting out dynasty politics. And yet, what have the election results revealed?

The mysterious and troubling fact is: while brazenly dynastic parties have done quite well, political parties without sons, daughters, nephews and nieces ready to “inherit” or already inherited the “throne” are seen to be struggling for political relevance and survival. There are exceptions, of course. And caveats always apply. But that is the stark reality of contemporary Indian politics. Many commentators have highlighted this aspect of Indian democracy since long. Quite a few have called this a blot on Indian democracy. The authors want to once highlight this trend and hope there is a serious debate in India over this phenomenon and if there is any way for merit to score over inheritance in Indian democracy. The fact is: dynasties are present in almost every sphere. Cricket, Bollywood, India Inc, Law (talk to senior lawyers and you will be shocked by the levels of dynastic “lordship” in the profession) and more. Yet, in most other fields or professions, being an entitled dynast ally allows you the privilege of “entry”. After that, your future as an inheritor depends on your merit and how the public judges you. Scores of inheritors in sports, cinema and corporate India have failed despite having all the initial advantages. The natural question is why doesn’t the same happen in politics?

Let’s look at the Lok Sabha elections. The Shiromani Akali Dal has been going through troubled times for a while. Since the 1990s, the late patriarch Prakash Singh Badal “converted” the identity based Panthic party to a dynasty-controlled outfit. His son Sukhbir Singh Badal and daughter-in-law Harsimrat Kaur Badal have effectively “inherited” SAD. They were wiped out by the AAP wave in the 2022 Punjab Assembly elections. Nobody gave the Badals a hope in hell in the 2024 elections. They lost all the seats SAD contested in. Except one called Bhatinda. Harsimrat Kaur Badal has been winning this Lok Sabha seat since 2009 and she defied all odds to win again in 2024. In nearby Haryana, the Lal dynasties have fragmented in fratricidal warfare. But a new dynasty has cropped up. Locals in the state are convinced Bhupinder Singh Hooda will be back as Chief Minister after Assembly elections due in October and that his Lok Sabha MP son, Deepender Hooda is the future CM. In nearby Rajasthan, former Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot has been trying for almost two decades to marginalise and sideline Sachin Pilot, son of the late Rajesh Pilot who was a friend of Rajiv Gandhi. Yet, Sachin Pilot retains the family charisma and influence.

