China’s investments in Serbia recently exceeded three billion euros and Chinese infrastructure loans were in excess of eight billion.

Last weekend, six Chinese Air Force Y-20 transport planes landed at Serbia’s Nikola Tesla International airport in Belgrade, carrying FK-3 surface-to-air missile systems for the Serbian army. Serbia will be the first operator of Chinese missiles in Europe, and the FK-3, widely compared to the American Patriot and the Russian S-300, marks yet another step in Beijing’s attempt to spread its influence in the West.

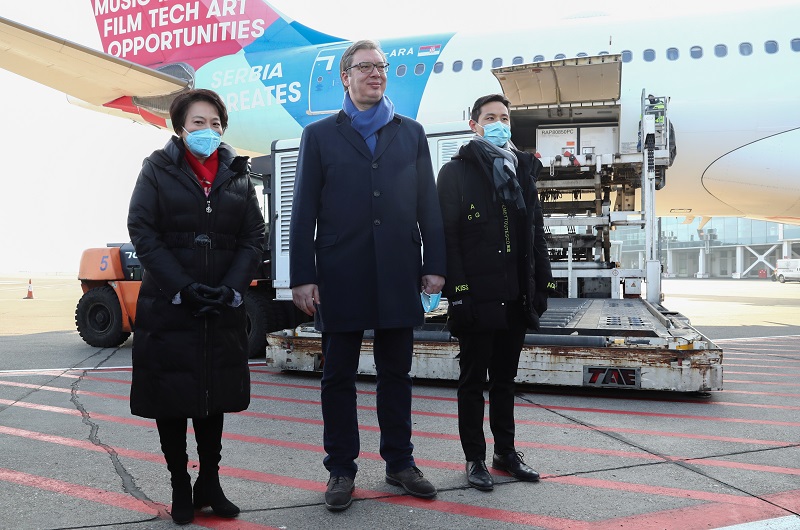

But this was not the first time that Belgrade received assistance from China. Almost to the day two years earlier, Serbia’s President Aleksander Vucic turned up at the same airport to welcome an Airbus from China carrying the largest shipment of aid Serbia received in its effort to combat the coronavirus pandemic. Standing next to the Chinese doctors and shipment of medical devices, Vucic thanked Chinese President Xi Jinping, the Communist Party of China, and the Chinese people: “We should thank them with all our hearts”. Almost overnight, China became the greatest friend of Serbia in the country’s media. A video of Vucic kissing the Chinese flag went viral.

With a population of just under 8 million, Serbia is the largest country in the Western Balkans, a region that has become a Chinese strategic hub that could finally connect the Port of Piraeus in Greece, which China acquired in 2016, with central European countries. In the past, Serbia was a key member of the former Yugoslavia, which Joseph Stalin originally wanted to become a member of the USSR-led bloc of Communist countries. Yugoslavia’s President Tito rejected Stalin’s approach and instead, together with Jawaharlal Nehru, in 1961, became a founder member of the Non-Aligned Movement. Serbia’s historical links with Russia, however, remained resilient, even strengthening after the disintegration of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. A poll last year revealed that 54% of Serbian citizens see Russia as an ally, and 95% viewed it as either an ally or a necessary partner. Only 11% regarded the EU as an ally.

Although Serbia is officially a candidate for EU membership, the country’s strong-man President has shown a half-hearted commitment to the bloc and its values. Instead, his relationship with Brussels has been purely transactional, and as part of this approach, he has built close ties with Moscow and Beijing so that he can extract greater political and economic benefits from the EU by appearing to shift from West to East and back again, whenever it suits him. This strategy appears to be working well, as shown by his landslide victory in Serbia’s general elections two weeks ago. Vucic, a former minister for information in Slobodan Milosevic’s Yugoslav government, won 60% of the vote, although the figure was disputed by the opposition and independent observers. Since his party came to power in 2012, Vucic, a former ultranationalist who earlier served as defence minister and prime minister, has gradually clamped down on mainstream media and institutions assuming complete control of the country.

The question now for Vucic is how long he can keep his geopolitical triangulation going, particularly in the light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Currently, the EU is Serbia’s main source of financial aid, foreign investment and trade, and even prior to the current crisis over Ukraine, Russia could never have replaced Europe as Serbia’s main economic partner. Nevertheless, Serbia is almost entirely dependent on Russian gas for its energy, and its army maintains close ties with Russia’s military. For years, Serbia has taken part in Russo-Belarus-Serbian war games called “Slavic Brotherhood”, cementing the Slavic ties that go back to the Stalin era.

