Neighbouring countries, such as India, will feel the pressure once again to accept droves of migrants and refugees and reckon with growing lawlessness, violence and desperation along their porous borders with Myanmar.

Murder by the military continues. Local sources in Myanmar claimed last week that the security forces had killed 737 people since the February coup and had rounded up 3,229 citizens across the country. Amid continuing protests, killings and mass arrest, the United Nations has warned that the situation in Myanmar may be heading “towards a full blown conflict”, similar to the civil war gripping Syria in the Middle East. All this on India’s porous northeastern border with Myanmar, stretching almost 1,000 miles.

If the figure of 737 deaths shocks you, “you ain’t seen nothing yet”, in the words of former President Ronald Reagan. In August and September 1988, the last time the country saw such violence when the military put down a pro-democracy uprising, they killed an estimated 3,500 innocent citizens in just six weeks. This time the uprising has been more sophisticated and resilient, but there will be thousands more civilians walking around with invisible targets on their chests, or more likely on their heads. Most of them will be young people, who now form the majority of the protestors. They have witnessed a form of democracy and acquired a taste for freedom since the country’s democratic thaw in 2011; they liked it.

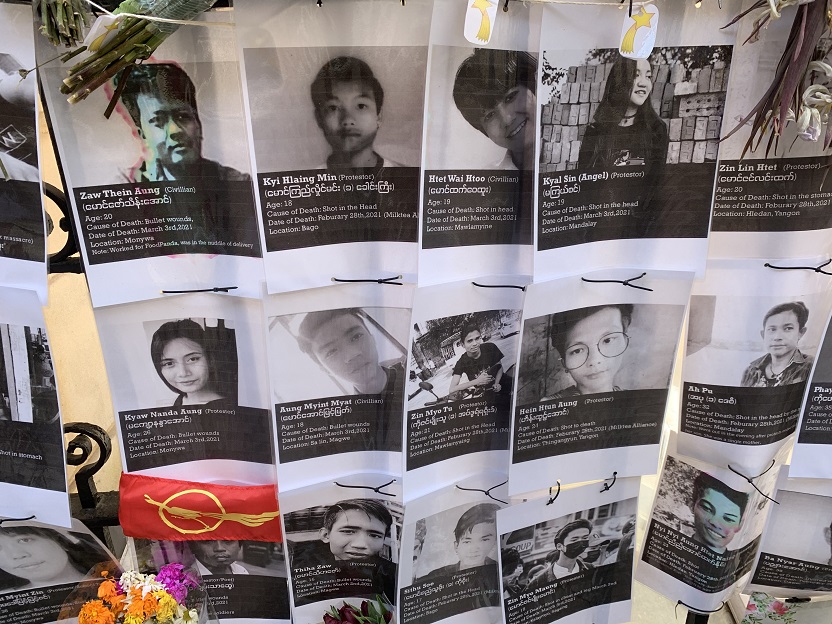

It’s the photos of young faces staring at you from the railings outside the Myanmar Embassy in London, that somehow bring the numbers to life, or death in their case as they no longer occupy this earth. The photographs remind you that they were someone’s son or daughter, perhaps someone’s brother, sister or grandchild. “All we wanted”, the faces appeal to you, “is what you have in Britain or our neighbours in India; freedom and democracy. Was that too much to ask for? The army, which was there to protect us, instead shot us in the head and chest, and now we are no more.”

The army, called Tatmadaw, is led by a mafia group of generals, interested only in protecting their wealth and influence with no regard to the interests of the citizens. It was when the results of the general election last November returned Aung San Suu Kyi, the de facto leader of Myanmar, and her government to power with a huge majority, the generals saw their position threatened and seized power in a coup. Encouraged by the example of Donald Trump just five days earlier, the generals claimed without any evidence that there had been massive voter fraud, which nobody believed, and arrested Suu Kyi and other leaders.

The coup incited huge street protests involving hundreds of thousands of Burmese which, after showing no abatement after several weeks, resulted in the generals initiating a reign of terror. Anyone seen to be opposing the coup was beaten and arrested, jailed and tortured. At night, shouting soldiers entered residential areas, conducted house-to house searches and indiscriminately fired live rounds into buildings. Local activists claim that the Tatmadaw is even charging families 120,000 kyat ($85) just to retrieve the bodies of their loved ones.