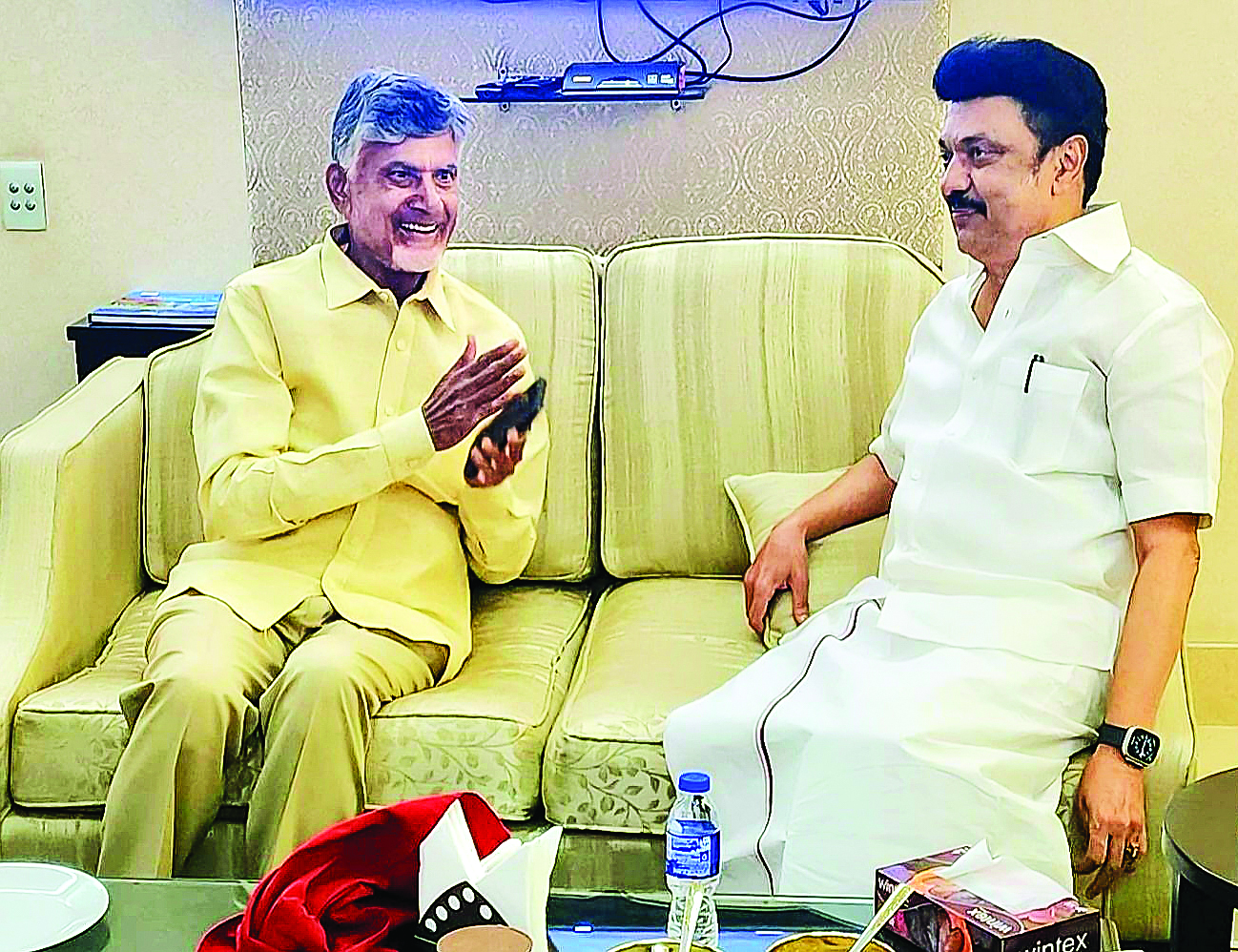

Thousands of kilometres down South, the dynasty of the late M. Karunanidhi rules supreme. Inheritor M.K. Stalin is the Chief Minister. His son Udhayanidhi Stalin is waiting in the wings to be the CM. Daughter Kanimozhi is a Lok Sabha MP. Cousin Dayanidhi Maran is an MP. In Andhra Pradesh, a “dynast” N. Chandrababu Naidu (son-in-law of the late NTR) defeated yet another dynast Jagan Mohan Reddy. It is only in Telangana that the dynastic party BRS of former CM K.C. Rao that crumbled. In Maharashtra, voters seem to have indicated the Uddhav Thackeray is the real inheritor of his father Balasaheb’s legacy than Eknath Shinde. In the internal family war of the Pawars, voters chose the daughter of Sharad Pawar, Supriya Sule over Sunetra Pawar, the wife of nephew Ajit Pawar. In Bihar, inheritor Tejashwi Yadav has shown he is a long-term player; as has the other inheritor Akhilesh Yadav in Uttar Pradesh. In West Bengal, the anointed inheritor Abhishek Banerjee, nephew of Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee is reigning supreme.

In contrast, parties without “inheritors” are floundering. The AGP once ruled Assam. It is now a fringe ally of the BJP. The AIADMK is disintegrating as there was no “inheritor” when Jayalalithaa died in 2017. The BSP is withering away as Mayawati hesitated too long to designate an inheritor. And the BJD in Odisha is at a crossroads since Naveen Patnaik has no inheritor.

What does all this say about the quality of Indian democracy?

Yashwant Deshmukh is Founder & Editor in Chief of CVoter Foundation and Sutanu Guru is Executive Director.