In our post-Enlightenment world, where scientific endeavour, logic and reason are part of the triptych that propels economies and development, it is almost every quarter of a year that a new technology surfaces and gives direction to humankind. Among many such developments the advent of 3D-printing technology stands out as an engineering landmark, which has already brought about a radical shift in the way we think about manufacturing. A 3D printer is the miniature equivalent of a whole industrial production chain. This means that it›s now possible “print out” complexly designed objects at the touch of a button — from tiny artefacts to, at least in theory, full-scale industrial-grade items, like, say, the fuselage of an aircraft.

Though 3D printers might seem as a marvel of the present, the technology was first conceived back in 1980, when Dr. Kodama in Japan filled an incomplete form for patenting what was then termed as Rapid Prototyping (RP) Technology. The goal at first was industrial production, and surely no one could’ve known where the technology was headed at the time.

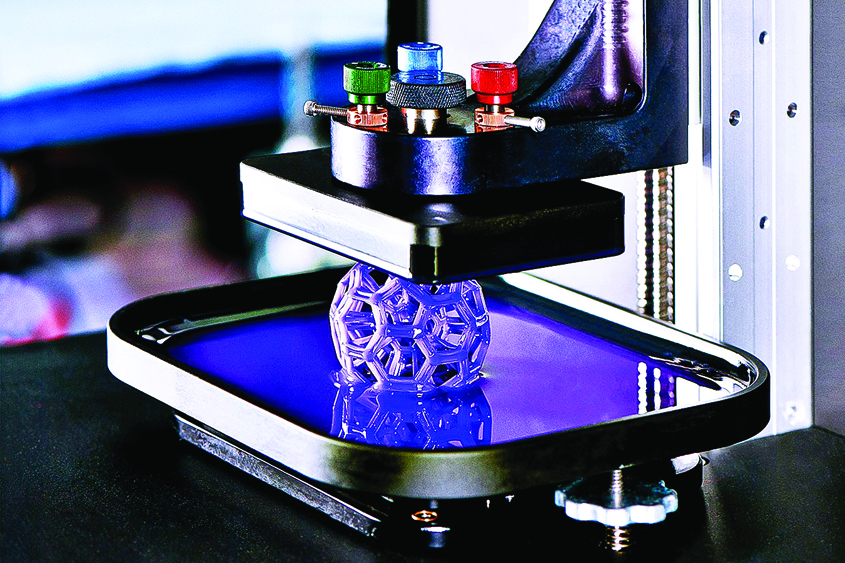

Today, 3D printing, as per industry jargon, is referred to as Additive Manufacturing (AM) technology. The latter term explains the process with the utmost clarity: the physical object takes form as the printer prints one layer over another progressively, and quite meticulously at that, until the complete three-dimensional object is obtained, thus the term ‘additive’. This process might sound simple, which is the way to go with all brilliant ideas in production, but it is this very process that leads to the creation of some of the most complex looking three-dimensional designs.

this leaves us with the obvious follow-up question: what exactly can it make? In India, at this very point, the largest producers in Rapid Prototyping technology and Rapid Manufacturing, according to statistical data and number of clients, is Imaginarium. They are based in Mumbai and have been in operation since 2009. In a conversation with Guardian 20, Tanmay Shah, Head of Innovations at Imaginarium, enumerates the areas that 3D printing has impacted since its arrival in India. “3D printing,”he says, “is used for prototyping in a large number of industries, such as automation, FMCG, aviation, and white goods along with production in jewellery and accessories and medical aid.” He goes on to exclaim, “It’s amazing how quickly it can turn around a concept into a physical product, with virtually limitless design freedom.”

Imaginarium has a vivid history that began with the discovery of 3D-printing technology’s capacity for jewellery production, made by the founders Kamlesh Parekh and Dipak Shah in 1995. They brought the technology to India in 2003 and it was gradually that it gained pace along with the global strides being made in 3D-printing technology’s development. The numerous ways in which this technology can contribute to industrial prototyping is easy for one to imagine. You can think of various tools and intricate parts of machinery which can now be easily printed. But how does 3D printing help in the medical field and in jewellery-making? Shah quickly responds, “At Imaginarium we’ve bifurcated our production capabilities. We have what we call as Imaginarium Precious, a limb under which we actually produce beautiful, intricate jewellery as well as moulds that are used for jewelry making.” He adds, “And, under the Imaginarium Life label, we arm the medical fraternity with tools that improve upon the traditional procedures by 3D printing implants, anatomical models that mimic real-time cases and even customised prostheses.”

Like our standard printers require ink for printing on paper and other surfaces, a 3D printer uses raw material for producing a three-dimensional object. Some of these include plastic, nylon, a variety of photo-reactive resins, paper, glass and metal. Shah actually adds two more to the list, which makes it all the more baffling. He says, “You can even use food! We even print using chocolate for some of our customers.” He continues, “Recent advancements in the field have given rise to a whole new domain, that of 3D bio-printing, where 3D printers have been utilised to print living tissue and completely functional organs!” Maybe we are not too far from turning Mary Wollstonecraft’s fictional monster from Frankenstein into a stomping and heaving reality.