The Tatmadaw is the most resilient institution in Myanmar. Soldiers and their families live in cantonments, separated from the rest of society. They are indoctrinated into believing that the Tatmadaw is essential to the survival of the country. For its part, the military shows no signs of backing down, having intimidated its members into believing in their own privileged status in Myanmar’s society. The Tatmadaw’s historically strong internal discipline makes a split within its ranks extremely unlikely. Even if a soldier wanted to defect, sickened by the slaughter they are ordered to carry out, doing so would provoke reprisals against their families. Because of this, the generals can afford to suffer large casualties and thanks to their mafia-like involvement in the trafficking of Myanmar’s abundant natural resources, can probably weather the failure of the formal economy.

It’s the dramatic collapse of the economy which is yet another tragedy of the coup. Having averaged a growth rate of more than 6% per annum over the past ten years, more than doubling the gross domestic product, the Myanmar economy is now projected by the World Bank to shrink at least 10% in 2021. Some analysts are expecting things to get even worse. Fitch Solutions, the London-based analytics and financial intelligence group, is projecting a “conservative” 20% contraction for the 2020/21 fiscal year, adding that “there is no worst-case scenario on the economy that we can rule out”. The World Bank’s chief economist for Asia, said in a recent interview, “this contraction in growth for a small country seems to me disaster enough already. When you add to it all the other costs which have an impact on long-term growth, Myanmar has a dismal future.” Many would go much further, predicting a total collapse of the economy.

Perhaps the most alarming feature of the coup, however, is not the collapse of the economy, or the bloodshed resulting from the general’s failure to anticipate the resilience of the protestors, but the opportunities made available by the coup to the plethora of armed ethnic groups around the country. According to the International Crisis Group, an estimated one-third of Myanmar’s territory, mostly the border regions, is currently controlled by some 20 armed rebel outfits. Two of the most powerful armed groups, the Kachin Independence Army and the Karen National Union, have attacked Tatmadaw outposts multiple times in recent weeks. Another group, the Arakan Army, a hard-line Buddhist militia active in western Rakhine state, has vowed to “fight for their freedom from oppression”. The biggest ethnic army, the 30,000-strong United Wa State Army, which controls territory in the northeast and is also believed to be one of the biggest drug trafficking organisations in the world, has declared that it will use the coup to consolidate and expand the territory it controls. By some estimates, the ethnic armies have a total of 75,000 soldiers under their command. Although this is only about a third of the size of the Tatmadaw’s 350,000, it is still a sizeable number, sufficient to cause the generals a headache. As protestors in cities and towns begin to adopt more violent tactics, there is the real prospect of urban armed resistance or even guerrilla warfare. There are reports that some protestors have already met with members of ethnic militias to learn their tactics.

With fighting stretching across the country, many experts are alarmingly pointing to the example of the dictator Basher al-Assad and his allies in the failed-state of Syria. Last month was the 10th anniversary of the Syrian uprising, and just as al-Assad discovered all that time ago, the mafia generals of the Tatmadaw may realise that they are in too deep to waver from their current course, even if that means destroying their country in order to save themselves.

Neighbouring countries, such as India, will feel the pressure once again to accept droves of migrants and refugees and reckon with growing lawlessness, violence and desperation along their porous borders with Myanmar. With the economy devastated, the financial system collapsing and food prices rocketing, an untold number of people will fall into hunger and poverty. This has already evoked a strong emotional response in India’s north-eastern states between the ethnic groups which straddle the border. Myanmar’s Chins share kinship ties with the Mizos of Mizoram and the Kuki-Zomi group in Manipur. The Nagas people live on both sides of the Indo-Myanmar line, with many villages even sitting astride the border. The plight of their ethnic kin has triggered sympathy among the communities, with many organisations in Nagaland and Manipur expressing their solidarity with Myanmar’s protestors. They are already preparing to accept tens of thousands of refugees.

Myanmar’s history over the past fifty years reveals little hope for the early recovery of either democracy or the economy. Mutual alienation is worsening by the day. The mafia generals are isolated and consumed by a combination of greed, ignorance, fear and ambition, probably surprised by the sustained opposition and resistance they have provoked. The impact of the current coup will be even more severe than those of the past, with the generals impervious to reason and persuasion. Myanmar stands at the brink of state failure, civil war and collapse, a blood-drenched and tormented country sliding into an abyss.

India will soon have “Asia’s Syria” on its doorstep. A distressing prospect indeed.

John Dobson is a former British diplomat, who also worked in UK Prime Minister John Major’s office between 1995 and 1998.