But as the Ukraine war rages on, Belgrade is beginning to feel the heat due to its strong ties with Russia. Although Serbia voted in favour of the UN resolution to condemn Russia for its invasion of Ukraine and supporting Ukraine’s territorial integrity, Belgrade avoided imposing economic sanctions against Moscow. But with Russia facing a long period of political isolation and economic turmoil, Belgrade’s strategy of triangulation looks increasingly unviable and it appears to be only a matter of time before Serbia is forced to pick a side. But President Putin remains popular among the Slavic population in Serbia, so the domestic backlash against any anti-Russian policy would be extremely high, according to Serbian analysts. Despite this, the economic reality is that Vucic has little choice other than to side either with Brussels or, increasingly likely, Beijing.

According to publicly available data, China’s investments in Serbia recently exceeded three billion euros and Chinese infrastructure loans were in excess of eight billion. Last month the “Chamber of Chinese Companies” was opened in Belgrade. During the opening ceremony held in the new Chinese Cultural Centre (built on the site of the former Chinese embassy destroyed by NATO in 1999), Serbian Prime Minister, Ana Brnabic, indicated Belgrade’s preferred direction of travel: “For me, this is an extremely important day for the whole of Serbia, because we live in difficult and complicated times, when many partnerships and ties are being severed, and we are under enormous pressure. The most difficult thing is to preserve partnerships and friendships, but also to strengthen them further and open new corridors of partnership”. For this, read “China is becoming an increasingly attractive partner”.

Over the past few years, many large infrastructure projects in Serbia have been financed by Chinese loans, and all contracts have notably been awarded without public tenders. After a visit by President Xi Jinping to Serbia in 2016, China’s company Hesteel took over a troubled steel mill, previously owned by US Steel. Two years later, China’s Zijin Mining acquired the country’s only copper mining complex, burdened by debt. The main sponsor of Serbia’s top football league, Linlong, just happens to be building a $1 billion tyre factory, and last year the Chinese company Power Construction Company, together with the French firms Alstom and Egis, signed a memorandum with the Serbian government on the construction of the initial two lines of the Belgrade Metro.

China is also increasing its military cooperation with Serbia. In addition to the new FK-3s, two years ago, Serbia’s air force received six combat drones armed with laser guided missiles, the first deployment of Chinese unmanned aerial vehicles in Europe. In the field of security, over a thousand cameras of the Chinese giant Huawei, with facial recognition software, have been installed in Belgrade, creating considerable alarm in the European Parliament, which regards such systems as a threat to human rights.

The new partnership between China and Serbia also includes close political bonds. Belgrade refused to support recent EU resolutions condemning China for crimes against humanity in Xinjiang and its human rights violations in Hong Kong. Also, in exchange for China refusing to recognise the independence of Serbia’s troublesome neighbour, Kosovo (which it claims to be part of its territory), Belgrade supports China’s policy in relation to Taiwan.

Since Vucic took office in 2017, ties with China have strengthened enormously, increasing Beijing’s influence in the region. During the same period, trade with Russia has reached a new low. Add to this the horrifying scenes from Ukraine and tales of rape and plunder by the Russian army, and it’s not difficult to see why Moscow’s influence in Belgrade is reducing.

Also harming Russia’s influence is its increasing inability to invest in Serbia, resulting from the huge damage to the economy caused by its invasion of Ukraine. In a recent video conference with President Putin, the chair of Russia’s Central Bank, Elvira Nabiullina, reportedly told the embattled President that the invasion had “flushed” the Russian economy “into the sewer”. Ratings agency Moody’s said on Friday that Russia might be in default because it tried to service its dollar bonds in roubles. Such an event would mark Russia’s first major default in foreign bonds since the years following the 1917 Bolshevik revolution.

Even worse, many economists believe that Russia’s GDP will suffer a catastrophic drop in the next few years, with permanent medium-to-long term damage. European countries are seeking alternative sources of oil and gas, and plan to bring forward their net-zero carbon emission plans, thereby cutting the need for Moscow’s energy. With lower demand and reduced sales there will be less money in Moscow’s coffers to maintain influence in Serbia, or anywhere else in the world.

In the meantime, China’s predicted GDP growth of 5% in 2022, although low by recent standards, will allow it to continue to invest in Serbia and maintain influence. “I believe in my friend and my brother, Xi Jinping”, said President Vucic in a letter addressed to his counterpart last year. “The only country that can help us is China”. Xi followed up with a response invoking the “iron-clad” friendship between the two countries. With the EU dithering and Russia’s abilities declining, the way is open for China to be Serbia’s key partner and achieve its ambitions in the Western Balkans.

John Dobson is a former British diplomat, who also worked in UK Prime Minister John Major’s office between 1995 and 1998. He is currently Visiting Fellow at the University of Plymouth