Another interesting point is to observe the slight time lag that the Indian market showed in bringing this fascinating technology to the people. Indians, over various mass media portals, had already received and even viewed the 3D printing mania that was prevalent in Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States of America a good half a year before it made its presence felt in India in the early months of 2017. Thus, this makes evident the slow absorption in India of new technologies. To this Shah has a reply, “Take the case of any disruptive technology and you’ll find a similar trend when it comes to India to the introduction and adoption of that technology.” He continues with the possible reason for this behavior, “That’s because we are inherently apprehensive about testing new waters and rely on the innovations and applications from around the globe to mark a technology ‘safe’ for adoption.” On a brighter note he adds, “But once our market accepts a new technology, we don’t look back.” It is important to note here that India is still at a stage where we are importing the technology from the USA, China and Europe.

A company named 3D Hubs, which was started in Amsterdam, today provides a website called 3dhubs.com, which can instantly locate the nearest local 3D printer to you. It can in fact help you with selecting the material out of which you want your desired object to be made, along with uploading the design you intend for it to have. This helps you to reach out to many such 3D printers in India, but where Imaginarium takes a special place is with its unique programmes in jewellery development, as well as with its “Metamorphosis Limb” wherein they aim to bring the technology directly in contact with the consumer, thus allowing you to not only get something made for yourself but also to have a look at how it is being printed. Shah makes a very convincing remark when he says, “Bringing 3D-printing technology to people today is like introducing a computer at a school or a college, there is curiosity and doubt, but you know that it will blow them away in the future.”

As far as the consumerist experience goes, buying a 3D printing product is the ultimate step one can take at customisation and personalising a product for themselves in a market where identical mass produced goods abound. You get to choose your design right from scratch, along with choosing the material it is to be made out of. The CAD (Computer Aided Design) file which has a three-dimensional image of the design is put through a slicing software that slices the whole design into several horizontal sections, thus making the layer-by-layer printing possible, before the 3D printer is given the command to print. The whole process is rather engaging to observe.

When it comes to costs and prices, Shah says, “Cost is a factor of multiple variables, such as design complexity, dimensions, volume, material and, of course, the technology. A simple, customised cover for your iPhone in nylon plastic can cost you anywhere from Rs 1,000-1,500.”

What remains then is the future. “In India, 3D printing is gaining momentum and getting in tune with the government of India’s vision for Make in India,” Shah says. “It has the potential to bring manufacturing into people’s homes. Opening up our knowledge base is key to expanding and taking this technology across the country.”

Maneesh Varshney is the co-founder of DesignOCare, a 3D printing startup in Delhi that started operations one year ago. He has been part of the industry for over two years and has an office set up in Scotland, which is led by the co-founder KanikaBansal.

“I had already been working with this technology for a few years before I made plans for India,” Mameesh says. “And, I observed that theawareness of the technology was much more abroad than here.”

He has a team of three people with seven 3D printers set up at the moment. They not only provide Rapid Prototyping services but also retail 3D printers that are imported from China. “You could get an affordable good quality printer for Rs 25,000 and the prices can go all the way up to Rs 2 crore. But then, those are industrial printers that are able to do large-scale work as well,” he adds.

Another major enterprise is run by Prudhvi Reddy, the co-founder of Think3D, a 3D printing solutions company that has clients like Whirlpool and Tech Mahindra. Referring to a development that he has been able to track, he says, “The Rapid Replication Initiative was an effort that came to the front in the West during 2007, its aim was to make 3D printing and 3D printers easily available to people—this included being able to replicate or rather 3D print the printers themselves. And in 2010 when the costs of production and the printers went down, the movement gathered momentum.”

Reddy started the company three years back and has several clients from large industrial companies to doctors who use the technology for improving their processes. He narrates the stories of some clients that were simply individual consumers looking for something customised: “I recall this customer who came to print the model of a ship from a certain era because the model was not available anywhere else. We’ve had architecture students and even school students who wanted to make models for their projects.”

Think3D guides the client through the whole process — from designing to providing the finished product. Reddy shares that the price range of the products is as wide as Rs 150 to Rs 10 lakh. He says, “We have no minimum or maximum.” Think3D is set up in nine different locations in the country and also conducts seminars for people interested in the industry, for which people can register on their website. Besides, they retail 3D printers in the prince range of Rs 35,000 and 1 lakh.

But there are also some downsides that Reddy has experienced: “The trouble is with the way people have been exposed to the technology, with examples of organs being printed, it makes them expect too much and sometimes there is a mismatch between reality and their expectations. They must realise that the developments are yet to be brought forward for people to use.”

On a more optimistic note, he adds, “Today the young generation using the internet has developed marvelous applications for this technology. We are printing prototypes of new products for innovators regularly. Given that 3D printing can help you do away with investments related to the assembly line of production, we have many new applications and methods in fabrication that we are yet to determine. So, the more we utilise it, the better it shall be for the future of this technology.”